A guide to the Dutch sustainable certification jungle in food

Posted: February 13, 2017 Filed under: Food, Information | Tags: certification, logo, private standards Comments Off on A guide to the Dutch sustainable certification jungle in food In the beginning of the new calendar year, people tend to stick to new year’s resolutions, such as eating healthier. In supermarkets and other stores choosing healthy/ sustainable products is made easy by means of certification. Certification, mostly in the form of a logo or picture, is a way of branding your product to stand out from your competitors. However, certification options are so broad that consumers have to spend a great deal of time to familiarize themselves with all the available certifications to make an informed choice. To enable the consumer to make an informed choice, the Dutch organization Milieu Centraal (a Dutch public information body on environment and sustainability) published a certification overview on their site, including an app (further keurmerkenwijzer). The keurmerkenwijzer provides an overview of all available certifications (not limited to food) and a ranking of the different organizations responsible for the certification. This blogpost will elaborate on certification in general and recent developments on the national Dutch certification regarding food, including the healthy choice (ik kies bewust) logo. This blog also includes elaboration on two separate apps, the abovementioned keurmerkenwijzer and the EtiketWijzer, which was presented at the Dutch food top 2017 as the replacement for the national certification.

In the beginning of the new calendar year, people tend to stick to new year’s resolutions, such as eating healthier. In supermarkets and other stores choosing healthy/ sustainable products is made easy by means of certification. Certification, mostly in the form of a logo or picture, is a way of branding your product to stand out from your competitors. However, certification options are so broad that consumers have to spend a great deal of time to familiarize themselves with all the available certifications to make an informed choice. To enable the consumer to make an informed choice, the Dutch organization Milieu Centraal (a Dutch public information body on environment and sustainability) published a certification overview on their site, including an app (further keurmerkenwijzer). The keurmerkenwijzer provides an overview of all available certifications (not limited to food) and a ranking of the different organizations responsible for the certification. This blogpost will elaborate on certification in general and recent developments on the national Dutch certification regarding food, including the healthy choice (ik kies bewust) logo. This blog also includes elaboration on two separate apps, the abovementioned keurmerkenwijzer and the EtiketWijzer, which was presented at the Dutch food top 2017 as the replacement for the national certification.

Logo / certification

What is certification? The owner of a certification scheme has a set of rules commonly referred to as private standards, which the owner or a third party enforces. Private standards are voluntary rules, as opposed to national legal norms, which are binding. Food business operators (further: FBOs) can comply with these standards and in return (if they comply) are enabled to use the logo corresponding to those standards. The certification owner owns the logo as well as the standard; usually, the producer pays a fee to the certification owner to use the logo corresponding to the standard. If a FBO complies with a private standard it does not automatically mean the FBO complies with all legal requirements set in national or international law. However, private standards have the tendency to be stricter than national/ international law, and can even encompass rules, which are not part of the national and international law applicable on FBOs.

Scope and enforcement of private standards

Private standards are not limited by geographical area or jurisdiction. This is the reason private standards are used in third countries to ‘up’ the legal standards for the producers in third countries. Private standards contain enforcement measures, often in the form of high fines or exclusion from the private standard. In this way a separate enforcement mechanism is created to enable the certification owner to enforce in case of non-compliance without the interference of the national public enforcement in that particular country. In other words, private standards are a mean to privately enforce (stricter) standards in the food sector.

Rationale certification

Certification schemes are private or semi-private initiatives to enable consumers to see in one view, which products comply with the corresponding standards. Standards can be focused on sustainability, working conditions, animal welfare, or other elements of the production of the product. Even for package material certification schemes are available. FBO’s who bring foodstuffs to the market want to communicate through the use of certification. The incentive for FBOs to use certification on their foodstuff is to persuade consumers to purchase their product.

Large proliferation

A potential problem for FBOs using certification is the proliferation of certification schemes; the number of certification schemes has increased over the years and at this point, over 200 certification schemes exist which focus on sustainability. Research published in 2015 by Milieu Centraal and in 2016 by The Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM) both linked the diminished trust in certification schemes to the large number of available schemes.

Keurmerkenwijzer

To enable consumers to quickly find the information on certification schemes in general and more information on all individual certifications, including a rating of the schemes, the keurmerkenwijzer was launched by Milieu Centraal. The keurmerkenwijzer provides an overview of all available certification schemes (which focus on sustainability) and provides information to the consumers on the following aspects; environment, animal welfare, social, control and transparency. Because of the wide variety of certification schemes, the State Secretary for Economic Affairs was tasked to find a way to guide consumers in the ‘jungle of certification schemes’, to work towards a more sustainable food consumption. The keurmerkenwijzer is the presented solution to the proliferation of certification schemes.

Heathy choice logo

The Dutch national certification scheme for foodstuffs is the healthy choice logo (het vinkje), which used to be owned by the foundation ‘I make a conscious choice’ (stichting ik kies bewust). There are two separate logos, a green and a blue checkmark. The green is the healthy choice, meaning the product is part of the recommended dietary guidelines as provided by the Health Council of the Netherlands (Gezondheidsraad). The blue logo is the conscious choice, meaning that the product is not taken up in the dietary guidelines, but compared to reference products are healthier than the benchmark product; for instance, the product contains low amounts of salt and saturated fats compared to benchmark foodstuffs. The national legal basis can be found in article 11 of the Commodities Act Decree on food information. In short, the certification has to be well recognized by consumers (they know what it stands for) and the standards should be based on science.

Criticism Healthy Choice logo

A compliant and recognized national (or even Europe-wide) certification could be the solution for consumers to make an informed choice. However, the national certification met resistance from consumer organizations. The resistance against the certification led to the filing of a formal complaint (the link provides the full complaint) by the consumer organization (Consumentenbond). The conscious choice logo was considered non-compliant and misleading. In short, both logos were not as well-known to consumers and the scientific substantiation of the certification is lacking, and thus were not in compliance with the abovementioned national law. The foundation symbolically transferred both logos and the best in class criterion (developed by the foundation) to the minister as a result. The foundation will remain in business until all products containing the logo are no longer on the shelves. However, the foundation will be downsized in the course of 2017. The secretary and the website will remain in business as long as the logo’s are still used on products.

App EtiketWijzer

Instead of a new or ‘improved’ national certification scheme, the decision was taken to develop an app for consumers replacing the certification scheme with an app to make healthier choices in food. Currently, the app (EtiketWijzer) is being developed (test phase) by the Netherlands Nutrition Centre (voedingscentrum). The EtiketWijzer focuses on the information on the foodstuff as such, instead of the certification schemes. Albert Heijn, Jumbo and Superunie, are involved in testing the app. The app currently, only works on certain private brands and premium brand products. By the end of 2017 a version for consumers should be available. The aim of the app is to encompass all foodstuffs (of the retailers participating), available in the final version.

Conclusion

The available certification schemes and corresponding logos are many, because of this ‘jungle’ of available certification schemes consumers lose trust in the available schemes. The app developed by Milieu Centraal enables consumers to get informed easily on all available certification schemes and to rate them. Assuming the number of certification schemes will not diminish drastically, the keurmerkenwijzer could be a helpful tool for consumers to make an informed choice. An option to clear the jungle would be to use a Europe-wide certification scheme. However, developing an app to inform the consumers is in our opinion fighting the symptoms, not the root of the problem; the proliferation of the certification schemes.

The EtiketWijzer potentially covers all foodstuffs, regardless of certification. However, the app is under development and should encompass all available foodstuffs to provide full information on healthy foodstuffs. Perhaps the keurmerkenwijzer could be integrated into the EtiketWijzer to ensure consumers are enabled to quickly access all information on both healthiness and sustainability of the foodstuffs without a proliferation of apps.

The author thanks Floris Kets for his contribution to this post.

Nothing left to hide? Status quo on Dutch bill permitting active disclosure of food safety inspection results

Posted: November 9, 2016 Filed under: Disclosure of information, Enforcement, Food | Tags: disclosure, enforcement, inspection, NVWA Comments Off on Nothing left to hide? Status quo on Dutch bill permitting active disclosure of food safety inspection results Recently, an amendment to the Dutch Health Act (Gezondheidswet) was voted in Dutch Parliament, allowing the Dutch Food Safety Authority (Nederlandse Voedsel en Warenautoriteit or NVWA) to actively disclose its inspection results. The change in the Health Act equally applies to inspection results obtained by the Dutch Health Inspectorate (Inspectie Gezondheidszorg or IGZ) and therefore, it received broad interest from the pharmaceutical, medical devices, and the food industry and their legal practitioners. Three meetings on this topics were organised by respectively the Dutch association of Food Law (NVLR), the Dutch Pharmaceutical Law Association (VFenR) and by the Dutch organisation for food retail and management VMT. This post will put you up to speed on the actual changes to be applied to the Health Act, as well as on the expected consequences of their implementation for food business operators (FBOs).

Recently, an amendment to the Dutch Health Act (Gezondheidswet) was voted in Dutch Parliament, allowing the Dutch Food Safety Authority (Nederlandse Voedsel en Warenautoriteit or NVWA) to actively disclose its inspection results. The change in the Health Act equally applies to inspection results obtained by the Dutch Health Inspectorate (Inspectie Gezondheidszorg or IGZ) and therefore, it received broad interest from the pharmaceutical, medical devices, and the food industry and their legal practitioners. Three meetings on this topics were organised by respectively the Dutch association of Food Law (NVLR), the Dutch Pharmaceutical Law Association (VFenR) and by the Dutch organisation for food retail and management VMT. This post will put you up to speed on the actual changes to be applied to the Health Act, as well as on the expected consequences of their implementation for food business operators (FBOs).

Importance of inspection results

Inspection results are important for whom it concerns directly (inspected companies, as they provide answers to questions such as: is your organisation compliant? Will a fine be imposed? Inspection results are furthermore of interest to others, such as consumers, journalists and other companies, including competitors, for a number of reasons. These reasons include (but are not limited to) knowing where to supply from and what places to avoid, the possibility to check if your supplier’s manufacturing processes are up to standards and the option to stay informed on what challenges your competitor is meeting.

Active vs. passive disclosure

All administrative bodies disclose information, on their website, in social media, in leaflets, etc. Under the Dutch Act on Public Access to Government Information (Wet openbaarheid van bestuur or WOB) citizens have the right to file a request for information on administrative matters. The disclosure of such information on request of a person is called passive disclosure. Such disclosure does not take place publicly, but the information concerned will solely be provided to the person who filed the request, unless it is rejected based on the limited grounds specified in the WOB. Active disclosure on the other hand means that the information is disclosed by an administrative body prior to any request for information. Such information is publicly available after disclosure. In case of inspection results of the NVWA, these will most likely be published on the website this administrative body.

Rationale disclosure inspection results

The rationale for both passive and active disclosure of inspection results is threefold.

(i) Transparency. Without information on the inspection, one cannot assess the quality of the inspection or view the results of the inspection. This transparency is also present in other areas such as inspection results of the Inspectorate of Education and the Health Care Inspectorate.

(ii) Trust. By showing the results, the public can see what the NVWA is doing and therefore the public can build trust in the NVWA.

(iii) Increased compliance. Negative results of an inspection can lead to serious problems towards consumers or customers, such as liability claims from suppliers who expected to be supplied with products produced in compliance with the applicable quality standards and hygiene regulations). In this way active disclosure increases the pressure on FBOs to comply.

The current system

Opposed to other inspectorates in the Netherlands, the active disclosure by the NVWA is currently not provided for in a specific Act. So far, the mechanism laid down in the WOB has been used as the framework for disclosure of inspection results. Article 8 WOB enables the NVWA to actively disclose information, provided this is done is a clearly understandable way and offering interested parties in due time the opportunity to comment. As far as a request for information by any company or citizen is concerned, there are predefined grounds on which an administrative body cannot freely disclose information, being absolute and relative grounds. The absolute grounds are found to be of such importance that publication is interdicted, like confidential commercial information relating to the safety of the state or information containing personal data. The relative grounds relate for instance to privacy matters or to disproportional harm that could be created by publication. Such grounds have to be weighed against the interests of disclosure. In the current framework, the interested party can express a provisional opinion with respect to any intended publication by NVWA, which has to be dealt with before publication. This mechanism will disappear under the new system.

The new system

When the amendment of the Health Act will enter into force, the NVWA will not only have the option to actively disclose information, but will be obliged to do so. In the legal framework, the assessment of interests is already taken into account, which makes it unnecessary to do another assessment each time the NVWA decides to actively disclose information. In future, the option to express a provisional opinion by the NVWA will no longer be available. The only way to ensure that the information is not disclosed is starting summary proceedings before a civil court. If any interested party is doing so, NVWA will then be forced to suspend its decision to disclose information until the court decides on the matter. In case the NVWA will disclose the inspection report, the NVWA will provide the option for FBOs to provide a reaction to the inspection results, which will be disclosed together with the inspection results. In addition to the change applied to the Health Act, an underlying decree needs to specify more detailed rules on what information exactly needs to be published in what format. In the discussions on the amendment of the Health Act another amendment was added which ensures the underlying decree can only be amended with the approval of Dutch Parliament.

Current status of the amendment

On the 11th of October the House of Representatives of the Netherlands (Tweede Kamer) accepted the proposed changes to the Health Act and amended some parts. The Dutch Senate (Eerste Kamer) accepted the amendments without making any additional amendments on the 1th of November. However, the change of the Health Act has not yet entered into force and it is currently still unclear when the exact date of entry into force will be. Guestimates are hinting at June 2017, however the Ministry of Health Welfare and Sport is still working on the underlying decree on what information has to be published and in what format. There is a fair chance the amendment will only enter into force simultaneously with this underlying decree. In such case the entry into force of the changes to the Health Act will most likely be later than the guestimate mentioned above.

Situation in other EU countries and NVWA pilot

Other EU Member States already have a system of active disclosure of inspection results for restaurants in using a system of easily understandable designations or colours (Denmark and Ireland for instance). In those countries, the outcome of the inspection is presented at the entrance of the inspected restaurant, in order to give the public an overview of the level of compliance at first glance. For instance, a green colour or a happy face means that the restaurant is compliant and colours closer to red or a less happy face mean the place was less compliant. In the Netherlands, the NVWA launched a pilot for disclosure of inspection results for lunchrooms, which were disclosed via an app. This app subsequently displayed the results on a map. The map showed the lunchrooms in four different colours, depending on the level of compliance. The idea was to provide a quick overview of the lunchrooms and the level of compliance. However, the reaction of the minister of Health, Welfare and Sport to this format was negative due to interpretation issues, particularly interpretation of the colours. There are also lists of inspected products instead of inspected FBOs. The experience gained therewith and during the pilot will have to be evaluated in order to choose an acceptable form for the disclosure of over 200.000 inspections done each year in the Netherlands by the NVWA.

Criticism

The proposed changes to the Health Act have been much criticised. The active disclosure of the inspection results together with the imposed sanctions can be viewed as punitive sanction in addition to the sanction itself imposed based on the findings during the inspection. In the explanatory notes on the amendment of the Health Act, the government explains that active disclosure should not be perceived as a punitive sanction and therefore not a criminal charge in the sense of Art. 6 ECHR. In case the disclosure will be viewed as a punitive sanction, article 6 ECHR will be applicable, meaning the procedural safeguards embodied in this article will apply. Basically, the government states that the disclosure does not aim at punishing the inspected party, and therefore is not an additional sanction. However, the arguments provided by the government in the explanatory notes are not very convincing. Assuming the disclosure will lead to more transparency, consumers and customers will be aware of the non-compliance due to the disclosure. This disclosure can in turn decrease the trust in the non-compliant producer, which could mean a decline in sales or even liability claims from consumers or customers. It is not the fines imposed by the NVWA, but the disclosure of the inspection results, which leads to these (potential) damages of the producer, whom will not have had the chance to remedy the situation before it is out in the open. This is all the more important, as so far there is no evidence that such public disclosure indeed will lead to an increased level of compliance. Moreover, this situation does not seem to be in line with competition law, which constitutes the regular level playing field of any FBO, just like it is for manufacturers of medical devices or medicinal products. Therefore, competition law elements should in our opinion be an aspect of the legislation concerning disclosure. In the explanatory notes to the amendment, this aspect has not even been mentioned.

Conclusion

As a result of a change applied to the Dutch Health Act, the first steps towards active disclosure of inspection results from the NVWA have been initiated. The actual implementation thereof depends on the underlying decree, which is still under construction. This is why is not clear as of when the legal basis for active disclosure of NVWA inspection results will be operational. As of this moment however, FBOs will be subject to increased enforcement measures, without the effect thereof being necessarily positive. We will keep an eye out for you and report on any relevant development in this field, as they are likely to have an important impact for each FBO.

The author thanks Floris Kets for his contribution to this post.

Vitafoods revisited

Posted: May 31, 2016 Filed under: Food Comments Off on Vitafoods revisited This year marked the 20th anniversary of VitaFoods Europe. This is a global nutraceutical event, where the whole industry gathers to meet, talk, listen and do business. Axon Lawyers again participated in this event, which took place from 10 – 12 May in Geneva, by giving four presentations. Below, you will find a short wrap up of each of them as well as the slides belonging thereto.

This year marked the 20th anniversary of VitaFoods Europe. This is a global nutraceutical event, where the whole industry gathers to meet, talk, listen and do business. Axon Lawyers again participated in this event, which took place from 10 – 12 May in Geneva, by giving four presentations. Below, you will find a short wrap up of each of them as well as the slides belonging thereto.

B2C Communications in the functional food and nutraceutical sector

Each and any food business operator loves to communicate the benefits of its products, especially in the functional food and nutraceutical sector. However, a strict regulatory framework applies to such communication, which has been largely harmonized at EU level.

For instance, when using nutrition and health claims, one should make sure the authorized wording (or any permitted variation) is used, as well as that the conditions for use are met. Furthermore, one should know that regarding food for special medical purposes, the use of health claims is prohibited. It thereby does not make a difference whether the marketing is targeted at health care professionals or at consumers/patients. Finally, one should avoid making medical claims for food products, including functional foods.

The presentation shows that, based on the presentation of functional foods, it is not always easy to tell whether it is a food product or a medicinal product. Guidance is provided how to prevent a food product to qualify as medicinal products in order to prevent fines for unauthorized marketing of medicinal products.

Marketing functional food to children within the EU

The marketing of functional food to children requires intimate knowledge of the applicable legal framework, both at an EU and at a national level. This presentation starts with a bird’s eye view on the topic, based on the recommendations of the WHO on the responsible marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children.

Subsequently the EU framework embodied in the Regulations on Health & Nutrition Claims, Food Information to Consumers and Food for Special Groups is discussed, where concrete examples of authorised claims for specific products are discussed.

Finally, it is explained that in various Member States, self-regulatory bodies such as the Advertising Code Committee in the Netherlands and the Advertising Standards Agency in the UK, play an important role in the evaluation of marketing campaigns of functional food products targeted at children. Again, concrete examples are provided by way of guidance.

New EU Clinical Trials Regulation

The aim of the new EU Clinical Trials Regulation (‘CTR’), which is applicable from 28 May 2016, is to ensure that Member States base their assessment of an application for authorisation on identical criteria throughout the EU. Furthermore, it aims to create an environment that is favourable for conducting clinical trials in the EU with the highest standards for patient safety.

The CTR applies to all clinical trials conducted in the European Union. It does not apply to non-interventional studies. The CTR covers investigations in relation to humans intended to:

- discover or verify effects of one or more medicinal products;

- identify any adverse reactions to one or more medicinal product;

- study absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of one or more medicinal products to ascertain the safety or efficacy.

So, what is the relevance of the CTR for nutraceuticals, as only medicinal products are covered by the CTR? Although there is no legal definition of ‘nutraceutical’, the word was introduced in 1989 as a portmanteau of the words ‘nutrition’ and ‘pharmaceutical’. Thus, nutraceuticals blur the line between food and drugs and it is often difficult — by legal definition — to distinguish between nutrients, food additives, drugs and nutraceuticals. The presentation discusses relevant case law concerning the food/drug borderline and provides the highlights of the new CTR from that perspective.

Alternative sources of protein

Like last year, alternative proteins were all over Vitafoods. Reasons for the development of alternative sources of protein are easy to point out: health, sustainability and animal welfare. In October 2015, the WHO published a scientific report in which the following was concluded: ‘Consumption of processed meat increases colon cancer risk.’ In the Netherlands, the Dutch Health Council promotes a diet containing more plant based than animal derived proteins.

Eating less meat – and animal derived protein – is also better for the environment as the current production methods require too much natural resources. Last but not least, if meat consumption decreases this is positive for animal welfare. Not only because less animals are slaughtered, but the risk to outbreaks of diseases such as swine fever decreases. Therefore, today there are many alternatives to the consumption of meat.

In the presentation some alternative protein products, such as products containing algae, mushrooms or insects are discussed in the light of the new Novel Foods Regulation as food products may be qualified as “novel” and therefore require authorization under the EU Novel Foods Regulation.

All you wanted to know about organic food in the EU

Posted: January 26, 2016 Filed under: Enforcement, Food, organic Comments Off on All you wanted to know about organic food in the EU This contribution aims to provide you with a brief overview of the EU Organic legislation and recent developments. Being able to market products as ‘organic’ could be a plus for the food business operator (FBO) as the demand for sustainable production and organic food increases. This contribution focuses on the EU-system of organic certification of food products and will specifically look at the position of organic microalgae manufactured in the EU. Under the current legislative framework, these could not be marketed as such in the EU. This has changed since an interpretative note of the Commission of last summer. If you are an FBO interested in marketing organic microalgae, this for sure is of interest to you.

This contribution aims to provide you with a brief overview of the EU Organic legislation and recent developments. Being able to market products as ‘organic’ could be a plus for the food business operator (FBO) as the demand for sustainable production and organic food increases. This contribution focuses on the EU-system of organic certification of food products and will specifically look at the position of organic microalgae manufactured in the EU. Under the current legislative framework, these could not be marketed as such in the EU. This has changed since an interpretative note of the Commission of last summer. If you are an FBO interested in marketing organic microalgae, this for sure is of interest to you.

Organics Regulation – scope

First of all, what is ‘organic production’? According to recital 1 of the Organics Regulation organic production is: “(…) an overall system of farm management and food production that combines best environmental practices, a high level of biodiversity, the preservation of natural resources, the application of high animal welfare standards and a production method in line with the preference of certain consumers for products produced using natural substances and processes” (see also the definition in Article 2(a)).

What is covered by the Organics Regulation? Only agricultural plants, seaweed, livestock, aquaculture and animals are regulated under the Organics Regulation. For example, if an FBO wants to produce organic seaweed, all the processes have to be in compliance with the Organics Regulation. This approach is known as the ‘farm to fork approach’, which means every step in the production process throughout the supply chain has to comply with the Organics Regulation.

Organics Regulation – structure

The Organics Regulation has a layered structure. The following three layers of provisions can be found:

- General production rules (articles 1, 7 – 10), which apply to all forms of organic production.

- Production rules for different sectors (articles 11 – 21): general farm production rules and production rules for specific categories of products and production rules for processed feed and food.

- Detailed production rules (article 42).

If there are no production rules for the sector (layer 2), only the general production rules (layer 1) apply.

Organics certificate

Compliance with the Organics Regulation has to be demonstrated by obtaining certificates from a certification body. (See the following link for a list of competent certification bodies in different Member States). In the event a certification body audits the FBO marketing organic products and it encounters violations of the Organics Regulation, it can decide to block certain non-compliant batches of products pending an investigation. Depending on the outcome, the certification body can subsequently decide to withdraw the certificate. If the certificate is withdrawn, the FBO is no longer allowed to market the products as ‘organic’. In case of severe violations, the competent authority may impose a recall of the products. In the Netherlands, Skal Biocontrole is the designated Control Authority responsible for the inspection and certification of organic companies in the Netherlands, within the context of Regulations: (EC) Nr. 834/2007 (Organics Regulation), (EC) Nr. 889/2008 and (EC) Nr. 1235/2008 (import of organic products from third countries). Skal monitors the entire Dutch organic chain on behalf of the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs.

The EU organic logo

The EU logo is regulated in a separate Commission Regulation. The main objective of the European logo is to make organic products easier identifiable by the consumers. Furthermore it gives a visual identity to the organic farming sector and thus contributes to ensure overall coherence and a proper functioning of the internal market in this field. For practical information regarding the EU logo, see this link and this link.

Organic microalgae

Prior to July 2015, FBO’s could not obtain an organic certification for microalgae manufactured within the EU for the use in their food products. FBO’s from third countries (non-EU) could market their products in the EU based on either the import procedure as set out in Article 33 (2) (import from recognised third countries) or the import procedure laid down in Article 33 (3) of the Organics Regulation (import of products certified by recognised control bodies). The strange situation was created where ‘organic’ microalgae could only be imported into the EU and not be produced within the EU.

How come? All agricultural products were considered to fall within one of the different production rules for specific categories of products (layer 2) and microalgae for food production were not included. Furthermore, detailed EU production rules for microalgae were absent (layer 3). (Article 42 (2) Organics Regulation).

The Interpretative note of the European Commission (Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development) of July 2015 opened up the possibility for companies in both EU Member States and third countries to produce microalgae, which can be marketed as ‘organic’ and carry the EU organic logo. Both the existing production rules for plants (Article 12 Organics Regulation) and seaweed (Article 13 Organics Regulation) could be suitable for microalgae.

‘Until an implementing act adopted on the basis of Article 38 (of Regulation 834/2007) has clarified the situation, operators producing organic micro algae (except for use as feed for aquaculture) have therefore to comply with the general production rules, which apply to all forms of organic production (“layer 1”) and with the production rules for the sector of plants or seaweed (“layer 2”).’

The use of microalgae as feed for aquaculture is not covered in the Interpretative note, as microalgae as feed are already subject to the detailed production rules. The rules for the collection and farming of seaweed apply according to Article 6a of Commission Regulation (EC) No 889/2008.

The interpretation opens up the possibility to certify microalgae to be used as food (or as an ingredient in food) as being organic. When an implementing act will be published and enter into force is still unknown. A proposal for a new Regulation repealing the Organics Regulation has been published. On 5 November 2015 a report from the Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development on the proposal was published, introducing 402 amendments. The current status of the proposal is available through this link.

Aside from enforcement by a national control authority in case of non-compliance with the Organics legislation, consumers and other interested parties often also have the possibility to lodge a complaint relating to advertising of organic products. However, advertising of (organic) products is a topic to be covered in another contribution on Food Health Legal. Stay tuned!

180 fold higher fines in Dutch Commodities Act

Posted: September 14, 2015 Filed under: Enforcement, Food | Tags: Commodities Act, enforcement, fines, NVWA, Warenwet Comments Off on 180 fold higher fines in Dutch Commodities ActOn 11 September 2015 new legislation amending the current Commodities Act (in Dutch: Warenwet), partly entered into force. Under the new legislation the maximum administrative fine to be imposed on Food Business Operators (hereinafter: ‘FBO’s’) by the Dutch Food Safety Authority (NVWA) is increased dramatically compared to the prior maximum fine. The Dutch legislator has clearly increased existing fines to make them stronger and more effective to increase compliance with food safety regulations. The NVWA has more teeth, but will it bite?

The rationale behind the increased fines

A reason to increase the maximum fines can also be found in the battle against food fraud in general. Until recently the NVWA could impose a fine on an FBO on the basis of Article 32 of the Commodities Act. The maximum fine was set at € 4.500. According to its latest annual report, the NVWA imposed 2808 fines on FBO’s in 2014. The average amount of a fine was € 1.206,– and the total amount of imposed fines was € 3.413.893,–. Considering the costs of compliance with hygiene and administration standards, these penalties are merely peanuts for the average FBO and do not have the desired effect of contributing to compliant behavior as is confirmed by the statement further down in this post.

Fines linked to system under Dutch Penal Code

Fines in other areas such as data protection law are also subject to revision and they will both increase and expand (meaning an increased number of provisions will be subject to potential fines in case of non-compliance and those fines tend to increase as well). With a political climate both in the EU and in the Netherlands that leans towards stronger enforcement instruments, it was just a matter of time before the fines under the Commodities Act would be increased. The Dutch legislator seems to try to harmonize the several fines in different legal acts by referring to the categories of fines specified in the Dutch Penal Code. These categories are linked to the severity of the violation. The first category is the lowest and the sixth category the highest. The maximum fines are now set at the maximum of the sixth category: € 810.000,– (or 10% of the annual turnover). This means a 180 fold higher maximum fine!

In relation to the increase of administrative fines politician Sjoera Dikkers (Dutch Labour Party – PVDA) stated: “it is clear that a fine of € 4.500,– is cheaper for practically every company, then acting in compliance with hygiene practices in the Netherlands. For a fine of € 81.000,– this can be similar for big companies, depending on the nature of the infringement. That is why we would like to further increase the maximum penalty to the sixth category. This is the only way to scare companies enough to make sure they comply with hygiene requirements.”

The exact amount of the fine will have to be proportionate and therefore depend on factors such as the number of employees, the degree of culpability, the severity of the violation and/or the turnover of an FBO. The NVWA has to assess all individual circumstances in order to establish the amount of the fine.

Final thoughts

Although relatively low fines indeed might give rise to profit for FBO’s from non-compliance and fraudulent behavior, drastically increasing the fines could have a downside for both the NVWA and the FBO’s. Imposing higher fines requires more effort and expertise from the NVWA. For fines that exceed the amount of € 340,– additional procedural requirements, similar to criminal law, have to be met by the NVWA. For FBO’s a high fine could indeed have a significant impact and even potentially mean bankruptcy. As we have seen in Dutch cases relating to the horsemeat crisis, the NVWA can impose the execution of a recall that can lead to bankruptcy. We will keep you informed on how this potential powerful enforcement instrument of high fines in the hands of the NVWA is handled in practice and dealt with in court. Hopefully, this will serve FBO’s in establishing what should be done to avoid or annul the decision of the NVWA to impose such fines, which is a part of our active practice.

The author is grateful to Floris Kets, trainee at Axon Lawyers, for his valuable contribution to this post.

New legislation: COOL for unprocessed meats

Posted: April 12, 2015 Filed under: Food | Tags: COOL, labelling, meat, origin Comments Off on New legislation: COOL for unprocessed meats In a previous post from January last year I wrote about country of origin labelling (COOL). I mentioned that the Commission was expected to adopt implementing rules on mandatory COOL for unprocessed meat of sheep, goat, pig and poultry, based on the Food Information to Consumers Regulation. A nice infographic about the new EU food labelling rules can be found here.

In a previous post from January last year I wrote about country of origin labelling (COOL). I mentioned that the Commission was expected to adopt implementing rules on mandatory COOL for unprocessed meat of sheep, goat, pig and poultry, based on the Food Information to Consumers Regulation. A nice infographic about the new EU food labelling rules can be found here.

And now there is ‘COOL’ news: rules on origin labelling for meat apply from 1 April 2015. Which rules? The Commission adopted Regulation 1337/2013 on the indication of the country of origin or place of provenance for fresh chilled and frozen meat of swine, sheep, goats and poultry.

Background and scope

As from 1 April 2015 no packaged unprocessed meat product from abovementioned animals may be lawfully placed on the market in the European Union without a label indicating where the animal was reared and slaughtered. An exception applies to meat that was lawfully placed on the Union market before 1 April 2015. This may be sold until the stocks are exhausted, provided of course that the best before date/use by is not exceeded.

The European COOL rules do not apply to processed meats. In December 2013 the European Commission published a report concerning mandatory country of origin labelling (COOL) for meat as an ingredient. The overall conclusion of the report is that consumer interest in COOL is strong, but this is not reflected in the willingness pay for the extra costs for FBOs and an additional administrative burden. Read this post if you want to recall the discussion on the December 2013 report. Click here for the response (in Dutch) from the Dutch Food Industry Federation (FNLI) on the resolution and here for an article on this topic on the website of EurActiv. Until now, COOL has not been extended to processed meats, however this may change. In this resolution from February 2015, the European Parliament urges the Commission to follow up its report with legislative proposals making the indication of the origin of meat in processed foods mandatory. It is expected that this will ensure greater transparency throughout the food chain and it will rebuild consumer confidence in the wake of the 2013 horsemeat scandal, and other food fraud cases. This seems contrary to the outcome of the report in terms of feasibility as COOL for processed meats means higher costs for the industry and an increased administrative burden.

Now let’s have a look at the new rules. What is meant with ‘country of origin’ and what information should be placed on the label? Continue reading to find out!

Labelling rules

The core provision of the new Regulation is Article 5, which lays down the COOL rules for the meats covered by the Regulation. Either the indication (i) ‘origin’, (ii) ‘reared in’ + ‘slaughtered in’, or (iii) a list of different indications should be placed on the label according to Article 5.

What is meant with ‘country of origin’ for meat products?

Recital 3 of Regulation 1337/2013 refers to the concept as set out in Articles 23 to 26 of Council Regulation 2913/92 (Customs Code). For meat products the country of origin means the country in which the animal was born, reared and slaughtered. Only in this situation the following indication may be placed on the label as far as the food business operator is able to prove the correctness of the statement to the competent authority:

- ‘Origin: (name of Member State or third country)’

But what if the meat comes from animals, which were born, reared and slaughtered in different countries? In that case in indication of the country (Member State or third country) where the animal was reared and the country where the animal was slaughtered have to be specified on the label.

‘Reared in’

Article 5 of the Regulation gives specific criteria to determine the correct indication for the country where the animal is ‘reared in’ related to the rearing period of the animal in a country. If the specified rearing period is not attained in any country the label must show one of the following indications:

- ‘Reared in: several Member States’

- ‘Reared in: several non-EU countries’

- ‘Reared in: several EU and non-EU countries’

- ‘Reared in: (list of Member States or third countries where the animal was reared)’

The last option may only be used if the FBO is able to prove this to the competent authority.

‘Slaughtered in’

The Member State or third country in which the slaughter of the animal took place has to be indicated as follows:

- ‘Slaughtered in: (name of the Member State or third country)’

If pieces of meat, of the same or different species, are packed together and correspond to different labelling indications, the label has to indicate the list of relevant countries for each species (see Article 5(3)).

Furthermore, the batch code identifying the meat supplied to the consumer or mass caterer should be placed on the label.

A little extra : COOL in the U.S.

: COOL in the U.S.

If you are a FBO operating both in the EU and the US you might be interested in COOL in the U.S. Like Europe, the U.S. COOL statute defines multiple origins for muscle cuts of meat, depending on where the animal was born, raised and slaughtered. This is pretty much in line with Europe, which defines “born, reared and slaughtered” as the origins that must be placed on the label. Do you want to learn more about COOL in the US and how the new EU rules are perceived in the U.S.? Here is an article.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Agricultural Marketing Service has published a practical COOL labelling guide for the industry with specific examples of appropriate COOL language for the U.S. market. You can find it here.

Cool with COOL?

What is the potential impact of the new rules on your business? With an increased complexity of the label this is likely to increase the costs for compliance. Consumers will receive extra information, but will they see this as an improvement? With regards to food safety, the Regulation prescribes the use of an identification and registration system to ensure traceability (Article 3). The system has to particularly record the arrival at and the departure of animals, carcasses or cuts from the establishment of the FBO. Also a correlation between arrivals and departures has to be ensured. Aside the mislabelling issue, the horsemeat scandal clearly showed that the current traceability systems are not adequate in case of incidents. More detailed rules on traceability are aimed to contribute to food safety and protection of food safety is also an important interest for the food industry. Compliance is serious business as non-compliance can lead to administrative sanctions. Furthermore, fraudulent labelling constitutes a criminal offence and an offender can be prosecuted under criminal law. This is what happened to Dutch meat trader Selten. Last week he has been sentenced to 2.5 years in prison. According to the court he is guilty of forgery. He has sold horsemeat as beef. Click here for the newsitem (in Dutch).

Marketing insects as food products – a regulatory update

Posted: November 27, 2014 Filed under: Food, novel food Comments Off on Marketing insects as food products – a regulatory update Do bugs have a place on your dinner plate other than the fly that lands on it or the caterpillar that accidently ended up in your dish, as it happened to live in the cauliflower you prepared for dinner? If you live in Europe you are likely to answer this question with ‘no’ and you might even have a slightly disgusted look on your face right now…

Do bugs have a place on your dinner plate other than the fly that lands on it or the caterpillar that accidently ended up in your dish, as it happened to live in the cauliflower you prepared for dinner? If you live in Europe you are likely to answer this question with ‘no’ and you might even have a slightly disgusted look on your face right now…

FAO and European Commission on insects

In other parts of the world certain insects are part of people’s diet and are sometimes even considered as a delicate and exclusive bite. The call to expand the consumption of edible insects worldwide recently became louder. According to the UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), insects can potentially help solving the increasing demand for animal protein. In 2013 FAO published the report ‘Edible insects’ and in May 2014 the first international conference ‘Insects for food and feed‘ was organized in the Netherlands in collaboration between Wageningen University and FAO. This video provides a summary of the conference. Furthermore, Wageningen University announced the launch of the first scientific journal focussing on this topic in 2015. On 27 November 2013 the Director General for Health and Consumers mentioned edible insects as an interesting alternative source of protein in her speech:

‘Looking to the future, feeding a growing world population will inevitably increase pressure on already limited resources – land, oceans, water and energy. The development of alternative sources of protein will no doubt grow in importance and significance to meet the future protein demand. Such sources include cultured meat, seaweed, beans, fungi and, of course, insects. The greater use of insects is an interesting alternative both for human consumption and animal feed, given the prospect of high protein yields with low environmental impacts.’

Are edible insects Novel Foods?

During the abovementioned conference it became clear that there was an urgent need to develop legislation on edible insects to give the food and feed industry clear guidance on the requirements they have to meet. This discussion paper provides a look at the regulatory frameworks influencing insects as food and feed at international, regional and national levels. This paper, however, is not exhaustive. The European Commission has asked EFSA to deliver a scientific opinion on the risks of insect consumption, but this opinion is expected in 2015 at the earliest. Another question is whether insects should be considered Novel Foods covered by EC Regulation 258/97. According to this Regulation, Novel Foods require pre-market approval in the EU (Do you want to read more about Novel Foods? Check this, this and this post). At this moment the European Commission has not explicitly decided on whether insects should be considered Novel Foods or not. Until a clear position and a harmonization of the novel food status of insects at European level have been adopted, some Member States decide to apply their own ‘rules’ for the placing on the market of insects intended for human consumption.

Belgium

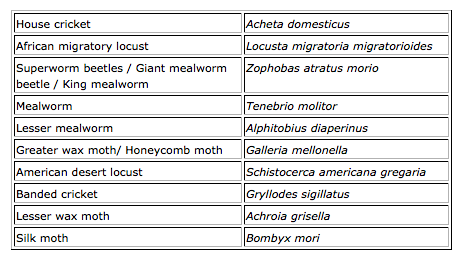

In Belgium the placing on the market of the species included in the table below is tolerated, provided that the requirements of food legislation are met, especially and among others the application of good hygiene practices, traceability, compulsory notification, labelling and organisation of a self-checking system based on the HACCP principles. This tolerance does not apply to food ingredients isolated from insects, such as protein isolates.

Also France and the United Kingdom seem to tolerate the sale of edible insects in their countries. If you have any additional information from your country or region to include in this post, you are cordially invited to share this with us through info@axonlawyers.com.

The Netherlands

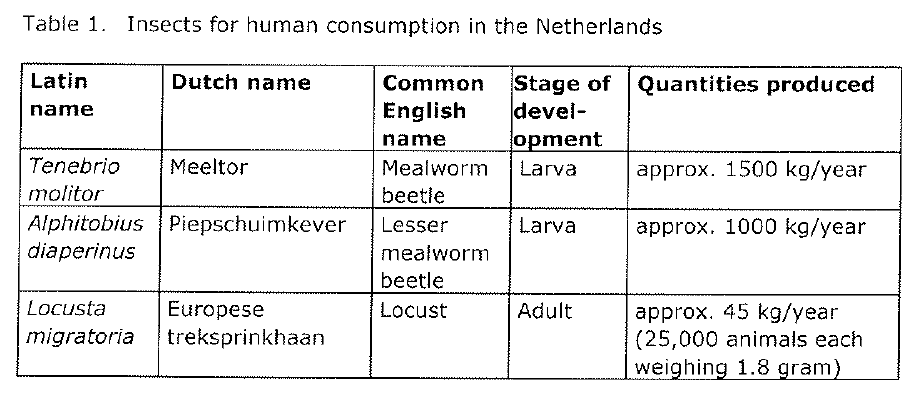

On 15 October 2014 the Dutch Office for Risk Assessment & Research (in Dutch ‘Bureau Risicobeoordeling & onderzoeksprogrammering‘, herinafter: ‘BuRO’) published their advisory report to the Inspector-General of the Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (in Dutch: ‘NVWA’) and the Dutch Ministers of Health Welfare and Sport and Agriculture. According to this report the following insects are currently produced and sold in the Netherlands.

The NVWA asked to assess the chemical, microbiological and parasitological risks of consuming heat-treated and non-heat-treated insects. The risk assessment was limited to the three species mentioned in table 1 above. BuRO recommends the Ministers to treat those insects as foods in the meaning of the General Food Law (Regulation 178/2002) that are required to comply with the hygiene regulations (Regulations 852/2004 and 853/2004) and all other food-related legislation. Those insects are not treated as Novel Foods in the Netherlands.

With regards to food safety, BuRO recommends the NVWA to use the following minimum requirements for rearing facilities:

- Products introduced to the market must have been heated to reduce microbiological risks. The hygiene criteria for processing of raw materials in meat preparations should be used.

- Food safety criteria for insect products:

– Salmonella: absent in 10 grams;

– L. monocytogenes: <100 CFU/g;

– B. cereus, C. perfringens, S. aureus and Campylobacter spp: criteria stated in the Decree on Preparation of Foodstuffs.

- Shelf life of 52 weeks must be demonstrated.

In the Netherlands, the Laboratory of Entomology from Wageningen University is involved in research on edible insects. Scientists Arnold van Huis and Marcel Dicke and cooking instructor Henk van Gurp even published a cookbook: the Insect Cookbook. Click here, here and here for video’s from these scientists on eating insects. More and more supermarkets in the Netherlands sell edible insects. Online it is possible to order various kinds of edible insects from around the world, which are not included in the lists above. NVWA does not seem to focus on enforcement in this area as long as food safety is not at stake.

A slaughterhouse for insects?

The question has been raised whether Regulations regarding to slaughtering animals are also applicable to the killing of insects for consumption. Regulation 1099/2009 on the protection of animals at the time of killing covers the killing of animals bred or kept for the production of food, wool, skin, fur or other products as well as the killing of animals for the purpose of depopulation and for related operations. So far, the Regulation seems to apply to the killing of insects. However, the Regulation defines ‘animals’ as ‘any vertebrate animal, excluding reptiles and amphibians’. Insects are invertebrates, which have an exoskeleton and don’t have a spinal column. This means that insects are outside the scope of this Regulation.

Final thoughts

Novel Food or not, despite the lack of (legal) guidance and certainty regarding the regulatory status of insects on EU level, it is clear that the attitude towards the use of insects for food and feed is positive. Therefore, some Member States take action to allow the marketing of insects as food in their country until a clear position has been reached at European level. When EFSA publishes their report and the European Commission takes its position regarding the use of insects for food and feed, you will read it here or get informed through Twitter: @FoodHealthLegal.

Axon seminar Functional & Medical Foods

Posted: August 15, 2014 Filed under: event, Food, Food Supplements, Health claims, Information, novel food, Nutrition claims Comments Off on Axon seminar Functional & Medical Foods On 24 September 2014 our firm organizes a seminar addressing the developments in Functional and Medical Foods. Where? Next door to our office in Pakhuis de Zwijger.

On 24 September 2014 our firm organizes a seminar addressing the developments in Functional and Medical Foods. Where? Next door to our office in Pakhuis de Zwijger.

Functional foods

The Institute of Medicine has designated functional food as “any food or food ingredient that provides a health benefit beyond its nutritional benefit”. Functional foods comprise food supplements, probiotics and other foods having a beneficial effect on human health, which is often advertised by health or nutrition claims as using those claims in connection with this type of foods is very attractive from a marketing point of view.

Medical foods

Functional foods are just one step away from medical foods, catering for particular nutritional needs that regular foods do not supply. Contrary to functional foods, medical foods are highly regulated. Furthermore, both types of food are subject to specific legislation regarding health and nutrition claims as well as regarding food information to be provided to consumers.

The regulatory requirements for health and nutrition claims offer a chance and a challenge. Also, as of 13 December 2014, all food business operators have to comply with very strict, new information requirements on the basis of the Regulation on Food Information to Consumers. To what extent does this regulation help the final consumer to make healthy choices and how does this impact the entrepeneur? Our seminar will address these issues and provides practical guidance on solutions. Speakers are: Bernd Mussler (Innovation Project Manager at DSM), Ruud Albers (CEO at Nutrileads) and us (Karin Verzijden and Sofie van der Meulen).

A few spots left!

We still have a few spots left! Attendance is free and you are welcome to bring along your colleagues. More info? Check the invitation on our website. For registration, please send an e-mail to info@axonlawyers.com with your name, the names of colleagues you would like to register and contact information. Questions? Contact our office manager Marjon Kuijs at marjon.kuijs@axonlawyers.com or +31 (0) 88 650 6500.

Looking forward to see you there!

Missed our seminar? Download our slides!

The slides of our seminar on medical and functional foods can be found here and also via our SlideShare account.

Annual Conference on European Food Law

Posted: May 8, 2014 Filed under: Food, novel food | Tags: animal, cloning, food, novel Leave a comment »Early this week the Academy of European Law’s Annual Conference on Food Law took place on 5 and 6 May in Trier and offered a unique opportunity to receive an analysis of recent legislation, case law and ongoing policy developments in the field of food law (for an overview of the full programme, click here).

Key topics that were discussed during the conference:

- New EU rules on articles treated with biocidal products

- The Commission’s proposals on animal cloning and novel food

- Recent case law of the CJEU

- The legislative package for healthier animals and plants for a safer food chain: smarter rules for safer food

- The harmonisation of food standards and food safety measures within the framework of the World Trade Organisation

My talk discussed the Commission’s proposals on animal cloning and novel food. Novel foods are all foods that were not used for human consumption to a significant degree within the EU prior to 15 May 1997. An example is juice of an exotic fruit: noni juice. Currently novel foods are covered by Regulations 258/97 and 1852/2001. Novel foods, including food from cloned animals, are subject to pre-market approval, but obtaining market access under the current regime is a lengthy process that can take up 3 to 6 years. Therefore, between 2008 and 2011, a new proposal for a Novel Foods Regulation was published, but this proposal has never been adopted as concilliation failed in March 2011. One of the sensitive issues was food from cloned animals. In order to find a solution for this issue, the latest proposal for a Regulation on Novel Foods no longer covers such food.

Food from animal clones and animal cloning are now covered in two separate proposals:

(1) Directive on the cloning of animals of various species kept and reproduced for farming purposes

(2) Directive on the placing on the market of food from animal clones

These proposals will result in:

- A temporary ban on the imports of animal clones and a prohibition to place food from animal clones on the market

- A temporary ban on the use of cloning technique in the EU for farm animals

Download my slides and…

Do you want to learn more about the proposals? You can download my slides here! See you at the next ERA Annual Conference on European Food Law?

Untraceable = unsafe?

Posted: February 22, 2014 Filed under: Enforcement, Food | Tags: enforcement, horsemeat, recall, safety Leave a comment » Dutch slaughterhouse Van Hattem suffering severe blow

Dutch slaughterhouse Van Hattem suffering severe blow

This week the Trade and Industry Appeals Tribunal, (in Dutch: College van Beroep voor het bedrijfsleven) rendered its judgment (interim injunction) in the lawsuit that was filed by slaughterhouse annex meat processing company Van Hattem Vlees B.V. against an administrative enforcement decision from the State Secretary for Economic Affairs.

Recall large amount of meat

In her decision, the State Secretary imposed an administrative order to recall all meat produced or processed by Van Hattem between 1 January 2012 and 23 January 2014 (approximately 28.000 tons of meat). The request to suspend the order to execute the recall was rejected by the Court. Why? First of all, horsemeat was detected by the Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (NVWA) in a lot of meat that was solely labelled as beef. This is a matter of fraudulent labelling and not of food safety (see also my other articles concerning labelling and the horsemeat scandal here and here). As the investigation continued, Van Hattem failed to clarify the origin and destination of several slaughtered horses. Read below how this is relevant for to the safety of the meat.

Horse passport

Horses in the EU require a passport for identification according to Regulation 504/2008. The slaughterhouse has to check whether a horse is indicated for slaughter in its passport. If so, an official veterinarian has to perform an inspection of the live horse. Without a passport and inspection the horsemeat can be declared unfit for human consumption. Also, information in the passport such as drug use, can result in disapproval of the intended slaughter for human consumption as residues of veterinary drugs can pose a health risk for humans.

The risk of dark horses

Van Hattem was not able to fully trace the processed meat and the company’s administration showed an unclear discrepancy between the amounts of received meat and the amounts that left the company. More horses were slaughtered than were inspected and approved for slaughter. The processing of (now) unidentifiable “dark” horses poses the risk that horsemeat unfit for human consumption ends up in food products for consumers, putting consumer health in jeopardy. The placing on the market of unsafe food is illegal according to Article 14 of Regulation 178/2002 (The General Food Law).

Was the meat in the case of Van Hattem indeed unsafe? Even though there was no evidence of unsafe food, the risk of unsafe food was sufficiently substantiated to consider the meat unsafe. Thereby an order to execute a recall was triggered based on Articles 17, 18 and 19 of the General Food Law (Article 14 is not mentioned by the Court). The Court does not place its bets on a dark horse. The Court ruled that although the order to execute a recall has a far-reaching impact on the business of Van Hattem, the order is proportionate given the circumstances.

Comparable decision re. Selten

In the ruling re. Van Hattem, the Court explained the relation between the specific circumstances and the risk of unsafe food. In a comparable judgment resulting in a recall of horsemeat, no such risk was pertinent per se. The case related to meat processing company Willy Selten B.V. The rationale for seizure in that case pertained to the facts that horsemeat was detected, which was not declared on the label and Selten’s business records could not be used to trace and identify the meat. The requested interim injuctions by this company were rejected twice (see here and here). But was there any indication that processed meat that was placed on the market was unsafe? In fact, there were not. The reasoning of the Court basically came down to stating that because the meat was untraceable, the meat was unsafe. The Court further added that it was almost certain that the veterinary drug phenylbutazone was present in one of the seized lots. But the presence of this drug poses no food safety issues according this joint statement from the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). See also this press release from the European Commission concerning phenylbutazone. In it’s conclusion, the Court in the Selten case referred to Article 14(6) of the General Food Law which reads as follows:

‘Where any food which is unsafe is part of a batch, lot or consignment of food of the same class or description, it shall be presumed that all the food in that batch, lot or consignment is also unsafe, unless following a detailed assessment there is no evidence that the rest of the batch, lot or consignment is unsafe.’

As set out above, in this case there was no indication of unsafe food, therefore the imposed order should have been lifted. It seems a tall order to base the order on Article 14 General Food Law as the requirement of unsafe food has not been fulfilled. In my opinion, the correct reasoning in this matter would have been as follows:

Untraceable = ?

Criminal prosecution

In the judgment re. Van Hattem, the Court mentions that the instrument of an order to execute recall has a far-reaching impact on the business of the company involved. In the case re. Selten, the company went bankrupt. Therefore, the instrument of recall should only be used if food safety is at stake. Especially in the case re. Selten, I have the impression that the administrative instrument of a recall is abused to punish the offenders and that the emotion and demand for action of consumers played a role here (I wonder if consumers would have responded differently if it were not horse but chicken that was mixed with beef, but that’s quite a different story). But the Court did have an escape. Without evidence of unsafe food, fraudulent labelling still constitutes a criminal offence and the offenders can be prosecuted for forgery under criminal law.

Developments

The supply chain of processed meats is complex and lengthy. The existing EU traceability systems are not adequate to pass on origin information, because the legislation is primarily based on the need to ensure food safety. The horsemeat scandal clearly showed this. The debate concerning COOL might therefore give rise to changes to the traceability systems and the proposed new Regulation on Official Controls aims to strengthen the enforcement of health and safety standards. Further, supermarkets in the Netherlands have announced to tighten the required certification for all suppliers. At end of this month the Global Food Safety Initiative will launch the module “Food Fraud”. The Dutch food industry federation (FNLI) welcomes this initiative and urges its members to add this module in their food safety system.