CBD as a food product: no drug, isn’t it? The interaction between food and opium legislation.

Posted: March 5, 2021 | Author: Jasmin Buijs | Filed under: Authors, cannabidiol, cannabis, Food | Comments Off on CBD as a food product: no drug, isn’t it? The interaction between food and opium legislation. A number of legal developments in the field of cannabidiol (CBD) took place in the last few months of the previous year. For example, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled in November that a member state cannot prohibit the marketing of CBD that was lawfully manufactured and marketed in another member state. Less than a month later, the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) voted on six recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) regarding the reclassification of cannabis in the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (Single Convention). In practice, there appears to be confusion about the meaning of these developments for CBD as a food product. This confusion seems to arise from the interaction between food and opium legislation, both of which are applicable to this product. This article aims to provide clarity on these latest developments.

A number of legal developments in the field of cannabidiol (CBD) took place in the last few months of the previous year. For example, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled in November that a member state cannot prohibit the marketing of CBD that was lawfully manufactured and marketed in another member state. Less than a month later, the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) voted on six recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) regarding the reclassification of cannabis in the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (Single Convention). In practice, there appears to be confusion about the meaning of these developments for CBD as a food product. This confusion seems to arise from the interaction between food and opium legislation, both of which are applicable to this product. This article aims to provide clarity on these latest developments.

CBD is not a narcotic according to the ECJ

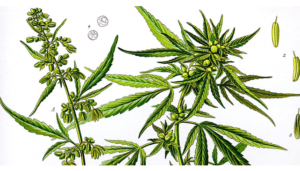

On 19 November 2020, the ECJ ruled, in summary, that the free movement of goods entails that when CBD is lawfully manufactured and marketed in one member state, it may, in principle, also be marketed in another member state. This is, however, different when Article 36 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) justifies an exception to the free movement of goods, such as for the protection of health and life of humans. Yet, the trade restricting or prohibiting measure must in such a case be appropriate for securing the attainment of the objective pursued (the protection of health and life of humans) and must not go beyond what is necessary in order to attain it. To reach the aforementioned conclusion, the preliminary question had to be answered whether CBD falls within the scope of the free movement of goods. This principle does namely not apply to narcotics, which are prohibited throughout the Union (with the exception of strictly controlled trade for use for medical and scientific purposes). Based on the Single Convention and the Convention on Psychotropic Substances, the ECJ reasoned that CBD is subject the free movement of goods. Both conventions codify internationally applicable control measures to ensure the availability of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances for medical and scientific purposes and to prevent them from entering illicit channels. The Convention on Psychotropic Substances regulates psychoactive substances, whether natural or synthetic, and natural products listed in the schedules to the Convention, including tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). CBD is not included. The Single Convention applies, inter alia, to cannabis (defined as “the flowering or fruiting tops of the cannabis plant (excluding the seeds and leaves when not accompanied by the tops) from which the resin has not been extracted, by whatever name they may be designated”). Although a literal interpretation of the above provision would lead to the conclusion that CBD (not obtained from the seeds and leaves of the cannabis plant) falls within the definition of cannabis, such an interpretation is not consistent with the purpose of the Single Convention, namely protecting the health and welfare of mankind. Indeed, according to the current state of scientific knowledge, CBD is not a psychoactive substance.

UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs reclassifies cannabis

Shortly after the ECJ ruling regarding, among others, the Single Convention, the CND put six WHO recommendations to vote on 2 December 2020. This voting session would have taken place earlier, though had been postponed so that the voting countries had more time to study the matter and to determine their position. The WHO recommendations dealt with the reclassification, removal and addition of cannabis (substances) in the various schedules (Schedule I, II, III and IV) to the Single Convention. These four schedules represent four categories of narcotics and each category has its own rules. The substances in Schedule VI are  controlled most strictly; they are considered dangerous without relevant medicinal applications. Schedule I concerns the second most strictly controlled category. The substances in this Schedule are subject to a level of control that prevents harm caused by their use while not hindering access and research and development for medical use. The lightest criteria apply to Schedule II and III. For example, Schedule II lists substances normally used for medicinal purposes and with a low risk of abuse.

controlled most strictly; they are considered dangerous without relevant medicinal applications. Schedule I concerns the second most strictly controlled category. The substances in this Schedule are subject to a level of control that prevents harm caused by their use while not hindering access and research and development for medical use. The lightest criteria apply to Schedule II and III. For example, Schedule II lists substances normally used for medicinal purposes and with a low risk of abuse.

Bedrocan (currently the sole supplier of medicinal cannabis to the Dutch government) has summarized these six WHO recommendations as follows:

- Extracts and tinctures are removed from Schedule I.

- THC (dronabinol) is added to Schedule I under the category Cannabis & Resin. Subsequently, THC is removed from Schedule II of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

- THC isomers are added to Schedule I under the category Cannabis & Resin. Subsequently, THC isomer is removed from the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

- Pure CBD and CBD preparations with maximum 0.2 % THC are not included in the international conventions on controlling drugs.

- If they comply with certain criteria, pharmaceutical preparations that contain delta-9-THC should be added to Schedule III, recognizing the unlikelihood of abuse and for which a number of exemptions apply.

- Cannabis and cannabis resin are removed from Schedule IV, the category reserved for the most dangerous substances.

In the end, only the recommendation to remove cannabis from Schedule IV (i.e., recommendation 6) was approved, on the grounds that there are also positive aspects to cannabis. However, this does not mean that cannabis can now be freely traded. Cannabis is still included in Schedule I and is therefore in principle a prohibited substance. Having said that, research and product development for medical purposes is permitted if a country so desires. In the Netherlands, the Dutch Opium Act already allowed for this under certain conditions. The reclassification of cannabis is therefore more symbolic in nature than that it brings about practical changes.

The recommendation to explicitly exclude CBD from the scope of the Single Convention has thus been rejected. The industry considers this a missed opportunity to clarify the (legal) status of CBD with traces of THC. This rejection was on the other hand in line with the viewpoint of the European Commission, which advised its member states that sit on the CND (i.e. Belgium, Germany, France, Hungary, Italy, Croatia, the Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Spain, Czech Republic and Sweden) to vote against this recommendation since more research would be needed. For example, the European Commission takes the position that the proposed THC limit of 0.2 % is not sufficiently supported by scientific evidence. The WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence (ECDD) notes in this regard that medicines without psychoactive effects that are produced as preparations from the cannabis plant will contain traces of THC and provides the example of the CBD preparation Epidiolex as approved for the treatment of childhood-onset epilepsy, which contains no more than 0.15 % THC by weight. At the same time, WHO ECDD recognizes that it may be difficult for some countries to conduct chemical analyses of THC with an accuracy of 0.15%. Hence, it recommends the limit of 0.2 % THC. This limit is already known to food companies from the so-called Novel Food Catalogue of the European Commission, which recalls that in the EU, the cultivation of Cannabis sativa L. varieties is permitted provided they are registered in the EU’s ‘Common Catalogue of Varieties of Agricultural Plant Species’ and the THC content does not exceed 0.2 % (w/w). This does, however, not necessarily mean that products derived from such cannabis varieties can be freely marketed as food.

CBD as food product

With respect to cannabis extracts such as CBD, as well as its synthetic equivalent, no history of safe use has been demonstrated. As a result, these products qualify as novel foods and can only be placed on the EU market after approval by the European Commission. Several food companies such as the Swiss company Cibdol AG, Chanelle McCoy CBD LTD from Ireland and the Czech CBDepot, have already applied for the required novel food authorization. However, the assessment of the relevant dossiers has been paused, presumably because it was still unclear whether CBD qualified as a psychotropic substance and narcotic. Such a qualification would exclude use as a foodstuff. Thanks to the ECJ ruling, this has now been clarified, on the basis of which the European Commission will likely resume the evaluation of the various applications for CBD as a novel food.

CBD under the Dutch Opium Act

A potential approval of CBD as a novel food does, however, not automatically mean that CBD can be sold in the EU without any (legal) obstacles. The Novel Food Catalogue makes this reservation explicit by indicating that specific national legislation, other than food legislation, may restrict the placing on the market of a cannabis product as a food. In practice, it will in particular come down to opium legislation.

Although the ECJ clarified that CBD is not a narcotic, it did not specify how pure CBD must be to fall outside the scope of the Single Convention and to be freely traded. The respective rejected WHO recommendation referred to a THC content of up to 0.2 %. In the Netherlands is, however, only a contamination level of < 0.05 % allowed. This impurity can be caused by traces of THC, but also by the presence of other cannabinoids. Only pure CBD, i.e. with a purity level of > 99.95 %, falls outside the scope of the Dutch Opium Act. Having said that, there is another catch: although the Dutch Opium Act does not cover CBD, this Act is applicable to the cannabis plant (or its parts) from which the CBD is extracted. The production of (natural) CBD can therefore not take place in the Netherlands.

Conclusion

Recent developments in the field of CBD have clarified that CBD is not a narcotic and therefore does not fall under the Single Convention. Food businesses are nevertheless warned to not yet start celebrating. If they want to market CBD as a food, they will still have to go through the novel food procedure, or market a product in accordance with the terms of an already approved CBD product. The latter is possible insofar data protection does not prevent this. Besides this, the purity level of CBD is decisive to stay away from opium legislation. There is still no international agreement on what this level should be. Food businesses operating in different member states are therefore advised to seek local advice when marketing CBD in the EU.

Active disclosure of inspection results: how to prevent naming & shaming?

Posted: October 2, 2020 | Author: Jasmin Buijs | Filed under: Authors, cannabidiol, cannabis, Disclosure of information, Enforcement, Food, Food Supplements, Health claims | Comments Off on Active disclosure of inspection results: how to prevent naming & shaming? Since 1 September 2020, the Dutch Food Safety Authority (NVWA) has been given the power to publish certain inspection results (including identification details of the inspected FBO) faster than before. Prior to that date, the legal basis for disclosure could primarily be found in article 8 of the Dutch Freedom of Information Act (in Dutch: Wet openbaarheid van bestuur). This act creates a duty for the administrative body concerned, for example the NVWA, to publicly provide information when this is in the interest of good and democratic governance. However, article 10 of the Freedom of Information Act requires an individual balancing of interests in order to avoid disproportionate disadvantage for the parties involved as a result of the publication. It also prohibits disclosure of certain sensitive information, such as company and manufacturing data that has been confidentially communicated to the government. This blog post explains what has changed since 1 September 2020, which FBOs are affected and what arguments they can use to prevent disclosure.

Since 1 September 2020, the Dutch Food Safety Authority (NVWA) has been given the power to publish certain inspection results (including identification details of the inspected FBO) faster than before. Prior to that date, the legal basis for disclosure could primarily be found in article 8 of the Dutch Freedom of Information Act (in Dutch: Wet openbaarheid van bestuur). This act creates a duty for the administrative body concerned, for example the NVWA, to publicly provide information when this is in the interest of good and democratic governance. However, article 10 of the Freedom of Information Act requires an individual balancing of interests in order to avoid disproportionate disadvantage for the parties involved as a result of the publication. It also prohibits disclosure of certain sensitive information, such as company and manufacturing data that has been confidentially communicated to the government. This blog post explains what has changed since 1 September 2020, which FBOs are affected and what arguments they can use to prevent disclosure.

Additional basis of disclosure as of 1 September 2020

As of 1 September 2020, the NVWA is additionally bound by the Decree on the Disclosure of Supervision and Implementation Data under the Health and Youth Act (in Dutch: Besluit openbaarmaking toezicht- en uitvoeringsgegevens Gezondheidswet en Jeugdwet, hereinafter: Decree on Disclosure), as further elaborated in the Policy Rule on Active Disclosure of Inspection Data by the NVWA (in Dutch: Beleidsregel omtrent actieve openbaarmaking van inspectiegegevens door de NVWA, hereinafter: Policy Rule on Disclosure). This power of disclosure is based on article 44 of the Dutch Health Act (in Dutch: Gezondheidswet). Disclosure in accordance with the Decree on Disclosure does not require the balancing of interests: disclosure of information will simply take place when indicated in the relevant annex to the Decree on Disclosure. Companies that wish to prevent publication of information related to their business will therefore have to invoke factual criteria, such as that the information to be disclosed contains incorrect information or concerns information that is excluded from disclosure in Article 44(5) of the Health Act.

Required actions when companies disagree with disclosure

The publication of information as based on the Decree on Disclosure has consequences for the way affected companies can stand up to prevent disclosure and the speed with which they will need to object. Where the Freedom of Information Act offers affected companies the possibility to share their opinion (in Dutch: zienswijze) in reaction to the administrative body’s intention to disclose the information in question, this possibility does not exist under the Decree on Disclosure. If and when an affected company does not agree with disclosure on the basis of the latter decree, this company has two weeks to object to the respective administrative body’s intention of disclosure and needs to seek interim relief measures within this time frame in order to actually suspend the disclosure. In addition, under the Decree on Disclosure companies are provided the option to write a short response that will be published together with the information subject to disclosure. In this way, affected companies are given the opportunity to provide the outside world with a substantive (but very summary) response to the information to be made public. The Policy Rule on Disclosure in fact also grants this right of response to information disclosed by the NVWA under the Freedom of Information Act.

Relevant for all FBOs?

The aforementioned additional legal basis for disclosure by the NVWA applies for the time being to a limited number of supervisory areas only, namely the inspection results of the NVWA with regard to (i) fish auctions, (ii) the catering industry, and (iii) project-based studies into the safety of goods other than food and beverages. These areas may be expanded in the future, according to the explanatory notes to the Decree on Disclosure.

However, for companies with so-called borderline products that navigate between different regulatory regimes, it is relevant to know that Dutch Health and Youth Care Inspectorate (IGJ) has broader powers to actively disclose inspection results under the Decree on Disclosure. Since 1 February 2019, the IGJ has already been publishing information on the basis of this decree regarding, amongst other, compliance with the Dutch Medicines Act (in Dutch: Geneesmiddelenwet). This means that when the IGJ takes enforcement measures against a FBO handling food supplements or other foodstuffs that qualify as (unregistered) medicines, it may be obliged to make public the respective supervisory information. The same applies to enforcement under the Dutch Medical Devices Act (in Dutch: Wet op de medische hulpmiddelen) – think diet preparations – and the Opium Act (in Dutch: Opiumwet) – think CBD and other cannabis products.

However, for companies with so-called borderline products that navigate between different regulatory regimes, it is relevant to know that Dutch Health and Youth Care Inspectorate (IGJ) has broader powers to actively disclose inspection results under the Decree on Disclosure. Since 1 February 2019, the IGJ has already been publishing information on the basis of this decree regarding, amongst other, compliance with the Dutch Medicines Act (in Dutch: Geneesmiddelenwet). This means that when the IGJ takes enforcement measures against a FBO handling food supplements or other foodstuffs that qualify as (unregistered) medicines, it may be obliged to make public the respective supervisory information. The same applies to enforcement under the Dutch Medical Devices Act (in Dutch: Wet op de medische hulpmiddelen) – think diet preparations – and the Opium Act (in Dutch: Opiumwet) – think CBD and other cannabis products.

An example: melatonin-containing foodstuff labeled as a medicine

An example: melatonin-containing foodstuff labeled as a medicine

An example of a FBO that was faced with disclosure in accordance with the Decree on Disclosure by the IGJ concerns a company involved in melatonin-containing products. The IGJ intended to publish an inspection report on these products, from which it would follow that the products in question qualify as medicines and that the FBO concerned would therefore illegally place them on the market (namely without the required licenses under the Medicines Act). The FBO at stake applied for a preliminary injunction suspending the publication decree. On 8 July 2020, the preliminary relief judge rendered a judgment in this case.

Possible factual criteria to prevent naming & shaming

Although disclosure under the Decree on Disclosure is obligatory and disclosure decisions thus do not require the balancing of interests, the above-mentioned melatonin case gives good insights into the factual criteria that can nevertheless be invoked to prevent disclosure. In this case, the respective FBO brought forward the following arguments.

The respective inspection report excluded from disclosure

Article 3.1(a) of Part II of the Annex to the Decree on Disclosure excludes certain supervisory information from disclosure, including the results of inspections and investigations established as a result of a notification by a third party. The FBO at stake (hereinafter: “Applicant’) takes the position that the present inspection report was initiated as a result of a notification or enforcement request by a competitor. This would mean that the respective inspection report must not be made public.

The preliminary relief judge cannot agree with this position in the present case and rules that the inspection report is clearly related to an earlier letter from the IGJ to the applicant in which it announced the intensification of supervision of melatonin-containing products. Moreover, the case file was silent on a notification or enforcement request by a competitor.

The preliminary relief judge additionally states that it agrees with the IGJ’s viewpoint that the inspection report does not concern a penalty report (the report was drafted within the context of supervision and only indicates that Applicant will be informed about the to be imposed enforcement measure by separate notice). The fact that Applicant had earlier received a written warning for violation of the Medicines Act has no influence on this. The inspection report is therefore neither excluded from publication pursuant to article 3.1(a)(ii) of Part II of the Annex to the Decree on Disclosure, which makes an exception for “results of inspections and investigations that form the basis of decisions to impose an administrative fine”.

Disclosure in violation of the goal of the Health Law: outdated scientific foundation conclusions IGJ

The purpose of disclosure under the Health Act, in the wording of article 44(1) of that act, is to promote compliance with the regulations, to provide the public with insight into the way in which supervision and implementation of the Decree on Disclosure is carried out and into the results of those operations. Pursuant to Article 44a(9) of the Health Act, information should not be made public where this is or may violate aforementioned purpose of disclosure. Applicant takes the position that publication of the present inspection report does not contribute to improved protection of the public or to better information about the effects of melatonin, as a result of which the report should not be disclosed. More specifically, the applicant complains that the report (i) contains obvious errors and inaccuracies, (ii) gives the impression that it concerns a penalty decision, and (iii) is based on an incorrectly used framework to determine whether the qualification of a medicine is met.

The preliminary relief judge first of all notes that the fact that Applicant does not agree with the conclusions of the inspection report does not mean that the report therefore contains obvious inaccuracies. The preliminary relief judge further summarizes Applicant’s position as follows: (i) the IGJ wrongly took a daily dosage of 0.3 mg melatonin to determine the borderline between foodstuff and medicines; (ii) in doing so, the IGJ did not demonstrate that products with a daily dose of 0.3 mg melatonin actually acts as a medicine; (iii) moreover, the product reviews refer to outdated scientific publications (a more recent study by one of the authors thereof as well as more recent EFSA reports have not been included in the inspection report), whereas the current state of scientific knowledge must be taken into account according to established case-law. For these reasons, the preliminary relief judge agreed with Applicant that the IGJ has not made it sufficiently clear that from a daily dose of melatonin of 0.3 mg or more a ‘significant and beneficial effect on various physiological functions of the body’ occurs scientifically – according to the current state of scientific knowledge – and that products with a daily dose of melatonin of 0.3 mg or more act as a medicine”. Having said that, the preliminary relief judge did not accept Applicant’s statement that disclosure is contrary to the purpose of disclosure under the Health Act. Instead, the preliminary relief judge sought to comply with the so-called principles of sounds administration (in Dutch: algemene beginselen van behoorlijk bestuur) and ruled that the disclosure decision was not diligently prepared and insufficiently substantiated.

Incorrect facts

Applicant claims that the inspection report contains various inaccuracies, including the incorrect information that Applicant would produce melatonin itself. Applicant had already raised these inaccuracies in her response to the draft version of the report, but this had not resulted into adjustments in the final, to be published version of the report. The preliminary relief judge ruled on this matter that the IGJ should further investigate Applicant’s concerns and should amend the report where relevant. After all, the content of the report must be correct and diligently compiled. The mere fact that Applicant was given the opportunity to respond to the draft version of the report and that the IGJ responded to this in its decision to disclose the report does not mean that this requirement is met.

Violation of article 8 ECHR: disclosure has a major impact on Applicant’s image

Applicant claims that the planned disclosure will have a major impact on Applicant’s image and that of the natural person involved in the company. This is in violation of article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) concerning the right to respect for private and family life. The Explanatory Memorandum to the Amendment to the Health and the Youth Care Act (in Dutch: Memorie van Toelichting op de Wijziging van de Gezondheidswet en de Wet op de Jeugdzorg) deals with this in detail. It emphasizes that the disclosure of inspection data does normally not constitute an interference with private life, because the data normally relates to legal persons and not to natural persons. The aforementioned Explanatory Memorandum therefore concludes that article 8 ECHR does not preclude disclosure on the grounds of the Health Act. Nevertheless, the court has at all times the competence to review a disclosure decision in the light of that article, in which case it will in fact have to balance the interests involved. In the present case, preliminary relief judge sees however no reason to assume a violation of article 8 ECHR.

Although the above shows that the preliminary relief judge in the respective melatonin case does not agree with all arguments put forward by Applicant, the request for suspension of publication of the contested inspection report was nevertheless granted thanks to factual criteria that were sufficiently substantiated. In particular the (implicit) argument that the conclusions in the inspection report lack a sufficient factual basis affects the essence of the information to be disclosed.

Conclusion

Rapid action is required to prevent active disclosure of inspection results under the Decree on Disclosure as these will usually be published after two weeks. This is not only relevant for FBOs active in the supervisory areas of the NVWA as designated in the Decree on Disclosure, but also for FBOs that operate at the interface of legal regimes under the supervision of the IGJ. To suspend disclosure, interim relief proceedings will have to be instituted as the Decree on Disclosure no longer provides for the possibility of submitting an opinion prior to publication. Moreover, affected companies cannot invoke the argument of suffering a disproportionate disadvantage as a result of the publication. Publication on the basis of the Decree on Disclosure is namely not subject to an individual balancing of interests (apart from an assessment on the basis of article 8 ECHR, insofar relevant). Although the arguments that companies can bring forward to prevent publication are therefore more limited than in the case of disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act, this does not mean that companies cannot successfully object an intention of disclosure. The melatonin case mentioned above is an example of this: conclusions that are not based on most recent science may not be published without adequate justification. Also, facts that are alleged to be incorrect should be further investigated before disclosure.

Trends at Vitafoods … and what you should know if you decide to be part of it

Posted: May 13, 2019 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, beauty claims, cannabidiol, cannabis, Food, Health claims | Comments Off on Trends at Vitafoods … and what you should know if you decide to be part of it From 7 – 9 May 2019, the Vitafoods conference took place again in Geneva. For a few years in a row, I presented at the Education Program. This year I was asked to discuss the application of CBD in food products, which is currently a hot topic. Below, I will share the insight from my presenation, as well as two other trends I came across at the trade show.

From 7 – 9 May 2019, the Vitafoods conference took place again in Geneva. For a few years in a row, I presented at the Education Program. This year I was asked to discuss the application of CBD in food products, which is currently a hot topic. Below, I will share the insight from my presenation, as well as two other trends I came across at the trade show.

(1) Cannabis, cannabis, cannabis

Cannabis was omnipresent at Vitafoods 2019. I do not mean the smell of it, but its application in food, pharma and in cosmetics. FoodHealthLegal being dedicated to food products, this post will uniquely focus on food application of (parts of) Cannabis. In our practice, we also deal with the other applications thereof. As pointed out in an earlier blogpost, FBO’s in the field of Cannabis were recently confronted with a change in the Novel Food catalogue. Since 20 January this year, CBD was declared a Novel Food. In my presentation during Vitafoods, I explained that this does not necessarily mean that each FBO needs to obtain an (individual) NF authorization. In fact, I identified 5 ways to market CBD food products, as further detailed in my slides:

- no Novel Food;

- individual / joint Novel Food application;

- rely on third party authorization;

- take advantage from the transition regime;

- use national consultation procedure.

(2) Nutricosmetics

Food supplements targeting a cosmetic effect, so-called nutricosmetics, were present in great numbers too. The rationale behind these products is that cosmetic effects do not only derive from topical applications but can just as well be achieved via food (“beauty from within”). Communicating the benefits of these products is to some extent easier than communication around “regular” food supplements, as one can rely on so-called beauty claims. These are claims that uniquely target appearance of skin, hair and nails and not any beneficial nutritional or physiological effect on the body. These types of claims are not covered by the Claims Regulation, so one has flexibility in the wording thereof. In practise, these claims are usually supported by efficacy studies, as the burden of proof obviously is on the FBO marketing the nutricosmetic at stake. In addition to beauty claims, a number of health claims relate to beauty as well. The compounds covered include biotin, iodine and Vitamins A, B2 and C amongst others. As a result, attractive general health claims can be used for nutricosmetics, when specific ingredients thereof meet the parameters for these specific claims.

As an example, the product Lycoderm can be mentioned. This is a carotenoids and rosemary blend aimed at enhancing the benefits of topical skin treatment. The product is marketed stating that “antioxidants like carotenoids help balance our skin from environmental stressors such as UV rays”. The shorter version thereof could be “carotenoids help maintain healthy, smooth skin.” So far, no authorised health claim for carotenoids is in place, but it is possible to make a beauty claim regarding the effects thereof in a nutricosmetic (if powered by science). When using the authorised health claim for Vitamin E (“contributes to the protection of cells from oxidative stress”), a short attractive claim could read “beauty comes from within.”

(3) Digital nutraceuticals

This is a new phenomenon according to which nutraceuticals are powered by digital support. Various examples of apps developed by manufacturers of nutraceuticals operating in a B2B context were shown, aiming to enhance the appreciation of the consumer in a B2C context. More than once, such digital support could be customized for each individual client, so that a whole new digital business is developing around food supplements.

As an example, the product Metabolaid can be mentioned. This is a food supplement manufactured by Monteloeder aiming at weight control by controlling the appetite of consumers. Clinical studies are reported to have shown that the intake of this product, together with a healthy diet and regular exercise, helps consumers to manage their body weight, blood pressure, cholesterol and glucose levels. Monteloeder has also designed an app, enabling the consumer to monitor his/her daily habits, including eating hours, frequency and sleep. Furthermore, this app allows the connection with other wearables to detect health related parameters like heart rate, steps taken and body weight. This should enable the consumer to achieve positive changes in lifestyle habits, by offering a more thorough control over his/her overall health.

Obviously, such digital support of a nutraceutical requires a decent data protection strategy. Not only this is required to be GDPR compliant, it is also of the essence to gain and maintain consumers trust. Any company offering such solution should clearly explain in its privacy policy for what purpose consumer data are used, what are the legal grounds for processing and with whom personal data will potentially be shared. In the case of Monteloeder, offering customized apps for clients, it will be interesting to know who will be the controller regarding consumer data: Monteloeder or its client? If the client is setting the means & purposes for processing, is Monteloeder than completely out of scope, or is it actually operating as a controller as well? It is of the essence that the consumer is properly informed thereof, especially now that the data generated most likely qualify as “data concerning health”. The GDPR applies a very strict regime for processing these data and Member States are at liberty to formulate national restrictions as well.

Take home

Overall the Vitafoods conference offered many new insights. When adopting these, check before going to market whether your regulatory strategy is up to standards!

Cannabis derived food products – what’s the current state of play?

Posted: February 25, 2019 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, cannabidiol, cannabis, Enforcement, Food, Health claims, novel food | Comments Off on Cannabis derived food products – what’s the current state of play? Recently, CBD food products were qualified as Novel Foods requiring a market authorization. The lively trade in these products therefore currently seems to be at risk. However, not all cannabis derived products are Novel Foods. What is the current state of play regarding these products and how is enforcement going to look like?

Recently, CBD food products were qualified as Novel Foods requiring a market authorization. The lively trade in these products therefore currently seems to be at risk. However, not all cannabis derived products are Novel Foods. What is the current state of play regarding these products and how is enforcement going to look like?

Current state of play re. cannabis derived products

In the European Union, the cultivation of Cannabis sativa L. varieties is permitted provided they are registered in the EU’s ‘Common Catalogue of Varieties of Agricultural Plant Species’ and the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content does not exceed 0.2 % weight per weight. The Common Catalogue is embodied in the EC Plant Variety database, which currently lists 68 species of Cannabis sativa. Some products derived from the Cannabis sativa plant or plant parts such as seeds, seed oil, hemp seed flour and defatted hemp seed have a history of consumption in the EU and therefore, in principle, are not novel.

What’s new?

This is different for extracts derived from Cannabis sativa L. and derived products containing cannabinoids, such as cannabidiol (CBD). It follows from a recent clarification of the Novel Food Catalogue that these products are considered Novel Foods, as a history of consumption regarding these products has not been demonstrated. This applies to both the extracts themselves and any products to which they are added as an ingredient. If for instance CBD is added to hemp seed oil, the product can no longer be marketed just like that and requires market authorization. The status of Novel Food also applies to extracts of other plants containing cannabinoids and to synthetically obtained cannabinoids.

How does the market of CBD food products currently look like?

Currently, the market in CBD food products is flourishing. A variety of CBD nutraceutical products is being offered for sale, such as HempFlax CBD, CBD oil, but also CBD-infused tea, honey or sweets. Although there is no hard-scientific evidence, many health benefits are connected to CBD food products, such as stress reduction, good night rest and providing energy and increasing resistance. Contrary to products containing THC (tetrahydrocannabinol), which is also extracted from cannabis, you do not get high on CBD food products, as this is not a psychoactive substance.

Medicinal use of cannabis

The use of cannabis derived CBD in food is not to be confused with medicinal use of cannabis. In most cases of medicinally applied cannabis, the active ingredient is THC, not just CBD, or a combination of THC and CBD. Although medicinally applied cannabis does not play a role in the cure of diseases, scientific publications show it can alleviate suffering from diseases, for instance nausea, decreased appetite, slimming or weakening due to cancer.

Consequences for business of the change in legal framework

Due to the qualification of CBD food products as Novel Foods, the lively trade in these products is currently at risk. Any Novel Food has to obtain a market authorization in order to get market access. CBD food products currently marketed may face enforcement measures, unless they can benefit from the transition regime laid down in the Novel Foods Regulation. According to this transition regime, any product that did not fall within the scope of the former Novel Foods Regulation, was lawfully marketed prior to 1 January 2018 and for which an application for market authorization is filed before 2 January 2020, can continue to be marketed until an authorization decision has been taken. While this transition period is in principle drafted for Novel Foods that fall into one of the new novel food categories under the new Novel Foods Regulation, it is in the spirit of the transition regime to also include the CBD scenario.

Pending CBD-application and expected EFSA opinion

Currently, one application for the authorization of a CBD food supplement is pending. The application was made by the company Cannabis Pharma from the Czech Republic and is based on publicly available safety and toxicological information and toxicity reviews. More in particular, the scientific data has been gathered from acute and long-term toxicity studies in animals and tolerance studies in humans. The data package submitted aims to support the safety of the use of CBD in food supplements for adults with a daily intake of up to 130 mg or 1.86 mg/kg body weight. It is reported by various sources that an EFSA opinion is awaited this March (see here and here).

Any benefits for the CBD market of a positive EFSA opinion?

Contrary to the situation under the former Novel Foods Regulation, the authorizations granted under the current Regulation have a generic nature. This means that any other company meeting the conditions of use stated in the authorization, would be at liberty to market CBD food supplements as well. The pending application made by Cannabis Pharma is therefore followed with great interest by the CBD market. As they do not seem to rely on data protection, a granted authorization would pave the way for other food supplement companies. It is not certain if this will happen still this year. If and when EFSA grants a positive opinion this March, the European Commission still has 7 months to submit an implementing act to the PAFF Committee. Upon a positive opinion of the PAFF committee, such implementing act could be quickly adopted. If the PAFF Committee has no opinion or a negative opinion, 1 or 2 months should be added to the procedure as a minimum.

Ireland: some CBD food products can be marketed

Meanwhile, there is some guidance available at Member State level. The Irish Food Safety Authority notes that recently a large number of CBD food products entered the market, typically marketed as food supplements in liquid or capsule form. Depending on the manufacturing process applied, the trade in CBD oil is not prohibited, as this oil naturally contains low levels of CBD, which is considered a non-psychoactive compound. This applies to CDB oil obtained by cold-pressing the hemp seeds. If and when the oil is obtained by supercritical CO2 extraction, then a Novel Food authorization is mandatory.

Denmark: available guidance not crystal clear

According to the Danish Ministry of Environment and Food, a number of Cannabis-derived products are not considered Novel Food, notably hemp seeds, seed flour, protein powder from seeds and seed oil from the Cannabis sativa L. varieties listed in the EC Plant Variety Database that are free from or contain low levels of THC. If these products contain CBD, the regulatory status is not exactly clear. According to the guidance of the Danish Food Ministry, the current status is that pure cannabidiol as well as hemp products with high (concentrated) levels of CBD or other cannabinoids are covered by the Novel Foods Regulation. It is not explained what is understood by “high levels of CBD”, but on the other hand an absolute prohibition to market these products in Denmark does not seem to apply.

Absolute prohibitions: Belgium and Austria

Other Member States seem to be stricter than Ireland or Denmark. For instance, the Austrian Health Ministry has made it perfectly clear that food products containing any type of cannabinoid extract without a Novel Food authorization are prohibited to be put on the market. In Belgium, the Federal Agency on Safety in the Food Chain has clarified that the production and marketing of food products based on cannabis is prohibited. The rationale is that the plant Cannabis sativa is mentioned in an annex to a national Decree listing dangerous plants that cannot be used for food production. The prohibition primarily seems to target the potentially dangerous substance of THC and allows derogations on a case-by-case basis, but not regarding food products containing CBD. These are considered Novel Foods requiring a market authorization.

Enforcement directed against (medical) claims in the Netherlands

Until CBD was declared a Novel Food, the trade in CBD food products was not prohibited in the Netherlands. Contrary to the substance TCH, the substance CBD is not mentioned in the Dutch Opium Act, listing prohibited substances having a psycho active effect. This does not mean that the trade in CBD food products was allowed just like that. In practice, enforcement in the Netherlands has been directed against the use of any unauthorized medical claims. A medical claim is any information according to which a food product could have a therapeutic or prophylactic effect. When using such a claim, one comes into the realm of the Medicinal Product Act, according to which it is prohibited to market and advertise any medicinal product without a market authorization. The Dutch Food Safety Authority announced fines up to

€ 10.000 regarding the sale of CBD food products in several cases (see here and here). Any food business operator that is serious about his business in CBD food products will therefore not only check the applicability of the Novel Foods Regulation to his products, but also carefully draft his advertisement for this type of product.

Conclusion

The production and marketing of food products derived from Cannabis sativa L. in the EU has been considerably restricted since CDB food products were recently declared to be Novel Foods. However, not all cannabis-derived food products require market authorization. Pending the evaluation of the Novel Food application filed for a CBD food supplement by the Czech company Cannabis Pharma, it is worthwhile for other CBD food products to verify whether they can benefit from the so-called transition regime embodied in the Novel Foods Regulation. Due to differences between legislation in the Member States, this may differ from country to country. Also, it is important to carefully position your CBD food product, in order to avoid any medical claims.

The author ackowledges Jasmin Buijs, paralegal at Axon, and Max Luijkx, intern at Axon, for their valuable input.