A drink made from monk fruit – novel food or not?

Posted: August 27, 2024 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Food, novel food |Comments Off on A drink made from monk fruit – novel food or not?UK High Court quashes FSA decision on novelty of monk fruit decoctions

Introduction

In the EU, food business operators (FBOs) have the responsibility to ensure that the food they are marketing is not unsafe. Most of the food products do not require prior market authorization, novel foods being one of the exceptions to the rule. For novel foods market authorization is granted based on an extensive safety evaluation by EFSA. If an FBO is unsure if its product / ingredient falls within the scope of the EU Novel Food Regulation, it can submit a voluntary consultation to a Member State, where the FBO intends to first market its product. The Member State competent authority will review the data submitted to establish if a history of use before 1997 can be established. In the affirmative, the product will not be considered novel. Examples of products not considered novel include pea protein concentrate and the Chinese pepper Capsicum chinense.

This blogpost covers the 19 March 2024 decision of the UK High Court on the novelty of a monk fruit decoction evaluated during a national consultation. This procedure was initiated by Guilin GFS Monk Fruit Corporation (Guilin GFS) against a joint decision of the UK Food Standards Agency (FSA) and the Food Standards Scotland (FSS). Guilin GFS is a world leader producer and manufacturer of monk fruit decoctions, having a 50 % global market share. Monk fruit is a small sub-tropical melon originating from China. Monk fruit decoctions can be applied to a wide range of foods and drinks as a sweetener and is popular for its low-calorie profile.

This blogpost covers the 19 March 2024 decision of the UK High Court on the novelty of a monk fruit decoction evaluated during a national consultation. This procedure was initiated by Guilin GFS Monk Fruit Corporation (Guilin GFS) against a joint decision of the UK Food Standards Agency (FSA) and the Food Standards Scotland (FSS). Guilin GFS is a world leader producer and manufacturer of monk fruit decoctions, having a 50 % global market share. Monk fruit is a small sub-tropical melon originating from China. Monk fruit decoctions can be applied to a wide range of foods and drinks as a sweetener and is popular for its low-calorie profile.

Figure 1 monk fruit image taken from the movie shown at www.monkfruitcorp.com

Applicable test and EC Guidance

After Brexit, the United Kingdom has maintained the EU Novel Food Regulation. Therefore, this decision is also of relevance for EU Member States. Under this applicable framework, the relevant test is whether monk fruit decoctions were used for human consumption to a significant degree in the EU or in the UK prior to 1997 (so-called history of consumption or HoC test). To adduce proof of a HoC, guidance can be taken from the Commission Guidance on Consumption to a Significant Degree dating back to 1997 (EC Guidance). In this context, it is important to note that the EC Guidance itself recognizes the difficulties of proof of significant use by the passage of time. It explicitly states that the examples of use are by no means exhaustive.

Evidence adduced

To meet the test on a HoC, Guilin GFS had adduced substantive evidence, including the following.

- Certificates of origin re. the export of processed foods monk fruits from mainland China to the UK during the period of 1998 – 2000;

- Evidence from a qualitative study from 2018 comprising face to face interviews with 71 participants in the UK and the EU demonstrating that processed foods containing monk fruits were sold in the EU / UK prior to 1997;

- Evidence from over 1.000 questionnaires as part of a quantitative population sample study from 2020 in the UK amongst people from Chinese descent re. their purchases of processed monk fruit;

- A survey in UK / EU supermarkets re. the types of monk fruit products sold before 1998;

- Signed declarations from restaurant owners, FBOs and the London Chinatown Chinese Association attesting the sale and / or consumption of monk fruit decoctions in the UK / EU prior to 1997.

FSA and FFS decision and rationale

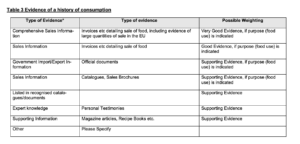

On 8 September 2022, FSA and FFS rendered the decision that Guilin GFS did not meet the HoC test (the Decision). FSA and FFS considered the evidence too small in samples and none of this evidence hit the box of “Very Good Evidence”. This is the type of evidence referred to in Table 3 to the EC Guidance reproduced below. The table at stake contains examples of evidence that might be adduced to meet the HoC test, such as invoices detailing the sale of the food product at stake, including evidence of large quantities of the sale in the EU (“Very Good Evidence”), mere invoices detailing the sale of the food at stake (“Good Evidence”) and magazine articles (“Supporting Evidence”). The main reason why FSA and FFS considered the evidence not up to standards was because invoices demonstrating sales of monk fruit decoctions prior to1997 were missing. Also, the FSA considered that personal testimonies were inherently incapable of demonstrating a significant HoC without verification of an independent source.

Figure 2: Table 3 to the EC Guidance on Consumption to a Significant Degree

Revision procedure and disclosure of FSA decision making process

Guilin GFS did not agree and initiated a revision procedure before the UK High Court on 2 December 2022, for which the hearing took place on 29 February 2024. The beauty of this procedure is that it provides full disclosure on all relevant documentation leading up to the Decision, including internal FSA correspondence conducted by its Novel Food policy advisors, as well as input from the FSA Social Sciences Team. This is an independent expert team, providing strategic advice to FSA. Contrary to the Novel Food FSA policy advisors, the Social Sciences Team considered the qualitative and the quantitative studies of Guilin to be reliable and robust. The Social Sciences Team did have a few verification requests to FSA’s Novel Food policy officers. However, according to Judge Calver, FSA’s Novel Food policy officers placed these questions out of statistic context to which they relate to validate the conclusion they reached earlier. Also, FSA’s Novel Food policy officers did not ask clarification questions to Guilin GFS when they reached their conclusion that monk fruit concoctions should be considered novel within the UK. Strikingly enough, they even reached this conclusion before the official validation of the dossier.

Debate during revision procedure

Guilin GFS opposed the Decision based on three legal grounds.

(1) It is incorrect that evidentiary requirements of the test for novelty under the Novel Food Regulation could not be met in the absence of pre-1997 sales invoices and data.

(2) It is incorrect that personal testimonies were categorically incapable to demonstrate a significant HoC unless verified by independent source.

(3) It is incorrect that it was necessary to demonstrate that monk fruit was consumed “exclusively for food uses”.

In reply, the Agencies served four witness statements from Novel Food policy advisors to “elucidate the reasons for the Decision.” Justice Calver states that based on the fact that these statements were made 15 months after the Decision, these need to be carefully scrutinized as there is a temptation to bolster and rationalize the Decision under challenge. Evidence that goes beyond elucidation and clarification is not permitted. When evaluating the witness statements, Justice Calver concludes the following.

Ad (1) The Agencies applied Table 3 to the EC Guidance too rigidly. Instead of considering “the whole picture” of evidence submitted by Guilin GFS, the Agencies saw that according to Table 3 the study results submitted by Guilin GFS did not qualify as “Very Good Evidence” or “Good Evidence”. They have then classified them as amounting “only” to “supporting evidence” “as defined in the Guidance”. This sentence makes clear that the Agencies consider anything other than invoices pre-1997 to be an inferior type of evidence as a category, amounting only to supporting evidence, which is not sufficient in itself to demonstrate a significant HoC.

Ad (2) The Agencies erroneously take the view that the evidence submitted by Guilin GFS’s should have been independently verified. There is no such requirement in the law or in the EC Guidance. Furthermore, the studies handed in by Guilin GFS had been qualified as reliable and robust by the Social Sciences Team. Also, with respect to personal testimonies, it is hard to conceive how these should be verified by third parties. As rightfully pointed out by Guilin GFS, such a requirement would frequently render personal testimonies redundant.

As a result, Judge Calver accepts grounds (1) and (2) and he considers the Decision flawed at these points. Moreover, he does not accept the four witness statements, as they try to re-write the reasoning in the Decision, which cannot stand with the wording of that document itself.

Ad (3) Finally, Judge Calver rules that the Agencies misapplied the relevant test when stating in the Decision that it was necessary to demonstrate that monk fruit was consumed “exclusively for food uses. The fact that the evidence submitted by Guilin GFS demonstrated a mixed use of monk fruit, in addition to food uses also including plant based medicinal products and even toothpaste, does not preclude establishing food use prior to 1997 in the EU or in the UK.

As a result, the claim for judicial review succeeds, the Decision is quashed, and the Agencies are ordered to re-consider the Claimant’s application in the light of this judgement. We can now see in the press that the Irish Food Safety Authority is reconsidering the novel food status of monk fruit extract and also the UK’s Food Standards Agency (FSA) has changed its stance regarding these products. The FSA now concludes that monk fruit concoctions are not a novel food, meaning that they can be used in food and beverages marketed in the UK. Reliable sources informed me that in the next weeks the Irish authorities – on behalf of the EU – are expected to issue a similar opinion to the UK.

Does this UK decision also apply for the EU?

In my opinion, this question should be answered positively. Rationale: according to the EC Guidance, an “established history of food use to a significant degree in at least one EU Member State is sufficient to exclude the food from the scope of Regulation (EU) 258/97.” The United Kingdom was an EU Member State during the period to which the evidence collected by Guilin GFS relates. The fact that Brexit occurred in 2020 does not change this. This also follows from the following statement in the EC Guidance: “The deadline 15 May 1997 is applicable to all Member States, irrespective from the date of accession to the EU.” By analogy, the same should apply in case of withdrawal of a Member State from the EU.

What can we learn from this decision?

In the first place, that it is a tough job to collect relevant evidence to establish a history of food use prior to 15 May 1997 in the EU (or the UK), especially since we are more and more moving away from this date. But it is doable. When looking at Guilin GFS, we can see that collecting product information, in combination with qualitative and quantitative data and affidavits can actually help to succeed in establishing such history of food use. Provided of course, you have a skilled lawyer at work to present your case. In the case at hand, the lawyers at work did an excellent job. One of these skilled lawyers is Brian Kelly, with whom I have been working together for more than 10 years now. Kudos to Brian!