New Genomic Techniques: threat or opportunity?

Posted: October 23, 2023 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Food, New Genomic Techniques, organic |Comments Off on New Genomic Techniques: threat or opportunity? Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) do not generally receive a warm welcome from the average EU citizen. Possibly this is a case of ‘unknown makes unloved’. But GMOs can also bring positive things, for example, in the field of plant breeding. This summer, the European Commission published a proposal for an NGT Regulation. What exactly does this proposal entail and what are the expected consequences in practice? And how was this proposal received by the European Parliament in its draft report of 16 October last in the first reading of the legislative procedure?

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) do not generally receive a warm welcome from the average EU citizen. Possibly this is a case of ‘unknown makes unloved’. But GMOs can also bring positive things, for example, in the field of plant breeding. This summer, the European Commission published a proposal for an NGT Regulation. What exactly does this proposal entail and what are the expected consequences in practice? And how was this proposal received by the European Parliament in its draft report of 16 October last in the first reading of the legislative procedure?

Potential benefits GMOs and reluctance

GMOs can help develop plants that are more drought tolerant or less susceptible to certain fungi. This reduces the need for pesticides in cultivation, precisely one of the objectives of the EU Farm-to-Fork strategy that the Commission published at the beginning of its mandate in May 2020. At the same time, in the Netherlands the proposal for the NGT Regulation prompted Odin, Demeter, Ekoplaza and Greenpeace, among others, to start a petition calling for “Keep our food genetically modified free.” (in Dutch: Houd ons voedsel gentech vrij). At the time of writing this blogpost, the petition counts 47.709 signatories.

Scope of application NGT Regulation

The intended Regulation applies to NGT plants and to NGT products, meaning food and feed containing or consisting of or produced from NGT plants and other products containing or consisting of such plants. NGT plants are obtained from the following two genomic techniques or a combination thereof:

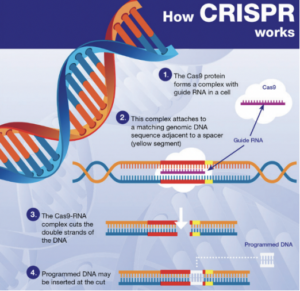

- Targeted mutagenesis: this is a technique that results in changes to the DNA sequence at precise locations in an organism’s genome;

- Cisgenesis: this is a technique that results in the insertion, into the genome of an organism, of genetic material already present in the total genetic information of that organism or another taxonomic species with which it can be crossed.

In essence, NGTs are genomic techniques such as CRISPR-Cas9. These techniques result in more targeted genomic modifications than older genomic techniques, which often involve the introduction of heterologous genetic material. The European Commission therefore recognizes that any risks associated with the use of NGTs are lower than those associated with older genetic techniques. This is what the risk assessment in the draft Regulation specifically addresses.

Two specific regulatory regimes for category 1 and category 2 NGT plants

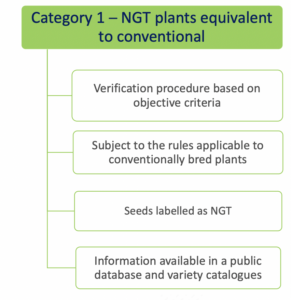

- Category 1 NGT plants: these plants are considered equivalent to conventionally bred plants based on the criteria in Annex I

of the NGT Regulation and as such do not need to undergo complete GMO risk assessment. Instead, a notification to a national GMO authority or to EFSA is sufficient;

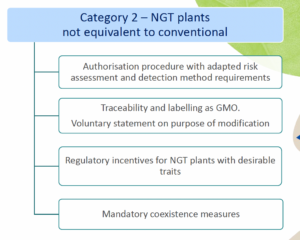

of the NGT Regulation and as such do not need to undergo complete GMO risk assessment. Instead, a notification to a national GMO authority or to EFSA is sufficient; - Category 2 NGT plants: these plants are considered as GMOs and as such are subject to the GMO rules for authorization, traceability and labeling, however according to a modified system of more targeted risk analysis.

In addition to NGT plants, these regulations also apply to NGT products: that includes foods with ingredients made from such plants. This is why this proposed Regulation is so relevant for innovative food business operators.

In addition to NGT plants, these regulations also apply to NGT products: that includes foods with ingredients made from such plants. This is why this proposed Regulation is so relevant for innovative food business operators.

As mentioned above, for category 1 NGT plants, a notification procedure takes place and for category 2 NGT plants a full swing risk assessment. Both procedures involve a substantive assessment of whether plant material produced using targeted genetic techniques complies with the specifically developed rules for risk assessment. It is expected that the procedure for category 1 NGT products can be completed within a year, while the permit process for category 2 NGT foods is actually identical to that for regular GMOs. An innovation is that the NGT Regulation provides certain incentives for specific category 2 NGT foods that should speed up or simplify the assessment process.

Transparency regarding genetic engineering

Producers of organic products and advocacy organizations are concerned that, based on the NGT Regulation, genetically engineered food is walking into stores undetected. But is this concern justified? Based on the current text of this Regulation, both category 2 and even category 1 NGT products are excluded from organic production. Indeed, in the consultation process leading up to the NGT Regulation, the freedom of choice of consumers to buy food containing or not containing GMOs appeared to be an important issue. At the same time, the European Parliament considers the prohibition for organic farmers to use conventional-like category 1 NGT’s neither science-based, nor politically justifiable. It therefore calls in its draft report to create a fair level playing field and to only ban category 2 NGT plant material from organic production.

Category 1 NGT products listed in public database?

Whether or not allowed in organic production, there is no specific labeling requirement for Category 1 NGT products (Q 11 from EC Q&A). However, plant material with Category 1 NGT status must be included in a public database, expected to be similar to the Novel Food consultation database. In the Commisson’s proposal, plant reproduction material with Category 1 NGT status must additionally be labeled as such, with the identification number of the plant from which it is derived. At the level of production, this would provide an extra safeguard for distinguishing between conventionally grown crops and crops in which genetic engineering has been used. The European Parliament is however critical about this additional requirement in its draft report. It considers such discriminatory since category 1 NGT plants are conventional-like. According to the European Parliament, transparency and consumer choice are sufficiently ensured by disclosure in a public database. Therefore, even if the modifications proposed by the European Parliament will stand, there is no reason to believe that foods produced using CRISPR-Cas9 could go completely unnoticed.

Conclusion

With current changes in climate and constraints on available agricultural land with a growing world population, plant harvests will come under increasing pressure. NGTs are expected to meet the need to better equip plants for such challenges. The proposed NGT Regulation aims to simplify and thereby accelerate market access for such technology. For category 1 NGT products, except for a few open ends, this premise seems feasible in practice. A huge improvement with respect to current legislation is that the nature of the genetic change is decisive for risk evaluation, not the technique by which it is produced (product-based vs. process-based approach). For category 2 NGT products, market access is not expected to become much simpler based on the current proposal. Nevertheless, this proposal looks hopeful for plant innovations and thus for our food products of tomorrow. Also, there seems to be sufficient transparency to distinguish between crops produced with and without genetic engineering. My very bald hope would be that based on positive experiences with this regulation, the scope of this regulation will be extended to other fields, such as cellular agriculture and/or fermentation-based products. We will continue to follow closely how this legislation will develop.

Source images

- How CRISPR works: EU Parliament briefing on Plants produced by new genomic techniques

- Category 1 NGT plants: PPT DG Santé on Farm to Fork Strategy presented during EFFL Conference on 19 October 2023.

- Category 2 NGT plants: idem (2)

Thanks to my colleagues Jasmin Buijs and Max Baltussen for their valuable feed-back.