Posted: September 6, 2024 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Food |

On 5 September 2024, Advocate General (AG) Capeta rendered her opinion in the case initiated by Protéines France, Union Végétarienne, Beyond Meat and others against the French state, disputing a French national Decree limiting the use of meaty names for meat replacements. This Decree dates back to 2022, implementing a specific article of the French Consumer Code. According to this article, the names used to designate foods of animal origin cannot be used to describe, market or promote foods containing vegetable proteins.

On 5 September 2024, Advocate General (AG) Capeta rendered her opinion in the case initiated by Protéines France, Union Végétarienne, Beyond Meat and others against the French state, disputing a French national Decree limiting the use of meaty names for meat replacements. This Decree dates back to 2022, implementing a specific article of the French Consumer Code. According to this article, the names used to designate foods of animal origin cannot be used to describe, market or promote foods containing vegetable proteins.

Two French Decrees

This Decree was immediately under fire by the same parties mentioned above before the French Council of State. According to them, the Decree was unlawful since, roughly speaking, the subject matter was fully harmonized at EU level by the Food Information to Consumers Regulation (FIC Regulation). The French Council of State then stayed the proceedings to ask four explanatory questions to the European Court of Justice (ECJ). Meanwhile, France repealed the 2022 Decree replacing it by a 2024 Decree, essentially similar to the previous one. The question then arose if the request for a preliminary ruling became devoid of purpose. The good news is that according to the AG this is not the case, essentially because the Council of State had informed the ECJ that the interpretation sought remained necessary to enable it to rule on the dispute in the mean proceedings.

System of 2024 Decree

The system of the 2024 Decree is twofold. First, it establishes a list of terms of the use of which is prohibited for the designation of foods containing vegetable proteins (examples: entrecôte, steak, jambon). Second, it authorizes the use of certain terms for the designation of foods of animal origin containing vegetable proteins, provided they do not exceed a certain proportion (examples: cordon bleu (maximum 3,5 % vegetable protein), merguez (maximum 2 % vegetable protein of which 1 % should consist of herbes), terrine de campagne (maximum 5 % of vegetable protein). Products legally manufactured or marketed in another Member State of the European Union or in a third country are not subject to the requirements of this Decree. French companies are however subject to a fine of € 7.500 if they act in violation thereof.

International context

These days, France is not the only Member State where naming issues of meat replacements arise. In fact, in several EU countries such as Italy, Poland and Romania, similar rules as in France have been adopted. Also outside the EU like in the US, in South-Africa and in Switzerland, similar legislative initiatives took place. At the same time, in countries like the Netherlands and in Germany, measures have been adopted expressly allowing the use of meaty names for non-meat products, specifically aiming to prevent any misleading of consumers. For example, in the Netherlands a product can be legally sold under the designation of “vegaschnitzel” (vegetarian Schnitzel) or “vegetarisch krabsalade” (vegetarian crab salad). So, it is about time to have a decision on this topic at European level. Should we be happy with the opinion of AG Cadeta? This most likely depends which side you are on. If you are a manufacturer of conventional meat products, this opinion will most likely meet your approval. If you are a food innovator, proposing alternatives to conventional meat, you will most likely be disappointed. This is why.

AG does not consider use of substitute products harmonized at EU level

The basic question in this debate is whether European legislation has specifically harmonized the naming of substitute products. According to the AG, this is not the case. As a consequence, this leaves room for Member States for establishing legal names, reserving those names for particular foods. Legal names should be distinguished from customary or descriptive names according to their intended effect. If the effect of national rules is that certain names are reserved for certain types of products, then they qualify as legal names. By adopting national measures prohibiting the use of certain customary and descriptive names, including when they are accompanied by additional indications that the product at issue contains plant-based, instead of meat-based, proteins, a Member State turns those customary and descriptive names into legal names. This is precisely the effect of the 2024 Decree and Member States are entitled to do so. The AG goes on to reason that the FIC Regulation does not preclude Member States from adopting national measures according to which meat replacement products can only have a maximum of vegetable proteins when using meaty names. Relevant here is that a distinction is made between domestic production and production abroad. In fact, the 2024 Decree stipulates that its rules do not apply to any imported products. The AG therefore considers the France Decree a purely internal matter. Finally, national administrative penalties sanctioning this regime are not counter to the FIC Regulation.

FIC Regulation does provide for harmonization of replacement products

I do not dispute that Member States can establish legal names at national level; this follows indeed from the FIC Regulation. This may be suitable in the context that food is highly cultural – certain dishes are found in one Member State and not in the other. This is the cultural wealth of Europe, where you only need to travel a few hundred kilometers to find entirely different landscapes, languages and cultural habits. I have however troubles to digest the conclusion that because of the fact that Member States can establish legal names for their specific food products, the subject matter would not be specifically harmonized at EU level. In fact, the FIC Regulation specifically addresses the topic of replacement products in its Annex VI. According to the AG, the rule laid down therein covers the use of meaty names for plant-based substitute products. From the Tofutown decision she however draws the learning that the Annex VI rule only applies if the meaty name is not a legal name. The difference between that case and the present one is that the legal names prohibiting the use of dairy names for dairy replacement products were embodied in the COM Regulation. This is specific harmonization at EU level indeed. In my view, it is questionable if legal names at national level that were newly established for a specific goal (see below) should be attributed the same weight as legal names that have been around for long at EU level, also taking into account the consequences thereof. This is all the more so, now that legal names are usually not prohibited terms as in the 2024 Decree, but positively phrased (example: “The beef and veal sector shall cover the products in the following table: live animals of the domestic bovine species… meats of bovine animals… fats of bovine animals….” – see COM Regulation Annex I, Part XV).

Consequences if ECJ adopts opinion AG Cadeta

If the ECJ embraces this opinion in its decision, there is a good chance that the 2024 Decree will stay in effect and will be enforced in France. Therefore, France national manufacturers of meat substitutes will be very much limited in the designation of their products. As such, they will be put at disadvantage in comparison to manufacturers in countries without such limitative legislation. Furthermore, other Member States having similar legislation in place most likely will feel confirmed in their policy and also enforce these provisions in their home turf. Companies formulating innovative food products thereby get the short end of the bargain on an EU wide basis. And this is not how the internal market was meant.

Two basic principles of internal market under threat

Two starting principles of the internal market are the free circulation of goods and a high level of consumer protection. Allegedly, the rationale behind the French Decrees was consumer protection. The AG explicitly addresses this topic. She states that it does not matter if the French authorities intended to protect consumers or the meat industry, or whether the reason behind such rules is the protection of national gastronomical heritage. At first sight, such a neutral approach could possibly make sense. At second sight, I tend to disagree. In the first place, because experience in the Netherlands has shown that consumers are not misled if meaty names are used for meat replacements. While the Netherlands may be considered very progressive in this regard, it was already established by ProVeg research in 2022 that plant-based labels do not confuse consumers. Secondly, restrictive measures are not needed to protect a certain industry or cultural heritage, since substitute products are not meant to entirely replace conventional meat products. Instead, they offer additional choice to the consumer, who decides to eat less or no meat. This should by no means be a threat to the meat industry, but an increase of food options for consumers. Exactly the purpose of the internal market.

For the reasons set out above, I sincerely hope that the ECJ will not adopt the current opinion of AG Capeta.

Credits image: Vegconomist, 11 April 2024

Posted: August 27, 2024 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Food, novel food |

UK High Court quashes FSA decision on novelty of monk fruit decoctions

Introduction

In the EU, food business operators (FBOs) have the responsibility to ensure that the food they are marketing is not unsafe. Most of the food products do not require prior market authorization, novel foods being one of the exceptions to the rule. For novel foods market authorization is granted based on an extensive safety evaluation by EFSA. If an FBO is unsure if its product / ingredient falls within the scope of the EU Novel Food Regulation, it can submit a voluntary consultation to a Member State, where the FBO intends to first market its product. The Member State competent authority will review the data submitted to establish if a history of use before 1997 can be established. In the affirmative, the product will not be considered novel. Examples of products not considered novel include pea protein concentrate and the Chinese pepper Capsicum chinense.

This blogpost covers the 19 March 2024 decision of the UK High Court on the novelty of a monk fruit decoction evaluated during a national consultation. This procedure was initiated by Guilin GFS Monk Fruit Corporation (Guilin GFS) against a joint decision of the UK Food Standards Agency (FSA) and the Food Standards Scotland (FSS). Guilin GFS is a world leader producer and manufacturer of monk fruit decoctions, having a 50 % global market share. Monk fruit is a small sub-tropical melon originating from China. Monk fruit decoctions can be applied to a wide range of foods and drinks as a sweetener and is popular for its low-calorie profile.

This blogpost covers the 19 March 2024 decision of the UK High Court on the novelty of a monk fruit decoction evaluated during a national consultation. This procedure was initiated by Guilin GFS Monk Fruit Corporation (Guilin GFS) against a joint decision of the UK Food Standards Agency (FSA) and the Food Standards Scotland (FSS). Guilin GFS is a world leader producer and manufacturer of monk fruit decoctions, having a 50 % global market share. Monk fruit is a small sub-tropical melon originating from China. Monk fruit decoctions can be applied to a wide range of foods and drinks as a sweetener and is popular for its low-calorie profile.

Figure 1 monk fruit image taken from the movie shown at www.monkfruitcorp.com

Applicable test and EC Guidance

After Brexit, the United Kingdom has maintained the EU Novel Food Regulation. Therefore, this decision is also of relevance for EU Member States. Under this applicable framework, the relevant test is whether monk fruit decoctions were used for human consumption to a significant degree in the EU or in the UK prior to 1997 (so-called history of consumption or HoC test). To adduce proof of a HoC, guidance can be taken from the Commission Guidance on Consumption to a Significant Degree dating back to 1997 (EC Guidance). In this context, it is important to note that the EC Guidance itself recognizes the difficulties of proof of significant use by the passage of time. It explicitly states that the examples of use are by no means exhaustive.

Evidence adduced

To meet the test on a HoC, Guilin GFS had adduced substantive evidence, including the following.

- Certificates of origin re. the export of processed foods monk fruits from mainland China to the UK during the period of 1998 – 2000;

- Evidence from a qualitative study from 2018 comprising face to face interviews with 71 participants in the UK and the EU demonstrating that processed foods containing monk fruits were sold in the EU / UK prior to 1997;

- Evidence from over 1.000 questionnaires as part of a quantitative population sample study from 2020 in the UK amongst people from Chinese descent re. their purchases of processed monk fruit;

- A survey in UK / EU supermarkets re. the types of monk fruit products sold before 1998;

- Signed declarations from restaurant owners, FBOs and the London Chinatown Chinese Association attesting the sale and / or consumption of monk fruit decoctions in the UK / EU prior to 1997.

FSA and FFS decision and rationale

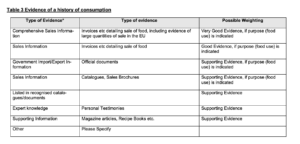

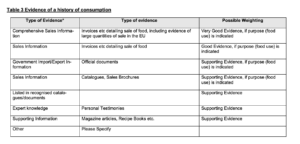

On 8 September 2022, FSA and FFS rendered the decision that Guilin GFS did not meet the HoC test (the Decision). FSA and FFS considered the evidence too small in samples and none of this evidence hit the box of “Very Good Evidence”. This is the type of evidence referred to in Table 3 to the EC Guidance reproduced below. The table at stake contains examples of evidence that might be adduced to meet the HoC test, such as invoices detailing the sale of the food product at stake, including evidence of large quantities of the sale in the EU (“Very Good Evidence”), mere invoices detailing the sale of the food at stake (“Good Evidence”) and magazine articles (“Supporting Evidence”). The main reason why FSA and FFS considered the evidence not up to standards was because invoices demonstrating sales of monk fruit decoctions prior to1997 were missing. Also, the FSA considered that personal testimonies were inherently incapable of demonstrating a significant HoC without verification of an independent source.

Figure 2: Table 3 to the EC Guidance on Consumption to a Significant Degree

Revision procedure and disclosure of FSA decision making process

Guilin GFS did not agree and initiated a revision procedure before the UK High Court on 2 December 2022, for which the hearing took place on 29 February 2024. The beauty of this procedure is that it provides full disclosure on all relevant documentation leading up to the Decision, including internal FSA correspondence conducted by its Novel Food policy advisors, as well as input from the FSA Social Sciences Team. This is an independent expert team, providing strategic advice to FSA. Contrary to the Novel Food FSA policy advisors, the Social Sciences Team considered the qualitative and the quantitative studies of Guilin to be reliable and robust. The Social Sciences Team did have a few verification requests to FSA’s Novel Food policy officers. However, according to Judge Calver, FSA’s Novel Food policy officers placed these questions out of statistic context to which they relate to validate the conclusion they reached earlier. Also, FSA’s Novel Food policy officers did not ask clarification questions to Guilin GFS when they reached their conclusion that monk fruit concoctions should be considered novel within the UK. Strikingly enough, they even reached this conclusion before the official validation of the dossier.

Debate during revision procedure

Guilin GFS opposed the Decision based on three legal grounds.

(1) It is incorrect that evidentiary requirements of the test for novelty under the Novel Food Regulation could not be met in the absence of pre-1997 sales invoices and data.

(2) It is incorrect that personal testimonies were categorically incapable to demonstrate a significant HoC unless verified by independent source.

(3) It is incorrect that it was necessary to demonstrate that monk fruit was consumed “exclusively for food uses”.

In reply, the Agencies served four witness statements from Novel Food policy advisors to “elucidate the reasons for the Decision.” Justice Calver states that based on the fact that these statements were made 15 months after the Decision, these need to be carefully scrutinized as there is a temptation to bolster and rationalize the Decision under challenge. Evidence that goes beyond elucidation and clarification is not permitted. When evaluating the witness statements, Justice Calver concludes the following.

Ad (1) The Agencies applied Table 3 to the EC Guidance too rigidly. Instead of considering “the whole picture” of evidence submitted by Guilin GFS, the Agencies saw that according to Table 3 the study results submitted by Guilin GFS did not qualify as “Very Good Evidence” or “Good Evidence”. They have then classified them as amounting “only” to “supporting evidence” “as defined in the Guidance”. This sentence makes clear that the Agencies consider anything other than invoices pre-1997 to be an inferior type of evidence as a category, amounting only to supporting evidence, which is not sufficient in itself to demonstrate a significant HoC.

Ad (2) The Agencies erroneously take the view that the evidence submitted by Guilin GFS’s should have been independently verified. There is no such requirement in the law or in the EC Guidance. Furthermore, the studies handed in by Guilin GFS had been qualified as reliable and robust by the Social Sciences Team. Also, with respect to personal testimonies, it is hard to conceive how these should be verified by third parties. As rightfully pointed out by Guilin GFS, such a requirement would frequently render personal testimonies redundant.

As a result, Judge Calver accepts grounds (1) and (2) and he considers the Decision flawed at these points. Moreover, he does not accept the four witness statements, as they try to re-write the reasoning in the Decision, which cannot stand with the wording of that document itself.

Ad (3) Finally, Judge Calver rules that the Agencies misapplied the relevant test when stating in the Decision that it was necessary to demonstrate that monk fruit was consumed “exclusively for food uses. The fact that the evidence submitted by Guilin GFS demonstrated a mixed use of monk fruit, in addition to food uses also including plant based medicinal products and even toothpaste, does not preclude establishing food use prior to 1997 in the EU or in the UK.

As a result, the claim for judicial review succeeds, the Decision is quashed, and the Agencies are ordered to re-consider the Claimant’s application in the light of this judgement. We can now see in the press that the Irish Food Safety Authority is reconsidering the novel food status of monk fruit extract and also the UK’s Food Standards Agency (FSA) has changed its stance regarding these products. The FSA now concludes that monk fruit concoctions are not a novel food, meaning that they can be used in food and beverages marketed in the UK. Reliable sources informed me that in the next weeks the Irish authorities – on behalf of the EU – are expected to issue a similar opinion to the UK.

Does this UK decision also apply for the EU?

In my opinion, this question should be answered positively. Rationale: according to the EC Guidance, an “established history of food use to a significant degree in at least one EU Member State is sufficient to exclude the food from the scope of Regulation (EU) 258/97.” The United Kingdom was an EU Member State during the period to which the evidence collected by Guilin GFS relates. The fact that Brexit occurred in 2020 does not change this. This also follows from the following statement in the EC Guidance: “The deadline 15 May 1997 is applicable to all Member States, irrespective from the date of accession to the EU.” By analogy, the same should apply in case of withdrawal of a Member State from the EU.

What can we learn from this decision?

In the first place, that it is a tough job to collect relevant evidence to establish a history of food use prior to 15 May 1997 in the EU (or the UK), especially since we are more and more moving away from this date. But it is doable. When looking at Guilin GFS, we can see that collecting product information, in combination with qualitative and quantitative data and affidavits can actually help to succeed in establishing such history of food use. Provided of course, you have a skilled lawyer at work to present your case. In the case at hand, the lawyers at work did an excellent job. One of these skilled lawyers is Brian Kelly, with whom I have been working together for more than 10 years now. Kudos to Brian!

Posted: July 25, 2024 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Advertising, alternative protein, Authors, Enforcement, Food, Information |

On 23 July 2024 a Dutch Court ruled in summary relief proceedings that Upfield cannot use the name “roombeter” for a plant-based alternative for butter, as this is in violation of the Regulation establishing a common organization of the markets for agricultural products (“COM Regulation”). You should know that “roombeter” translates in English as a composition of “cream” and “better”, whereas “cream” is a reserved designation under the COM Regulation that can only be used for dairy products. Furthermore, “beter” is close to “boter”, being the Dutch designation for butter.

On 23 July 2024 a Dutch Court ruled in summary relief proceedings that Upfield cannot use the name “roombeter” for a plant-based alternative for butter, as this is in violation of the Regulation establishing a common organization of the markets for agricultural products (“COM Regulation”). You should know that “roombeter” translates in English as a composition of “cream” and “better”, whereas “cream” is a reserved designation under the COM Regulation that can only be used for dairy products. Furthermore, “beter” is close to “boter”, being the Dutch designation for butter.

Facts of the case at hand

In the case at hand, Upfield markets a plant-based alternative for butter under the brand BLUE BAND and the product name ROOMBETER. The packaging of the product furthermore states “100 % plant-based alternative for butter” and “81 % less climate impact than butter”. The packaging itself consists of golden coloured paper that is also used for conventional butter in the Netherlands and it displays a curl of butter as shown below. The Dutch Dairy Association opposed the use of the product name ROOMBETER, as it is considered this a violation of the COM Regulation, as explained below.

Case before Dutch Advertisement Code Committee

Prior to this legal procedure , the Dutch Dairy Association had submitted a complaint regarding this product before the Dutch Advertisement Code Committee. This self-regulatory body ruled on March 21 last that the presentation of the product was misleading, since it could be understood to contain butter. The “e” in “beter” could be confused for an “o”, resulting in “boter”, which is Dutch for butter. And furthermore the golden coloured packaging added to the misleading character of the product. The topic of violation of the COM Regulation was left to civil law proceedings, as it exceeded the competence of the Committee.

Applicable legislation

Article 78.2 of the COM Regulation states that the definitions, designations and sales descriptions provided for in its Annex VII may be used in the Union only for the marketing of a product that conforms to the corresponding requirements laid down in that Annex. Annex VII contains, amongst other things, a product definition for milk and a list of milk products. It furthermore states that these designations may not be used for any other product than milk and milk products. The purpose of this provision is to protect dairy names from being used for non-dairy products.

Tofutown

You may recall that in its Tofutown decision back in 2017, the ECJ formulated a very strict prohibition of the use of diary names for non-dairy products (check out our blog on this case here). As a result of that prohibition, the use of the designation “Tofubutter” for a tofu-based product was in violation of the COM Regulation. As a general rule, the ECJ precluded the term ‘milk’ and the designations reserved by the COM Regulation exclusively for milk products from being used to designate a purely plant based product in marketing or advertising. This even applies if those terms are expanded upon by clarifying or descriptive terms indicating the plant origin of the product at issue

Arguments in favour of ROOMBETER

Upfield had argued it did not market its product under the designation ROOMBETER but under the designation BLUE BAND ROOMBETER. The brand BLUE BAND has been used for more than 100 years for margarine, so it is obvious for the consumer this is a plant-based product This is even strengthened by the Dutch translation of the designations “100 % plant-based alternative for butter” and “81 % less climate impact than butter”. So the name ROOMBETER does not designate, imply or suggest it is about a dairy product.

Court decision

The Court did not eat it. Instead, it very strictly applied the Tofutown doctrine, stating that a reserved designation under the COM Regulation cannot be used for a plant-based product. It went on to explain that if it is prohibited to use the designation “tofubutter” for a plant-based product, as it contains the reserved designation “butter”, for sure it is prohibited to use the designation “roombeter” for a plant-based product, as it contains another reserved designation under the COM Regulation. Also, the element “beter” (“better” in English) can hardly be perceived as a clarifying or descriptive term, as it does not refer (contrary to “tofu”) to a plant-based origin. In fact, its reference to plant-based origins can only be understood by those consumers who know the “skip the cow” ad or who further study the packaging of this product.

Upfield was therefore ordered to stop using the designation ROOMBETER within three months after the date of the legal decision.

Consequences of this decision

Should the conclusion of this decision be that any reference to dairy products should be meticulously avoided when marketing plant-based dairy replacements? This seems a very hard task, as manufacturers of these replacement products will want to indicate how their products can be used. Happily, this is not the case. It is still permitted to mention that your plant-based product is for instance a “yoghurt variation”, as this is perceived as a product explanation rather than a product designation. This is not in violation of the Tofutown doctrine and in line with a 2019 Dutch Supreme Court decision relating to a soy-based product marketed by Alpro. Advertising plant-based dairy alternatives nevertheless remains a delicate balancing act.

Posted: December 14, 2023 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Food |

Last month, the conference Regulating the Future of Foods took place in Barcelona, gathered more than hundred professionals active in the fields of precision fermentation and cellular agriculture. The purpose of the conference was to define hurdles and investigate opportunities in the current regulatory framework applicable to this sector. Many interesting presentations took place discussing the global perspective of our future food system and AXON moderated a workshop targeting tastings of cultivated foods, formulating a number of conversation topics. In this blogpost, we share the outcome of the discussions that took place during this workshop.

Last month, the conference Regulating the Future of Foods took place in Barcelona, gathered more than hundred professionals active in the fields of precision fermentation and cellular agriculture. The purpose of the conference was to define hurdles and investigate opportunities in the current regulatory framework applicable to this sector. Many interesting presentations took place discussing the global perspective of our future food system and AXON moderated a workshop targeting tastings of cultivated foods, formulating a number of conversation topics. In this blogpost, we share the outcome of the discussions that took place during this workshop.

Regulatory frameworks for tastings

Tastings of these products already took place, for instance in Israel. So far however only two countries have developed a legal framework for this purpose, notably Singapore and the Netherlands. In the tastings workshop, the procedure and the data requirements for setting up tastings in these countries have been explained, as you can see in the powerpoint inserted below. Furthermore, the following items were discussed.

1. Should the SGP / NL template become the blueprint for tastings or rather do this under the radar?

As follows from the comparison of the regulatory frameworks in Singapore and the Netherlands, these hugely overlap. Therefore, the question arose if these frameworks should become the blueprint for tastings in other countries. Kind Earth.Tech rightfully pointed out that at the beginning of the cultivated meat industry 10 years ago, all tastings held were illegal. They were however important to demonstrate proof of principle and to create appetite for further research. At the current state of the industry, all participants in the workshop however favoured a framework for tastings. Especially for start-ups, a tastings framework is valuable for showing both press and investors what they are up to. Furthermore, the Dutch initiative is useful to convince other EU Member States to develop similar initiatives. Bluu Seafood pointed out that Germany in particular was pretty shy to do so, as it considered tastings not to be in compliance with the EU Novel Food Regulation. Now German start-ups can point to the Dutch framework and request their authorities to take such initiative.

Another reason why tastings might be useful, is that the regulatory process takes a substantial amount of time. In Singapore, predicted timelines for Novel Food approval are between 9 – 12 months, but in reality, these go up. In fact, we have not seen any approvals for cell-based meat products since those for Good Meat and Upside Foods in Q4 2020. In the EU, the theoretic term for Novel Food approvals is about 18 months, but we know from practice it is more realistic to count 2 – 3 years. For the new industries of cellular agriculture, it remains to be seen if this term will apply as well. Demonstrating proof of principle during tastings can be a welcome deliverable before the final go.

Both in Singapore and the Netherlands, tastings should be done in a confined area, not open to the general public. This was understood by all participants in the workshop. At the same time, the concern was expressed that tastings should not become too clinical. They are meant to enjoy food products after all, not to evaluate medicinal products. Provided that a confined area and a selected audience can guaranteed, they can also be set up in a restaurant. Organising tastings during regular opening hours of restaurants will not yet be feasible, as such would fall within the scope of “placing on the market” under article 3.8 of the EU General Food Law Regulation. And placing on the market of Novel Foods requires pre-market approval.

2. For those previously involved in tastings: are they worth the efforts and did they bring you the data you were looking for?

The parameters set in the regulatory tasting frameworks are meant to be high enough to ensure food security but not dissuasive for companies to demonstrate safety prior to obtaining market authorization. Nevertheless, it takes considerable efforts to accommodate these parameters. For instance, producing useful microbiology data requires a minimum quantity of the product to be produced, which at this stage is still very expensive.

Obviously, the tastings themselves require substantial product input, often in combination with various non-cultivated carriers creating a hybrid product. This requires investments which for start-up companies can be challenging.

However, tastings have proved most valuable to collect input from chefs who will be working with cultivated products and to provide proof of principle to investors. In particular, repeating tastings with the same chefs offers the advantage that they can monitor and comment progress made and provide suggestions for further improvement, especially to accommodate the local palette.

2. Is the available guidance from the regulators sufficiently clear to decide how to set up the tasting and establish the safety of your product? Has the regulator been helpful in clarifying any company queries?

Companies that already conducted tastings in Singapore considered the Singapore Food Authority (SFA) to be helpful in not only overseeing this process, but also in facilitating it. Where a first tasting takes quite some work in setting up safety documentation and addressing any potential concerns of the regulator, repeated tastings proved to require much less preparations. This is particularly true if all tastings take place at the same location, as it facilitates the medical contingency plan. This requires the indication how much time it takes to reach a medical centre if any problems occur.

Most importantly, permission for tastings being granted is perceived as a quiet vote of confidence by the regulator, as it seems to have a minimum level of comfort with the safety of the product to be tasted.

3. Do you see any value in tastings to be set up at an EU level as opposed to national level only?

No, not really. It is important to create a product that appeals locally, and this may differ from community to community. Also, it was discussed that tastings organized at a central level could induce companies to rely on the greatest common denominator, i.e. a burger. This would in fact be a pity, as cultivated foods offer so much more opportunities than that. This was for instance demonstrated by Vow Foods who made a crème brûlée with its cultivated quail.

4. Any ideas what could be done to prevent that tastings slow down regulatory approvals?

The representative from SFA explained that the total staff available for the safety assessment of Novel Food AND the evaluation of an exemption for the tasting and sensory evaluation of Novel Foods is four to five persons. It is easy to understand that the more time is spent on the evaluation of tastings, the less time can be spent on the safety assessment of Novel Foods as such.

It was discussed that if tastings go wrong, for instance by creating a health problem, they imply a risk, not only for the product at stake, but also for the sector. On the other hand, tastings also spark enthusiasm, as was demonstrated by Solar Foods who even held tastings after obtaining market approval in Singapore.

So the communis opinion was that tastings should be dosed. Do not overdo it, but carefully weigh the advantage it can bring your company at a particular moment of its lifetime, for example during a funding round.

5. Do tastings qualify as studies under the EU Transparency Regulation, that should be notified to EFSA during an application for authorization of a Novel Food?

The EFSA representative present in Barcelona was quite outspoken regarding this question. If you have any concerns about toxicity or any other possible hazard, you do not want to expose your intended audience for tastings to such hazard. A tasting session is not a study. So no, tastings as such do not have to be notified to EFSA under the Transparency Regulation.

What’s next?

In the Netherlands, the CAN Expert Committee is expected to be nominated early 2024 and local companies are already gearing up for organizing tastings in situ. So soon the Dutch will continue to work on their Dutch dream. Watch that space!

Posted: October 23, 2023 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Food, New Genomic Techniques, organic |

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) do not generally receive a warm welcome from the average EU citizen. Possibly this is a case of ‘unknown makes unloved’. But GMOs can also bring positive things, for example, in the field of plant breeding. This summer, the European Commission published a proposal for an NGT Regulation. What exactly does this proposal entail and what are the expected consequences in practice? And how was this proposal received by the European Parliament in its draft report of 16 October last in the first reading of the legislative procedure?

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) do not generally receive a warm welcome from the average EU citizen. Possibly this is a case of ‘unknown makes unloved’. But GMOs can also bring positive things, for example, in the field of plant breeding. This summer, the European Commission published a proposal for an NGT Regulation. What exactly does this proposal entail and what are the expected consequences in practice? And how was this proposal received by the European Parliament in its draft report of 16 October last in the first reading of the legislative procedure?

Potential benefits GMOs and reluctance

GMOs can help develop plants that are more drought tolerant or less susceptible to certain fungi. This reduces the need for pesticides in cultivation, precisely one of the objectives of the EU Farm-to-Fork strategy that the Commission published at the beginning of its mandate in May 2020. At the same time, in the Netherlands the proposal for the NGT Regulation prompted Odin, Demeter, Ekoplaza and Greenpeace, among others, to start a petition calling for “Keep our food genetically modified free.” (in Dutch: Houd ons voedsel gentech vrij). At the time of writing this blogpost, the petition counts 47.709 signatories.

Scope of application NGT Regulation

The intended Regulation applies to NGT plants and to NGT products, meaning food and feed containing or consisting of or produced from NGT plants and other products containing or consisting of such plants. NGT plants are obtained from the following two genomic techniques or a combination thereof:

- Targeted mutagenesis: this is a technique that results in changes to the DNA sequence at precise locations in an organism’s genome;

- Cisgenesis: this is a technique that results in the insertion, into the genome of an organism, of genetic material already present in the total genetic information of that organism or another taxonomic species with which it can be crossed.

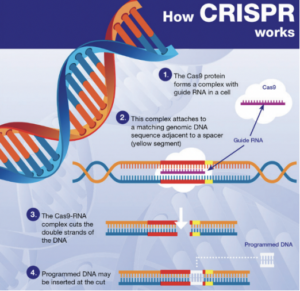

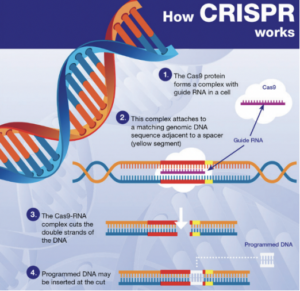

In essence, NGTs are genomic techniques such as CRISPR-Cas9. These techniques result in more targeted genomic modifications than older genomic techniques, which often involve the introduction of heterologous genetic material. The European Commission therefore recognizes that any risks associated with the use of NGTs are lower than those associated with older genetic techniques. This is what the risk assessment in the draft Regulation specifically addresses.

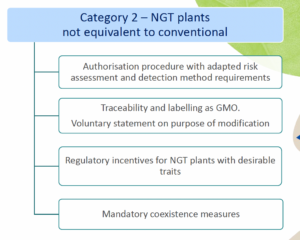

Two specific regulatory regimes for category 1 and category 2 NGT plants

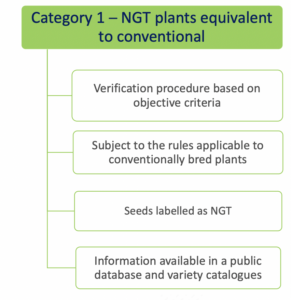

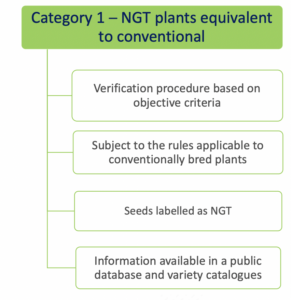

- Category 1 NGT plants: these plants are considered equivalent to conventionally bred plants based on the criteria in Annex I

of the NGT Regulation and as such do not need to undergo complete GMO risk assessment. Instead, a notification to a national GMO authority or to EFSA is sufficient;

of the NGT Regulation and as such do not need to undergo complete GMO risk assessment. Instead, a notification to a national GMO authority or to EFSA is sufficient;

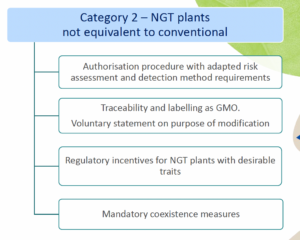

- Category 2 NGT plants: these plants are considered as GMOs and as such are subject to the GMO rules for authorization, traceability and labeling, however according to a modified system of more targeted risk analysis.

In addition to NGT plants, these regulations also apply to NGT products: that includes foods with ingredients made from such plants. This is why this proposed Regulation is so relevant for innovative food business operators.

In addition to NGT plants, these regulations also apply to NGT products: that includes foods with ingredients made from such plants. This is why this proposed Regulation is so relevant for innovative food business operators.

As mentioned above, for category 1 NGT plants, a notification procedure takes place and for category 2 NGT plants a full swing risk assessment. Both procedures involve a substantive assessment of whether plant material produced using targeted genetic techniques complies with the specifically developed rules for risk assessment. It is expected that the procedure for category 1 NGT products can be completed within a year, while the permit process for category 2 NGT foods is actually identical to that for regular GMOs. An innovation is that the NGT Regulation provides certain incentives for specific category 2 NGT foods that should speed up or simplify the assessment process.

Transparency regarding genetic engineering

Producers of organic products and advocacy organizations are concerned that, based on the NGT Regulation, genetically engineered food is walking into stores undetected. But is this concern justified? Based on the current text of this Regulation, both category 2 and even category 1 NGT products are excluded from organic production. Indeed, in the consultation process leading up to the NGT Regulation, the freedom of choice of consumers to buy food containing or not containing GMOs appeared to be an important issue. At the same time, the European Parliament considers the prohibition for organic farmers to use conventional-like category 1 NGT’s neither science-based, nor politically justifiable. It therefore calls in its draft report to create a fair level playing field and to only ban category 2 NGT plant material from organic production.

Category 1 NGT products listed in public database?

Whether or not allowed in organic production, there is no specific labeling requirement for Category 1 NGT products (Q 11 from EC Q&A). However, plant material with Category 1 NGT status must be included in a public database, expected to be similar to the Novel Food consultation database. In the Commisson’s proposal, plant reproduction material with Category 1 NGT status must additionally be labeled as such, with the identification number of the plant from which it is derived. At the level of production, this would provide an extra safeguard for distinguishing between conventionally grown crops and crops in which genetic engineering has been used. The European Parliament is however critical about this additional requirement in its draft report. It considers such discriminatory since category 1 NGT plants are conventional-like. According to the European Parliament, transparency and consumer choice are sufficiently ensured by disclosure in a public database. Therefore, even if the modifications proposed by the European Parliament will stand, there is no reason to believe that foods produced using CRISPR-Cas9 could go completely unnoticed.

Conclusion

With current changes in climate and constraints on available agricultural land with a growing world population, plant harvests will come under increasing pressure. NGTs are expected to meet the need to better equip plants for such challenges. The proposed NGT Regulation aims to simplify and thereby accelerate market access for such technology. For category 1 NGT products, except for a few open ends, this premise seems feasible in practice. A huge improvement with respect to current legislation is that the nature of the genetic change is decisive for risk evaluation, not the technique by which it is produced (product-based vs. process-based approach). For category 2 NGT products, market access is not expected to become much simpler based on the current proposal. Nevertheless, this proposal looks hopeful for plant innovations and thus for our food products of tomorrow. Also, there seems to be sufficient transparency to distinguish between crops produced with and without genetic engineering. My very bald hope would be that based on positive experiences with this regulation, the scope of this regulation will be extended to other fields, such as cellular agriculture and/or fermentation-based products. We will continue to follow closely how this legislation will develop.

Source images

- How CRISPR works: EU Parliament briefing on Plants produced by new genomic techniques

- Category 1 NGT plants: PPT DG Santé on Farm to Fork Strategy presented during EFFL Conference on 19 October 2023.

- Category 2 NGT plants: idem (2)

Thanks to my colleagues Jasmin Buijs and Max Baltussen for their valuable feed-back.

Posted: June 21, 2023 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Food, novel food |

On May 25, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled in a dispute arising between two manufacturers of food supplements. This is the first decision on the interpretation of the current Novel Food Regulation (applicable since Jan. 1, 2018). The dispute concerned the method of production of the functional ingredient spermidine. The dispute was hoped to clarify the question of what exactly a “new production process” under the Novel Food Regulation entails. The decision follows a request from a court in Austria, where this answer was needed to resolve a national dispute. This answer is also relevant to other countries, as the Novel Food Regulation applies EU-wide.

On May 25, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled in a dispute arising between two manufacturers of food supplements. This is the first decision on the interpretation of the current Novel Food Regulation (applicable since Jan. 1, 2018). The dispute concerned the method of production of the functional ingredient spermidine. The dispute was hoped to clarify the question of what exactly a “new production process” under the Novel Food Regulation entails. The decision follows a request from a court in Austria, where this answer was needed to resolve a national dispute. This answer is also relevant to other countries, as the Novel Food Regulation applies EU-wide.

Why do people consume spermidine?

Spermidine supplementation takes place with a view to supporting cellular autophagy, or cell renewal. This could promote the prevention of cardiovascular disease, prevent food allergies, and control the symptoms of diabetes. It has even been suggested that spermidine could extend human lifespan by 5 to 7 years. So says Advocate General (A-G) Campos Sánchez-Bordona in his opinion on the case dated Jan. 19 this year, citing various scientific sources (see footnotes 12 and 13 of this opinion). The A-G is an important advisor to the ECJ, which generally follows his or her opinions.

Background to this dispute.

The dispute in Austria was brought by The Longevitiy Labs (TLL), which markets the spermidine supplement spermidineLIFE. TLL extracts spermidine from ungerminated wheat germs through a complex and expensive chemical process. TTL applied for and obtained an EU Novel Food authorization for this food product (see Union List, entry “spermidine-rich wheat germ extract“). Then competitor Optimize Health Solutions enters the market with its own spermidine supplement. This is produced using a much simpler and therefore cheaper production process based on hydroponic cultivation of buckwheat seeds in an aqueous solution with synthetic spermidine. After harvesting the seedlings are washed in water, dried and milled to obtain flour. TLL believes that Optimize Health also needs a Novel Food authorization to market its product. It instituted proceedings seeking an injunction against further marketing of Optimize Health’s product without such an authorization.

Optimize Health argues it does not need a Novel Food authorization, because its product is not covered by the Novel Food Regulation. It is a fully dried traditional food obtained without any selective novel extraction method. Furthermore, it states spermidine has been available in food supplements in the EU market for more than 25 years. The germination of the buckwheat seeds of which its product is made would be a primary production process, to which the EU Hygiene Regulation applies, not the Novel Food Regulation. Furthermore, the Novel Food Regulation does not apply because its product involves “plants prior to harvesting” and these do not count as food under the EU General Food Law Regulation. The Austrian court decided that clarification of European law was needed to resolve this dispute and referred five questions to the ECJ.

Questions from the Austrian referring court

National judges who refer questions to the ECJ usually go for as many anchors as possible and thinking three steps ahead. If a possible answer by the ECJ to one question leads to a follow-up question by the inquiring national court, that follow-up question will be submitted upfront as well. The downside of this system is that if answering the first question is the end of the matter, answering the remaining questions is no longer needed. That is what we call procedural economy. In summary, the referring Austrian court asks the following questions:

- Should a food consisting of flour from buckwheat seeds with a high spermidine content be qualified as Novel Food in the category “foods isolated from (parts of) plants?”

- If not, might it be a Novel Food because a new production process has been used and does that term include primary production processes?

- If it is a novel production process, does it matter whether that process was not applied at all or only not applied to spermidine?

- If primary production processes are not covered by the term “new production process”, is it correct that the process of germinating buckwheat seeds in a nutrient solution containing spermidine is not covered by the Novel Food Regulation because it does not apply to plants prior to harvesting?

- Does it make a difference whether the nutrient solution contains natural or synthetic spermidine?

Decision of the ECJ

The ECJ answers question 1 – be it with some reservation – in the affirmative. Optimize Health’s product is a Novel Food because there is no evidence that this product was used for human consumption to any significant degree within the EU before 1997. This short answer is somewhat disappointing, as it makes answering the remaining questions irrelevant. Still, the ECJ does share two interesting considerations regarding the current Novel Food Regulation. It points out that the concept of “history of safe use within the Union” is not defined with respect to Novel Foods that must undergo the full authorization process. However, it is defined with respect to traditional foods from third countries. These are products that have been used as food outside the EU for considerable time, such as chia seeds. These products are subject to the requirement that the safety of the food has been confirmed by compositional data and experience of continued use for at least 25 years in the usual diet of a significant number of people in at least one third country. The ECJ finds that this requirement must be applied by analogy to the spermidine in question and concludes that said data have not been provided.

Propagation methods vs. complete production process

Another consideration of the ECJ concerns the Novel Food category of “food isolated from (parts of) plants”. An exception applies to products made by non-traditional propagation methods, which do not result in significant changes in the composition or structure of the food in question. The ECJ ruled that a distinction must be made between:

(1) propagation processes of which the purpose is to produce new plants; and

(2) processes involving the entire production process of a food product.

The process applied to Optimize Health’s product to achieve a high spermidine content falls into the second category. In other words, a manufacturing technique to enrich a product is not the same as a propagation technique. The ECJ instructs the Austrian court to take this into account when deciding the case at the national level. This reduces the likelihood that the exception to the Novel Food category above will apply and puts the ECJ’s reservation into perspective. Good chance, therefore, that the Austrian national court will indeed determine that Optimize Health’s product is a Novel Food.

New production procedure according to the A-G

With the above answer, the question of the Austrian court has been answered and the ECJ does not get to the remaining four questions. It is of course unfortunate that we will not know the ECJ’s decision on this. Therefore, it is interesting to see how the A-G ruled on this. Well: according to the A-G, enriching buckwheat seeds with spermidine should be considered a new production process. He argues that bio-enrichment with spermidine changes the composition and nutritional value of the buckwheat seeds flour. Indeed, its spermidine content becomes 106 times higher than that of un-enriched buckwheat seeds. The A-G cites studies according to which a higher spermidine content may be beneficial to health, but which also indicate that too high an amount of spermidine could be harmful to cells.

The A-G therefore concludes that prior authorization of Optimize Health’s product is indispensable to ensure food safety and avoid risks to consumers. He also refers to products such as selenium-enriched mushrooms and mushrooms treated with ultraviolet light after harvest to increase their vitamin D2 content, where such authorization has also taken place. Furthermore, the A-G argues that the effects and thus the safety of a new production process should be assessed in each individual case and thus not in general. The same production process may affect one foodstuff differently from another.

Conclusion

This spermidine case clarifies the criterion that should be applied to determine whether a food has a history of safe use in the EU and thus qualifies or not as Novel Food. By the way, this is not entirely new – there has already been a guidance document from the European Commission “Human Consumption to a Significant Degree” since 1997 that argues essentially the same thing. However, when this judgment is considered in conjunction with the A-G’s opinion, it does provide relevant new information for determining how to establish whether there is a new production process.

This is the case if it is established that an applied process significantly alters the composition and nutritional value of a foodstuff compared to a foodstuff to which such a process has not been applied. Thus, in such a case, a food must obtain authorization under the Novel Food Regulation. The A-G recognizes that the question whether it is relevant if the production process has been previously applied to any foodstuff (rather than to the foodstuff specifically) cannot simply be answered based on the legal text. So that requires interpretation of the specific article of the Novel Food Regulation on new production processes in the light of its context and purpose. For now, we do not yet know whether the ECJ supports his interpretation. Hopefully we will find out in another case. It does sound plausible to me.

Posted: October 31, 2022 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, clean meat, cultivated meat, Food, novel food |

This blogpost covers the recent GFI report European messaging for cultivated meat (GFI Report) as recently presented during the International Scientific Conference on Cultivated Meat (ISCCM).The further aim is providing the relevant regulatory context. Market authorisation is often mentioned as the delaying factor for market access of cellular agriculture-based products. If you are interested to know how the names and narratives by which these products are designated fit into the EU regulatory framework, read on!

This blogpost covers the recent GFI report European messaging for cultivated meat (GFI Report) as recently presented during the International Scientific Conference on Cultivated Meat (ISCCM).The further aim is providing the relevant regulatory context. Market authorisation is often mentioned as the delaying factor for market access of cellular agriculture-based products. If you are interested to know how the names and narratives by which these products are designated fit into the EU regulatory framework, read on!

Accelerated developments in cultivated meat field

Developments in the field of cellular agriculture have been tremendous since the first market approval of Eat Just’s hybrid cultivated chicken product in Singapore at the end of 2020. To name just a few:

- September 2021: Singapore Food Authority grants CMO Esco Aster a license to manufacture cultivated meat for commercial production. Meanwhile, several cultivated meat companies have concluded partnerships with Esco Aster for production purposes.

- October 2021: US Dept. of Agriculture announces an award of USD 10 million to Tufts University to set up a National Institute for Cellular Agriculture;

- October 2021: The Israeli Innovation Authority announces to invest an amount equalling USD 69 to establish four new public-private consortia, including one targeting cultivated meat;

- November 2021: opening of Upside Food’s 53.000 square foot production facility for cultivated meat;

- April 2022: The Dutch government agrees to invest through its National Growth Funds an amount of € 60 million to boost the formation of an ecosystem around cellular agriculture, representing the largest public funding in this field globally so far;

- October 2022: Mosa Meat announces construction of its 77 square cultivated meat campus.

- Upcoming event in November 2022: FAO Expert consultation in Singapore for gathering scientific advice on cell-based food products and food safety considerations.

For a comprehensive overview of the developments in the cultivated meat market, reference is made to GFI’s 2021 State of the Industry Report on Cultivated Meat and Seafood. This report also points out that investments in cultivated meat companies have grown from USD 420 million in 2020 to USD 1,8 billion in 2021. The sector clearly grows in interest and substance.

Market authorisation: where to start?

Quite a few of the cellular agriculture companies have their origin in the EU and in the UK. During the latest editions of KET Conference, the New Food Conference and the ISCCM, I witnessed however that most of them intend obtaining market approval in Singapore first, then in the United States of America and only afterwards in the European Union. Why is that? And it is justified based on the current EU regulatory framework?

EU: attractive but very diverse market

The European Union represents a market of more than 440 million consumers and thereby is a bigger market than for example the United States, counting currently over 330 million inhabitants. Based on this headcount alone it makes sense for each serious food business operator to consider the EU market for the launch of a new product. At the same time, the European Union consists of 27 Member States having their own cultural and culinary habits. This is exactly what is pointed out in the GFI Report. These varied backgrounds mostly require dedicated product communication. To a certain extent, some overlap in effective product communication in the four countries in which the research took place, was found as well.

Product communication vs. marketing

For clarity, there is a thin line between marketing and product communication, especially for pre-commercial companies that need to raise funds to get their product to the market. This was recognized by David Kay from Upside Foods in his ProVeg presentation, which you can watch here (starting at 26th minute). For the time being all cultivated meat companies, except perhaps East Just, are pre-commercial companies. Product communication means providing factual understandable information to the targeted public. Marketing means the direct or indirect recommendation of goods, services and/or concepts by on behalf of an advertiser, whether or not using third parties. The purpose of the GFI report is to develop positive, persuasive nomenclature and messaging for cultivated meat for each language and cultural context. In my view, the report thereby operates somewhere in the middle between product communication and marketing.

Rationale for common denominator

As recently acknowledged by the FAO, internationally harmonized terms to designate cultivated meat would be helpful to facilitate understanding worldwide:

“Cell-based food products are also referred to as “cultured” or “cultivated” followed by the name of the commodity, such as meat, chicken or fish while the process can also be called “cellular agriculture”. Given the various terminology in use for this technology, internationally harmonized terms for the food products and production processes would facilitate understanding at global level.”

Overlap in product communication

Back to the research performed by GFI. The very reason for the GFI Report is the current lack of consensus within the sector on the best nomenclatures and narratives to use. Negative framing of cultivated meat (which in some EU countries is already a reality) could prevent consumer acceptance of these products. GFI therefore tested which names and narratives worked well in each of France, Italy, Spain and Germany. Regarding the name, the GFI Report establishes that terms that loosely translate to “cultivated meat” are understood in all these countries and have a positive rather than a negative connotation. This comes down to “viande cultivée” / “carne coltivata” / “carne cultivada” / “kultiviertes Fleisch” or “Kulturfleisch”. As to the accompanying narratives, overall findings are that communication on cultivated meat should not be too technical. For example, reference to “cells” and “bioreactors” should generally be avoided, whereas analogies construed with existing food practices, such as the brewing of beer, work well.

Particularities for France, Italy, Spain and Germany

The research however also showed diverging results in the countries involved, both as regards the familiarity and the appreciation of cultivated meat. In France for instance, the terms “cells” and “bioreactor” are considered too reminiscent of a laboratory and too far removed from the language of food. In Italy “bioreactor” is even considered reminiscent of nuclear energy. In Spain, the terms “cells” and “bioreactors” are considered too scientific. In Germany on the other hand, the reference to “cells” is interpreted in an entirely different way. In this country, stating that cultivated meat stems from animal cells is interpreted that it tastes like conventional meat. In view of the market potential, in France 33% of the respondents indicate they would buy this food, whereas in Germany, Italy and Spain, these percentages are 57%, 55% and 65% respectively.

Do we have any examples from practice?

In an interview broadcasted on French television BFM Business on 5 October 2022, Nicolas Morin-Forest (NMF) delivers a fairly inspiring message on the cultivated foie gras of Gourmey. Whereas the TV station consistently refers to “viande synthèse”, NMF speaks of “viande culture” and stresses this is not a plant-based product (“Ce n’est pas du végétal”). Instead, he states, Gourmey delivers real animal protein with the same quality as animal protein in terms of taste (“C’est de la vraie protéine animale avec toutes les qualités gustatives des proteines animales”). He also mentions that with this product, it is no longer necessary to conclude any compromises; it associates culinary delight with the so-called protein transition (“Plus de compromis: le plaisir est au centre de l’assiette; au centre aussi de la transition alimentaire”). He finally points out that France can play a fundamental role in this protein transition, specifically based on its culinary foodprint and gastronomic history (“La France a un rôle fondamentale à jouer par notre patrimoine culinaire, par notre histoire gastronomique”).

Why are names and narratives of relevance for market authorisation?

The four researched countries are all important EU Member States, both in terms of head count and political influence. Germany is very influential at EU level and has the largest population of any EU country. Spain is reported to have strong influence over EU policy as well and has the highest meat intake in the EU. Both France and Italy have significant influence over EU agricultural policy. However, these latter two are the countries where we have seen the most hostile approach to non-conventional meat. In France for instance, there is ongoing litigation before the Conseil d’Etat concerning the prohibition of meaty names for non-conventional and alternative meat products.

Legal basis EU authorisation procedure

The position taken by all four countries will be of relevance during the authorisation procedure of cultivated meat in the EU. Cultivated meat – if produced without genetic modification – is regulated under the EU Novel Food Regulation. Contrary to legislation in Singapore (of very recent date) and in the US (still to be further shaped), this Regulation has already been in place since 1997 and was updated in 2018. The system is ready to receive applications when the companies are ready, too. Extensive EFSA guidance on the preparation of a Novel Food application is available.

Dynamics at the PAFF Committee

After EFSA makes available its safety evaluation regarding an application for authorisation of a cultivated meat product, the European Commission submits a draft implementing act to the PAFF Committee. This committee consists of representatives of each Member State and subsequently provides by qualified majority (i) a positive opinion, (ii) a negative opinion or (iii) no opinion at all. “Qualified majority” here means that 55% of the Member States vote in favour, representing at least 65 % of the EU population. The dynamics of this decision making procedure have been described in detail in the article Meat 3.0 – How Cultured Meat is Making its Way to the Market, which also provides for a flow chart at the end. In case of a negative opinion, one of the options is to escalate to the so-called Appeal Committee. In case of a negative opinion of the Appeal Committee, the EC shall not render an implementing act. In plain language: the application for authorisation of the cultivated meat product at stake will in such case be rejected.

Conclusion

Based on the above, It is quite easy to make the calculation that if for instance the representatives in the PAFF Committee from Germany (over 80 million inhabitants) or France (over 65 million inhabitants) do not vote in favour of an application for authorisation of a cultivated meat product, it will be difficult to reach the 65% threshold. Agreement on the name of product, understanding of the technology behind it, as well as the various benefits it could bring is therefore expected to be key for the evaluation procedure by the PAFF Committee. When these products make it to the EU market, they will be subject to the applicable legislation on food information and marketing. Until that time, it is of the essence that comprehensive product information reaches the relevant stake holders. It follows from the GFI Report that chefs and dieticians are best placed to deliver this message. In turn, the cultivated meat companies are in the position to provide them with relevant information. I can only encourage them to do so, if only to expedite market access in the EU.

————————-

Additional useful sources linked to this topic are ProVeg’s reports Communicating about cultured meat and The role of imagery in consumer perceptions of cultured meat (the latter targeting the UK specifically), each published in October 20222 and to be downloaded here.

————————

Foto credit: BioTech Foods

Posted: January 26, 2022 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Advertising, Authors, Food |

How to strike the right balance between freedom of speech and preventing unfair advertising targeting the dairy industry? This is the object of a Q4 2021 decision of the Appeal Board of the Dutch Advertising Code Committee, consisting of an advertising campaign on bus shelters in the Netherlands and a website campaign. If you are interested to know how broad the scope of “advertising” is and how a rather aggressive campaign was evaluated, continue reading. This post will be limited to the bus shelter campaign only since that already demonstrates the operation of the applicable legal framework.

How to strike the right balance between freedom of speech and preventing unfair advertising targeting the dairy industry? This is the object of a Q4 2021 decision of the Appeal Board of the Dutch Advertising Code Committee, consisting of an advertising campaign on bus shelters in the Netherlands and a website campaign. If you are interested to know how broad the scope of “advertising” is and how a rather aggressive campaign was evaluated, continue reading. This post will be limited to the bus shelter campaign only since that already demonstrates the operation of the applicable legal framework.

Bus shelter campaign attacking dairy industry

The bus shelter campaign showed several very explicit pictures demonstrating the misery life of young calves. Under the title “Do you need help quitting?” information was provided on the consequences of the dairy industry for these calves. The text on the various posters in the bus shelters stated the question “Do you need help quitting?”, followed by the following texts:

- Poster 1: “ “Dairy causes serious animal suffering. Calves are taken away from their mothers immediately after birth.”

- Poster 2: “Dairy is deadly. On a yearly basis, 1.5 million calves are slaughtered for dairy”.

- Poster 3: “Milk destroys more than you like. Calves are being fed artificial milk because the cow’s milk ended up in your cappuccino.”

The wording used above appeals to two well-known anti-smoking and anti-alcohol campaigns in the Netherlands, notably “quit smoking” and “alcohol destroys more than you like (your marriage for example).” The driver behind the anti-diary campaign is the Dutch organisation Animal & Law (“Dier & Recht”) that claims to be voice of the animals. This campaign was opposed by the Dutch dairy organization DairyNL (“ZuivelNL”), that aims to strengthen the Dutch dairy chain in a way that respects the environment and society. DairyNL considered this campaign misleading and therefore unfair.

Scope of the Dutch Advertising Code

The Netherlands knows a system of a self-regulation for advertising, embodied in the Dutch Advertising Code. Companies and other organisations can choose to submit to this system and the outcome (so-called recommendations) of cases based on complaints by whoever considers an advertisement misleading has a high degree of compliance (97 % in 2020). Animal & Law argued that their campaign was out of scope, as it did not envisage selling any products or services. Instead, it alleged to be a non-profit organisation that by public campaigns aims to improve the (legal) position of animals. Alternatively, it argued that if their campaign was captured by the scope of the Dutch Advertising Code, it would benefit from the principle of freedom of expression, as protected by the European Convention on Human Rights. Animal & Law overlooked however that the Dutch Advertising Code also captures ideas that are systematically recommended by an advertiser. The anti-dairy campaign by Animal & Law was found to meet this test. The Advertising Code Committee (“Reclame Code Commissie”) subsequently assessed for each bus shelter poster whether the information constituted misleading advertising.

Test for misleading advertising

The test applied is as follows: Advertising is unfair if it contravenes with standards of professional conduct and if it substantially disrupts or may disrupt the economic behaviour of the average consumer. One could consider this is exactly what Animal & Law was after and for a good cause. Under the Dutch Advertising Code however, aggressive advertising is at any rate considered unfair. Furthermore, all advertising containing incorrect or ambiguous information regarding specific aspects of the product at stake is considered misleading, if such information entices or may entice the average consumer to take a transaction decision (including refraining therefrom) that such consumer otherwise would not have made.

Poster 1

Just below the text “Do you need help quitting?” a milk carton is shown depicting a young calf being led away in a wheelbarrow followed by the text “Dairy causes serious animal suffering. Calves are taken away from their mothers immediately after birth.” All of this is depicted within a black framework, just like the health warning on a box of cigarettes. DairyNL argued, amongst other things, that according to the Netherlands Nutrition Centre, the consumption of dairy fits into a healthy diet, whereas the reference to quitting creates the impression dairy is very bad for human health. During the hearing, Animal & Law acknowledged that it is incorrect to state in general that dairy is not healthy. The Advertising Code Committee therefore considered the information re the quitting provided on poster 1 to be ambiguous and thus misleading. This results in unfair advertising.

Poster 2

This poster shows the same setting as poster 1, namely a milk carton depicting an earmarked calf surrounded by a black framework. According to DairyNL, in this context the text “Dairy is deadly. On a yearly basis, 1.5 million calves are slaughtered for dairy” can only be understood as a health warning. Furthermore, the absolute claim on the number of slaughtered calves creates the impression that this slaughter can only be attributed to the dairy industry, whereas it also serves meat production. Animal & Law had responded that calves are merely a by-product of dairy. It had used the warning that “dairy is deadly” to awaken the conscience of consumer. Obviously, the consumer understands the calf is going to die, not the consumer. The Advertising Code Committee considered this warning to be misleading, for the same reason as mentioned above. This part of the advertising was therefore considered unfair. The complaint regarding the slaughter was strikingly not addressed. I deduce therefrom that at any rate it was not concurred with.

Poster 3

On this poster, a calf is shown behind the bars of its small cage. DairyNL argued the setting of this poster (identical as described above) and the text “Milk destroys more than you like” links milk to two health hazard products, i.e. cigarettes and alcohol. DairyNL also argued that the claim “Calves are being fed artificial milk because the cow’s milk ended up in your cappuccino” creates the impression calves only drink artificial milk. Animal & Law refuted this complaint by explaining the claim does not state that calves only drink artificial milk. Animal & Law did not deny calves are being fed colostrum right after birth. However, this only takes 2 days, whereas the natural weaning period of calves amounts to 6 – 12 months. Here the Advertising Code Committee did not consider DairyNL’s claim founded, as DairyNL did not dispute that after a few days, the calves are being fed artificial milk instead of cow’s milk.

Conclusion

So what is the result of all this and what can we learn from this advertising decision? If the campaign of Animal & Law was mainly after shock and awe, it certainly succeeded. The pictures of the calves shown in the context of health warnings for cigarettes did not miss their effect. Potentially, a number of consumers became aware of certain facts it did not realise before. But will these consumers say a definite no to dairy? That’s the question, as the campaign may also have a counterproductive effect. Personally, I expect the chances of a seductive dairy alternative much higher for inducing consumers to eat no more (or just less) dairy. The learning from this decision is that even if the freedom of expression is a major public good, it also has its limits. No purpose justifies providing incorrect or ambiguous information. This learning applies equally to those outlining the pro’s of dairy alternatives, but certainly also to those emphasizing the con’s of dairy.

Posted: October 25, 2021 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Enforcement, Food |

Over the last ten years, the trend of clean labelling in consumer food products has gained ever more ground. Clean labelling consists of replacing E numbers such as citric acid (E 330) and beetroot (E 162) by their natural counterparts, such as plant extracts. There is nothing wrong with E numbers per se. The use thereof is subject to specific purity criteria and their safety has been evaluated and approved. Consumers however tend to less appreciate E numbers as not being ‘natural’. This is not an unambiguous notion, as shown by this blogpost. Designing food products based on these consumer preferences can however become a tricky business, which was shown by a letter of the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport of 16 June this year as sent to the Dutch food industry associations. Even if this letter dates back to this Summer, it recently gained again traction on social media. We therefore consider it helpful to highlight the strict measures announced therein.