Posted: September 25, 2018 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Food, Information, novel food |

“The FDA knows just how vital it is to ensure the safety of our nation’s food supply and the critical role science-based, modern regulatory frameworks are to fostering innovation. Recent advances in animal cell cultured food products present many important and timely technical and regulatory considerations for the FDA and our partners at USDA,” said Commissioner Gottlieb. “We look forward to the opportunity to hold a meeting with our USDA colleagues as part of an open public dialogue regarding these products.”

“The FDA knows just how vital it is to ensure the safety of our nation’s food supply and the critical role science-based, modern regulatory frameworks are to fostering innovation. Recent advances in animal cell cultured food products present many important and timely technical and regulatory considerations for the FDA and our partners at USDA,” said Commissioner Gottlieb. “We look forward to the opportunity to hold a meeting with our USDA colleagues as part of an open public dialogue regarding these products.”

Harvard Law School

This is a new quote taken from the website of the FDA, regarding a joint FDA – USDA meeting on animal cell culture technology on 23 and 24 October 2018 in Washington. Securing regulatory clearance is pivotal for market access of this type of products, which used to be often referred to as “clean meat,” “cell-based meat,” or “lab-grown meat,” depending on whom you would ask. Since the Good Food Conference early September, there seems to be consensus to retain the term “cell-based meat”. To date, there is however no consensus on the appropriate US regulatory framework for these products, which is why this new meeting has been set. In particular, it is not clear which federal regulatory agency – the FDA or USDA or both – has jurisdiction over these products with respect to labeling, safety and inspections, or whether these products will meet regulatory definitions relating to “meat” and “poultry.” Harvard Law School, in particular its representatives from the Food Law and Animal Law groups, recognizes the potential benefits of clean meat and other cellular agriculture products. Therefore, on 9 and 10 August 2018, the school organized the Clean Meat Regulatory Roundtable in order to address the regulatory concerns surrounding this new industry. Further to an earlier post on this subject, this is take #2 on the Harvard initiative, reporting a selection of topics discussed at that table. Also a comparison with the EU regulatory framework shall be made where relevant.

Participants Regulatory Round Table and Ruled of Play

In order to let the discussion benefit from as many perspectives as possible, representatives from academia, the industry and from interest groups participated in Harvard’s Clean Meat Regulatory Roundtable. Obviously, the meeting included a number of representatives from Harvard Law School. Furthermore, the nonprofit organizations Good Food Instituteand the Animal League Defense Fund were present. The participating companies were Mosa Meat and Fork & Goode (both working on clean meat), as well as Blue Nalu (working on clean fish). From the investor side, Stray Dog Capital was represented and from the industry DuPont provided its input. Finally, a number of US lawyers participated, including Deepti Kulkarni from Sidley Austin LLP. I myself shared my insights on this topic from an EU perspective. To encourage openness and the sharing of information, all participants agreed to a Chatham House Rules + regime, meaning that the topics discussed during the meeting could be reported, but the participants were not at liberty to identify, either explicitly or implicitly, the identity of the speaker or his or her affiliation.

Cooperation on optimal regulatory pathway?

Amongst the participants, there was a common concern that if one party rushes unprepared to the market, ignoring the appropriate regulatory pathways, that could poison the well for the entire cellular agricultural industry. It was therefore discussed to what extent the cellular agriculture industry could cooperate regulatory-wise. It became clear that even though clean meat products share certain characteristics, finished products could be quite different in terms of formulation, composition, or other product characteristics. Nonetheless, general principles for assessing safety and product identity could be established under existing regulatory authorities. Such principles could for instance involve considerations relating to substances used in the production of clean meat, including scaffolds, growth factors, and cell culture medium or potential variations in the production process. In addition, it was discussed whether common interests could be effectively promoted through a trade association or industry group. The participants discussed various options, including setting up a dedicated association and connecting with existing organizations such as BIO.

Agency Jurisdiction

Contrary to the situation in the EU, where the European Commission is the one stop shop for obtaining a Novel Foods authorization, in the US foods can be subject to regulatory oversight by multiple federal and state agencies. It is has not yet been decided which agency has jurisdiction over these products, or whether the products are subject to dual oversight. In general, USDA regulates meat and poultry, including the inspection of establishments that slaughter such animals or otherwise process meat and poultry products. FDA generally regulates all other food, including fish and certain other meat and poultry products, such as bison, rabbits, and wild turkeys and ducks. In addition, FDA regulates new ingredients (as “food additives”) used in the production of foods under its jurisdiction, as well as new ingredients used in meat and poultry products that otherwise would be subject to USDA oversight.

Continuous inspections?

Meat and poultry products subject to USDA jurisdiction generally require “continuous” or daily inspection, depending upon the nature and frequency of operations. Because the production of clean meat does not involve slaughtering animals and such products would not be derived from slaughtered animals, there are open questions regarding the applicability of USDA’s inspection regime. This is even more so when clean meat products are not “harvested” daily, but on a batch-based basis. Arguments, nonetheless, can be made in favor of USDA jurisdiction with respect to “processing” inspections and other in-market activities, as well as product labeling. Nevertheless, at the Roundtable, there seemed to be a slight preference for FDA jurisdiction both pre-market and in-market.

Traditional meat industry’s concern of level playing field

The views of the traditional meat industry are somewhat fractured with respect to the clean meat industry. Some have taken considerable stakes in clean meat ventures (consider the investments of both Tyson and Cargill in Memphis Meats), particularly industry segments more closely involved with raising livestock are less supportive. For example, the US Cattleman’s Association submitted a petition to the USDA in February this year, asking it to establish labeling requirements that would prohibit clean meat from using terms like “meat” or “beef” in product labeling. Most trade groups representing the traditional meat industry have called for a “level playing field” where clean meat products would be subject to some level of USDA inspection. In general, all participants at the Harvard Panel agreed that a discussion with the traditional meat industry on how clean meat should be regulated would be critical. Notably, clean meat producer Memphis Meats and the North American Meat Institute, a trade group that represents the largest meat producers in the U.S. recently issued a joint letter to the White House outlining a regulatory regime under both FDA and USDA, and calling for a combined meeting involving the White House, USDA, FDA, and representatives of the traditional meat and clean meat industries.

Pre-market evaluation

Even if the FDA were to have some level of jurisdiction over clean meat products, it is still not completely clear what data would need to be submitted to demonstrate safety. One of the participants opined that, unlike a food additive approval, neither a GRAS determination, nor an FDA consultation (see here for an example of a consultation procedure on plant based products) would result in an affirmative regulatory approval. Some were of the opinion that a regulatory opinion short of approval would not benefit the clean meat industry, particularly in the eyes of the public. By contrast, others particularly those familiar with the GRAS process and the requisite scientific information needed to demonstrate safety disagreed with the position that a GRAS determination would not be rigorous or otherwise appropriate. The participants then discussed that a potential hybrid model that followed the GRAS approach, but also involved a third-party safety opinion could be an option. As to the required data, it was discussed what would be the “ingredient” that would be assessed by the competent government agency. The substances used in the culture of clean meat products most likely are of relevance, even if they may qualify as mere processing aids that normally only remain as residues in the final product without technical function. One participant mentioned such substances could easily be tested in separate toxicology studies, to which reference could be made during the pre-market evaluation (US) or in the application for a Novel Foods authorization (EU).

EU market entry of Novel Foods

Compared to the US, the regulatory pathway for clean meat products in the European Union is relatively clear. Under the new Novel Foods Regulation (effective as per 1 January 2018), an application for an authorization of a Novel Food should be made with the European Commission, who will subsequently distribute this to all EU Member States. The application should in the first place contain a detailed description of the product for which an authorization is sought, as well as of its production process. Furthermore, a proposal for the purported conditions of use should be handed in and a labelling proposal that does not mislead the consumer. Last but not least, the applicant should provide scientific evidence, demonstrating the purported Novel Food does not pose a safety risk. For this purpose, tox studies that comply with Good Laboratory Practices are mandatory, as is an evaluation of the total safety strategy. This should be based on proposed uses and likely exposure, with justification to include or exclude certain studies in order to prevent cherry picking. Upon receipt of the Novel Food application, it is anticipated that the Commission will request a safety opinion from EFSA, who will evaluate, amongst other things, if the Novel Food concerned is as safe as food from a comparable food category already placed on the EU market. The EFSA evaluation should not exceed a 9 months term. Within 7 months after receipt of a positive safety opinion, the Commission should publish its implementing act, which will result in the inclusion of the approved Novel Food in the Union List. The single open end in this procedure is the term for response for the Member States, which in the former Novel Food Regulation used to be 60 days. Surprisingly enough, this term is not mentioned in the new Novel Food Regulation that applies as of 1 January this year. However, there are no reasons to believe this should be any different under the current Novel Foods Regulation.

In-Market Safety

In order to inspire consumer confidence in clean meat products, the participants discussed how to best ensure the products’ short and long-term safety, particularly against the backdrop of public fear and aversion to genetically modified foods. Despite the assurance that FDA provided regarding the safety of these foods, many consumers remain fearful or otherwise suspicious of such foods. The participants agreed that steps should be taken to avoid a similar unwarranted aversion to clean meat products, including transparency initiatives and consumer education. In this framework, it was suggested that the clean meat industry could pro-actively develop its own HACCP program, provided that the industry could reach agreement on what would be the best way to identify the hazards and applicable critical control points. To this respect, it is relevant that both FDA and USDA have HACCP regulations and have identified hazards of chemical, biological and physical nature that might be applicable to this new sector.

Labeling, marketing, product identity

Vivid discussions took place regarding whether or not clean meat or fish products could be called “meat” or “fish” respectively. Whereas some argued: “Meat is what it is, so meat it should be called”, others considered the actual name less important. Most likely, we will not see the plain term “meat” on product packaging, but rather “ground beef,” “meatballs,” or “chicken tenders”. Some participants cautioned that, in order for products to be labeled with such product-specified terms, they generally would have to meet the general definitions for “meat” or “poultry,” unless the labeling adequately described or qualified the product. For product placement, it is of relevance whether the clean meat products belong to the “meat department” or somewhere else, though several participants clarified that such placement is decided by agreements with retailers, rather than by regulatory oversight. All participants agreed that a so-called qualifier that would explain the exact nature of the product, could benefit the industry. Such qualifier should be a neutral term, explaining concisely how clean meat products differ positively from traditional meat products, without being pejorative vis-à-vis said traditional industry. This is easier said than done and the participants so far did not reach a common view at this point. Notably, in their joint letter to the White House, Memphis Meats and the North American Meat Institute, propose use of the term “cell-based” meat or poultry to describe products that are the result of animal cell culture. The echo of this letter was heard at the Good Food Conference, as reported above.

Information requirements in the EU

Looking at the EU framework, it is questionable whether the designation “meat” can be used for clean meat products. As an argument in favor thereof, it could be mentioned such use would make it immediately apparent that these products equal traditional meat in terms of composition. Arguments countering the use of “meat” are based on the EU Hygiene Regulation. When using a grammatical approach, it should be observed that “meat” is defined as “edible parts of [a number of defined]animals” and one could wonder if cells qualify as such. When using a functional interpretation, it can be noted that hygiene requirements applicable to meat mainly relate to slaughtering, whereas clean meat obviously is not subject to slaughter. Another argument countering the use of “meat” for clean meat products is derived from the ECJ’s TofuTown case, related to veggie cheese and soy yoghurt. In legal terms, this decision answered the question whether it was permitted to use regulated product names for new product types. The answer was a clear “no”. It is anticipated that the traditional meat industry will rely on this case to counter the use of the name “meat” for clean meat product, at least without a qualifier that will prevent any misleading of the consumer. By way of background, it is helpful to remember that under EU labeling laws, it is mandatory to designate a food product by its legal name. In the absence thereof, a descriptive name can be used or alternatively, a customary name.

Summary

Clean meat and clean fish represent an emerging sector, with the promise of revolutionary innovative products. Public perception of these products, as well as trust in the safety thereof, will be of utmost importance for market success. Reliable and effective regulatory procedures as a basis for market access will therefore be pivotal. In the US, the regulatory framework applicable to clean meat products is far from clear. Firstly, it is yet to be decided which government agency has jurisdiction over these products or whether both FDA and USDA share oversight. Secondly, there are open questions regarding the appropriate regulatory pathway and in-market inspection regime. In the European Union, the regulatory pathway for clean meat products is relatively clear. Under the new EU Novel Foods Regulation, these products qualify as Novel Foods and require a market authorization from the European Commission. The Regulation as well as various EFSA guidance documents detail at length what information should be contained in a Novel Foods application. In an optimal situation, the authorization procedure could be finalized in 18 months. In both the US and the EU however, the exact designation of these products (“meat” or not?) requires further thought. On the one hand, this will require interpretation of legal product definitions and case-law and on the other hand, the interests of the traditional meat and fish sector should be taken into account.

Posted: August 16, 2018 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, novel food |

Cultured meat has been an increasingly hot topic since the first “clean meat” hamburger was introduced in London in 2013. The technology involves using cell culturing techniques to multiply a small amount of cells taken from an animal to produce foods that resemble traditional meat, poultry, and seafood. As commercial-scale production of cultured meat becomes foreseeable, regulatory agencies must determine how these products fit into their food compliance programs.”

Cultured meat has been an increasingly hot topic since the first “clean meat” hamburger was introduced in London in 2013. The technology involves using cell culturing techniques to multiply a small amount of cells taken from an animal to produce foods that resemble traditional meat, poultry, and seafood. As commercial-scale production of cultured meat becomes foreseeable, regulatory agencies must determine how these products fit into their food compliance programs.”

Harvard Law School

This is a quote taken from the website of the FDA, who organized a public meeting on 12 July 2018 to discuss safety-related data and information that the FDA is seeking on foods produced using animal cell culture techniques. Securing regulatory approval is pivotal for market access of this type of products. To date, there is no consensus how the US regulatory apparatus will classify Clean Meat products. It is neither clear which authority has jurisdiction over these products as to labeling, safety and inspections. Harvard Law School, in particular its representatives from the Food Law and Animal Law groups, is convinced of the potential benefits of Clean Meat and other cellular agriculture products. Therefore, on 9 and 10 August 2018, it organized the Clean Meat Regulatory Roundtable in order to address the regulatory concerns surrounding this new industry. A selection of topics discussed will be covered in two subsequent blogposts. The first one will cover some background information and a summary. The second one will provide an overview of the most important subjects discussed and a comparison with the EU regulatory framework where relevant.

Participants Regulatory Round Table and Ruled of Play

In order to let the discussion benefit from as many perspectives as possible, representatives from academia, the industry and from interest groups participated in Harvard’s Clean Meat Regulatory Round Table. Obviously, the meeting included a number of representatives from Harvard Law School. Furthermore, the nonprofit organizations Good Food Institute and the Animal League Defense Fund were present. The participating companies were Mosa Meat and Fork & Goode (both working on clean meat), as well as Blue Nalu (working on clean fish). From the investor side, Stray Dog Capital was represented and from the industry DuPont provided its input. Finally, a number of US lawyers were participating and I myself shared my insights from an EU perspective. All participants agreed to a Chattam House Rules + regime, meaning that the general flush of the conversation during the meeting can be reported, but the participant are not at liberty to identify, either explicitly or implicitly, what was the source of particular information.

Summary

Clean meat and clean fish represent an emerging sector, with the promise of revolutionary innovative products. Public perception of these products, as well as trust in the safety thereof, will be of utmost importance for market success. Reliable and effective regulatory procedures as a basis for market access will therefore be pivotal. In the US, the regulatory framework applicable to clean meat products is far from clear. Firstly, it is yet to be decided which government agency has jurisdiction over these products. Secondly, the regulatory pathway is still open, whereas the available procedures of do not provide an affirmative blessing from which the sector could benefit. In the European Union, the regulatory pathway for clean meat products is relatively clear. Under the new Novel Foods Regulation (effective as per 1 January 2018), these products qualify as Novel Foods and require a market authorization from the European Commission. The Regulation as well as various EFSA guidance documents detail at length what information should be contained in a Novel Foods application. In an optimal situation, the authorization procedure could be finalized in 18 months. In both the US and the EU however, the exact designation of these products (“meat” or not?) requires further thought. On the one hand, this will require interpretation of legal product definitions and case-law and on the other hand, the interests of the traditional meat and fish sector should be taken into account.

Posted: July 12, 2017 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Food, Food Supplements, Health claims, novel food | Tags: botanical, market access, medicinal, novel food |

The People’s Republic of China first law on Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicine came into force on the 1st of July 2017. This law encompasses industrial normalization by guaranteeing the quality and safety of herbs in cultivation, collection, storage and processing. Producers of Traditional Chinese Medicine (hereinafter TCM) are not only targeting the Chinese market, but are also looking for access to the European market. With this new legislation in force in China, it is a good time to have a look at the current possibilities for market access of TCM on the European market. The name “TCM” would suggest the product could only be qualified as a medicinal product. However, other product qualifications are possible as well. In this post, it will be investigated how Chinese herbal remedies and products fit into the EU framework.

The People’s Republic of China first law on Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicine came into force on the 1st of July 2017. This law encompasses industrial normalization by guaranteeing the quality and safety of herbs in cultivation, collection, storage and processing. Producers of Traditional Chinese Medicine (hereinafter TCM) are not only targeting the Chinese market, but are also looking for access to the European market. With this new legislation in force in China, it is a good time to have a look at the current possibilities for market access of TCM on the European market. The name “TCM” would suggest the product could only be qualified as a medicinal product. However, other product qualifications are possible as well. In this post, it will be investigated how Chinese herbal remedies and products fit into the EU framework.

Qualification

For market access, product qualification is vital. Qualification of TCM as medicinal products might seem obvious. However, western medicine is mostly focused on curing a certain disease or disorder, whereas TCM is focused on healing the body itself. Healing in short means the body should be strengthened to ‘treat itself’. Many of the traditional herbal remedies have healing properties, such as strengthening the immune system. As an alternative to medicinal products, other qualifications of TCM could be botanicals, so that they could be marketed as food supplements or as other foodstuffs. We previously reported on product qualification in this blog, explaining what legal tools have been developed for this purpose over time in case law. These criteria equally apply to TCM.

Simplified registration procedure for traditional herbal medicinal products

An example of a traditional herbal medicinal product we can mention sweet fennel, which is indicated for symptomatic treatment of mild, spasmodic gastro-intestinal complaints including bloating and flatulence. For this group of traditional herbal medicinal products, just like for TCM, a simplified registration regime can be found in the EU Medicinal Products Regulation. In short, the efficacy of the product containing the herb used in TCM’s can be substantiated with data on usage of the herb. This eliminates the need for costly clinical trails to prove the efficacy of the active ingredient(s) in the product. However, safety and quality of the TCM still need to be substantiated.

Eligibility for simplified registration procedure

To qualify as traditional herbal medicinal product, a number of cumulative criteria should be met, including the following.

- Evidence is available on medicinal use of the product during at least 30 years prior to application for EU market authorization, of which at least 15 years within the EU.

- Such evidence sufficiently demonstrates the product is not harmful in the specified conditions of use and the efficacy is plausible on the basis of longstanding use and experience.

- The product is intended and designed for use without the supervision of a medical practitioner and can only be administrated orally, externally and/or via inhalation.

The presence in the herbal medicinal product of vitamins or minerals for the safety of which there is well-documented evidence shall not prevent the product from being eligible for the simplified registration referred to above. At least, this is the case as the action of the vitamins or minerals is ancillary to that of the herbal active ingredients regarding the specified claimed indication(s). TCM intended and designed to be prescribed by a medical practitioner can enter the EU market, but cannot benefit from the simplified registration procedure for traditional herbal medicinal products.

Foodstuff

Currently the focus of healthcare is shifting from purely curing diseases to prevention thereof. TCM could play an interesting role in such paradigm shift. Although food business operators (hereinafter FBOs) cannot claim a foodstuff can cure a disease, such product can contribute to prevention of a disease. As such, FBOs can inform the public that consumption of a particular foodstuff can support the regular action of particular body functions. An example of a herbal remedy used in TCM and currently on the EU market is cinnamon tea; used in Chinese medicine to prevent and treat the common cold and upper-respiratory congestion. Obviously, the advantage of bringing a foodstuff (for instance, a food supplement) to the market as opposed to a medicinal product is that unless the foodstuff is a Novel Food, you do not need a prior authorization.

Novel Foods

As long as a foodstuff has a history of safe use in the EU dating back prior to 1997, FBOs do not need prior approval for market introduction. If no such history of safe use can be established, both the current and new Novel Food Regulation prescribe that the FBO receives a Novel food authorization. A helpful tool for establishing a history of safe use is the novel foods catalogue, being a non-exhaustive list of products and ingredients and their regulatory status. Another source is Tea Herbal and infusions Europe (hereinafter THIE); the European association representing the interests of manufactures and traders of tea and herbal infusions as well as extracts thereof in the EU. THIE’s Compendium, which should be read in combination with THIE’s inventory list (also non-exhaustive), contains numerous herbs and aqueous extracts thereof, which are used in the EU. Other herbs might not be considered Novel Foods, as long as the FBO can prove a history of safe use in the EU prior to 1997. For instance, the history of safe use of Goji berries has been successfully substantiated.

Traditional foodstuffs from third countries

In previous blogs we already pointed to a new procedure to receive a Novel Food authorization as of 1 January 2018, relating to ‘traditional foods from third countries’. EFSA published a guidance document for FBOs wishing to bring traditional foods to the EU market, enabling them to use data from third counties instead of European data for the substantiation of the safety of the foodstuff. The procedure is a simplified procedure to obtain a Novel Food authorization for a foodstuff, which has been consumed in a third country for at least a period of 25 years. For sure, this is not an easy one, but we have high hopes that such data can be established for TCM being used in Asia. In the affirmative, the FBO can use these data to substantiate the safety of the product and receive a Novel Foods authorization via a 4 months short track procedure, enabling the FBO to market the foodstuff at stake in the EU.

Health claims for herbal products

The EU Claims Regulation provides the legal framework for health and nutrition claims to be used on foodstuffs. In previous blogs we elaborated how such claims can be used for botanicals, being herbs and extracts thereof. So far, no authorized claims for botanicals are available, but their use is nevertheless possible under certain circumstances. In sum, an on-hold claim can be used when the FBO clearly states the conditional character thereof (by stating the number of such on hold claim on this claims spreadsheet. Upon dispute, the FBO should furthermore be able to substantiate that the compound in the final product can have the claimed effect when consumed in reasonable amounts. TCM can take advantage of this current practice, thereby communicating the healing effect thereof, which basically comes down to a contribution to general health. It should be carefully checked though, if the claim for the herbal remedy at stake has not been rejected, as happened to four claims regarding caffeine.

Conclusion

EU market introduction of TCM could take place in various ways, depending on the qualification of the product at stake. Qualification as a regular foodstuff certainly ensures the quickest way to market, as no prior market approval is required. This will be different if the product qualifies as a Novel Food. However, as of 1 January 2018, a fast track authorization procedure will be available for traditional foods from third countries, from which TCM might benefit as well. TCM could furthermore use so-called botanical claims, in order to communicate the healing effects thereof. When the TCM qualifies as a medicinal product, the good news is that for traditional herbal medicinal products, a simplified registration procedure is available under the EU Medicinal Product Directive, provided that certain criteria are met. Registration takes place via the national competent authorities in each Member State, which in the Netherlands is the Medicines Evaluation Board (CBG).

Posted: December 30, 2016 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Food, novel food |

December is the month of festivities and food. Could insects be part of this tradition in the long run? On 8 and 9 December last, the InsectCentre organized seminar on edible insects in Wageningen. The seminar brought together the insect rearing business of Europe, as well as investors and academics, to discuss opportunities and restrictions for insect rearing in Europe. The seminar covered insect autonomy, insect rearing, economics and legislation. For some background information on the opportunities of insect rearing in the Netherlands, see this document. The focus of this blog will be on the legislation regarding insects in food and feed as discussed in the seminar, combined with our sector knowledge by way of background.

December is the month of festivities and food. Could insects be part of this tradition in the long run? On 8 and 9 December last, the InsectCentre organized seminar on edible insects in Wageningen. The seminar brought together the insect rearing business of Europe, as well as investors and academics, to discuss opportunities and restrictions for insect rearing in Europe. The seminar covered insect autonomy, insect rearing, economics and legislation. For some background information on the opportunities of insect rearing in the Netherlands, see this document. The focus of this blog will be on the legislation regarding insects in food and feed as discussed in the seminar, combined with our sector knowledge by way of background.

Why the interest in insects?

Insects are extremely versatile and can be put to use in many ways. Insects are the most species rich class of organisms on earth, of which (approximately) 2.500 species are edible. In EFSA’s 2015 report on ‘Risk profile related to production and consumption of insects as food and feed’, 12 of the 2500 edible species are mentioned as having the biggest potential to be used in food and feed. In other parts of the world, insects are a staple food and some insects are even seen as a delicacy. The two most commonly commercially reared insects in the EU for feed applications are the larvae of the black soldier fly and for food applications the lesser mealworm (buffalo) seems to have the best potential. Many insects are pathogenic or too small in size to be commercially interesting to rear. However, during the past years, steady growth in the worldwide demand for alternative protein sources has lead to a renewed interest in insects as a potential source of food and feed. Insects can be viewed as mini short cycled livestock for producing protein. Insect protein is an interesting source of protein due to the quality of the insect protein as opposed to plant-derived protein. Animal protein (so also insect derived protein) has a superior amino acid content compared to plant-derived protein. With a growing world population, the demand for meat production and protein will only increase. Currently soya is imported into the EU for feed purposes. Insects might be a (partial) replacement for this soya in the future, and can even be produced in the EU instead of being imported.

Insects in food

Insects can be reared to produce food as a whole or processed as ingredients for food. As explained in one of our previous blogs, only in some Member States a number of insects are permitted to be used in food, meaning that no enforcement measures regarding such use is taking place. The previously mentioned EFSA report contains the assessment of the risks associated with insects used in food and feed. In short, the overall conclusion was that the safety of farmed insects for use in food and feed strongly depends on both the substrate and the processing of the insects. Further research is needed to be able to fully assess the safety of insects to be used in food and feed.

Current and future regulatory status of insects

Under the current Novel Food Regulation, whole insects are not explicitly regarded as Novel Foods. The rationale therefore is that the category of “food ingredients isolated from animals” are not considered to cover animals (insects) as a whole. However, this will change under the new Novel Food Regulation, entering into force on 1 January 2018, as of when insects will be considered Novel Foods. See our previous blog for further info on the contents of this regulation and the changes in respect of the current Regulation. Under the new Novel Foods regime, it remains to be seen how the competent authorities of the Member States will deal with FBO’s currently using insects in food.

Enforcement as of 1 January 2018

Even if EFSA concluded that additional information is required to assess the safety of insects in food in full, considerable experience has been gained already with the application of insects in food. As far as we are aware, no safety issues have been reported regarding these applications. As safety is the bottom line for enforcement, we take the view that enforcement measures without any safety incidents are not justified just like that. This in particularly applies with respect to products containing only a small percentage of insect derived protein. On the other hand we know that insect manufacturers are using the transition period until 1 January 2018 to compile a full Novel Food dossier based on the Guidelines that were made available in September this year. Taking into account that the new Novel Foods Regulation also contains a regime for data protection, they justify the investment involved to secure a competitive edge the field of alternative protein.

Insects in feed

Two restrictions currently hinder the growth of the insect sector for feed production. The first is a prohibition of certain types of animal protein in feed, commonly referred to as the ‘feed ban’, and secondly, the restrictions on certain types of feed for the insects.

Feed ban

The feed ban, was introduced as a reaction to the BSE crisis, and is laid down in the TSE Regulation. This ban prohibits the use of animal derived protein to be used in feed for farmed animals, unless an explicit exception is made. Insects could have a great potential in feeding farmed animals such as poultry and pigs and also for use in aquaculture. Currently the possibilities for feeding insects to farmed animals and aquaculture animals are limited. However, the European Commission published a draft amendment to the TSE Regulation to partially uplift the feed ban. The amendment will enable the use of certain insects for the production of Processed Animal Protein (PAP) for the use in aquaculture. Discussions whether the use of PAP could be extended to poultry and pig farming are currently on going.

Food to feed the insects

In addition to the prohibition on the use of insect protein in feed, the materials that can be lawfully used to feed the insects are limited. From a circular economy point of view, the use of manure to rear insects could be attractive. In this way manure could be used to produce feed and the insects could transform the nitrate contained in the manure, that would otherwise contaminate the environment, into valuable nutrients for poultry. However, when rearing insects to produce feed, the insects are considered to be farmed animals (similar to cows or poultry). The Animal By-products Regulation prohibits the use of certain materials in feed for farmed animals, manure being one of them. The ideal situation for the insect rearing industry would be to be able to use all types of other waste stream for rearing insects. This is not possible. Currently only waste streams fit for human consumption and some waste streams of animal origin, such as milk and milk derived products, can be used as feed for insects.

Conclusion:

During the Wageningen seminar referred to in the introduction, the overall opinion of both the presenters and participants was that European legislation currently restricts commercial use of insects for both food and feed applications. On the one hand, the new Novel Foods Regulation will bring legal certainty on the Novel Food status of insects, on the other hand it will require FBO’s marketing insect based food products to obtain a Novel Food authorization. However, for feed there is light at the end of the tunnel. We conceive the exception for PAP of certain insects to be fed to aquaculture to be a first step in getting insects on the menu for poultry and other farmed animals as well. As always, we will keep you posted on developments regarding the use of insects in both food and feed.

The author has written this post together with her colleague Floris Kets, who attended the seminar organized by the Insects Centre.

Posted: October 28, 2015 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Enforcement, Food, novel food |

The heat was on today in the European Parliament (EP). The reason for that was that the new Novel Foods Regulation was put to vote in a plenary session. In the debate prior to the vote, the opinions centred between concerns about food safety and the free circulation of goods. In this post, you will be updated about the outcome of the vote. In short, the adoption of the new Novel Foods Regulation will have important consequences for Food Business Operators (FBO’s). In an earlier post, we already reported about streamlined authorisation procedures. Today, we will mainly focus on the type of products covered by this legislation. Insects are in for a start. In a 10 minutes read, you will learn what are the consequences thereof – and more.

The heat was on today in the European Parliament (EP). The reason for that was that the new Novel Foods Regulation was put to vote in a plenary session. In the debate prior to the vote, the opinions centred between concerns about food safety and the free circulation of goods. In this post, you will be updated about the outcome of the vote. In short, the adoption of the new Novel Foods Regulation will have important consequences for Food Business Operators (FBO’s). In an earlier post, we already reported about streamlined authorisation procedures. Today, we will mainly focus on the type of products covered by this legislation. Insects are in for a start. In a 10 minutes read, you will learn what are the consequences thereof – and more.

Shaping the new Novel Foods Regulation

Today (28 October 2015), the EP adopted the latest proposal for a Regulation on Novel Foods [insert final text]. As reported in one of our previous posts, the European Commission published an initial proposal for this Regulation in December 2013. EP Rapporteur Nicholson heavily criticised this draft, mainly for its open product definition and for the lack of streamlining the authorisation procedure. As a result, an EP legislative proposal became available, in which the Rapporteur formulated a number of improvements. Most of them were included into the draft legislation approved by the ENVI committee by the end of November 2014, which further developed into the text voted today. This adopted proposal will enter info force after publication in the OJ. However, a transition period of 24 months after such publication has been provided before its actual application.

So what are Novel Foods finally?

In the initial Commission proposal, the various product categories had not been exhaustively defined. Although such a system could present the advantage of flexibility, in fact FBO’s resisted against the legal uncertainty this would create. As a result, the approved draft by the ENVI Committee identified 10 categories of Novel Foods. Some of these have again been heavily debated, like for instance insects – however without success. The Regulation voted today in the EP defines the following products as Novel Foods:

- food with a new or intentionally modified molecular structure;

- food consisting of or isolated / produced from microorganisms, fungi or algae;

- food consisting of or isolated / produced from material of mineral origin;

- food consisting of or isolated / produced from plants or their parts, except when the food has a history of safe food use in the Union and one out of two alternative conditions are met;

- foods consisting of or isolated / produced from animals or their parts, except where these animals were obtained from traditional breeding practises and the food from those animals has a history of safe food use;

- food consisting of or isolated / produced from cell or tissue culture derived from animals, plants, micro-organisms, fungi or algae;

- food resulting from a production process not used within the Union before 15 May 1997, giving rise to significant changes in the composition or structure of a food, affecting its nutritional value, metabolism or level of undesired substances;

- food consisting of engineered nanomaterials;

- vitamins, minerals and other substances, where a new production process has been applied or where they contain engineered nanomaterials;

- food used exclusively in food supplements within the Union before 15 May 1997, where it is intended for use other than in food supplements.

What’s in? – Most striking changes

Contrary to the ENVI proposal, the current text of the Regulation no longer mentions food derived from cloned animals or their descendants as a separate product category. However, it becomes clear from the recitals in the new Novel Foods Regulation that no change is intended here. Until specific legislation on food from animal clones enters into force, such food is covered by category nr. 5 of this Regulation, as food from animals obtained by non-traditional breeding practises. Another textual change relates to category nr. 8. Whereas the ENVI draft still specified the highly debated 10 % threshold for a food ingredient to qualify as nano (instead of the 50 % threshold proposed by the Commission), no such threshold is contained in the current text. Although this is no doubt a compromise solution, it is expected it shall give rise to new discussions. A real change with respect to the ENVI proposal relates to product category nr. 3, covering food of mineral origin. For now, the background of this change remains unclear. Finally, insects are still covered by category nr. 4. Today, many food products consisting of or containing insects are marketed in various Member States. It is therefore important to establish what will be the consequences of considering insects as Novel Foods. In order to answer that question, the provisions laying down the transition regime are of interest. Furthermore, by way of background, a number of safety evaluations of insects as food are briefly discussed.

Evaluation of insects as food by certain Member States

In one of our previous blogs relating to the marketing of insects as food products, we reported that due to the lack of clarity regarding the status of insects (Novel Foods or not?), some Member States issued their own guidance. In Belgium for instance, the placing on the market of 10 particular insects species as food product is tolerated, provided that specific food law requirements are met. In the Netherlands, the Dutch Food Safety Authority and the Health Minister ordered a safety report with respect to three types of insects currently marketed as food in the Netherlands. These are the mealworm beetle, the lesser mealworm beetle and the locust, regarding which the heat-treated and non-heat treated consumption was evaluated in terms of chemical, microbiological and parasitological risks. Based on the outcome, it was recommended to consider these insects as “regular” foods (in the sense of the General Food Law Regulation) and not as Novel Foods.

Evaluation of insects as food and feed by EFSA

On 8 October 2015, EFSA published its Risk profile related to production and consumption of insects as food and feed ordered by the Commission. In fact, EFSA was requested to assess the micro-biological, chemical and environmental risks posed by the use of insects in food relative to the risks posed by the use of other protein sources in food. EFSA found that for the evaluation of micro-biological and chemical risks, the production method, the substrate used, the stage of harvest, the specific insect species and the method of further processing are of relevance. It established however that with respect to any of these topics, fairly limited data are available. It therefore strongly recommends further research for better assessment of microbiological and chemical risks from insects as food, including studies on the occurrence of hazards when using particular substrates, like food waste and manure.

Transition regime

How to deal with insects as food products that are currently marketed? The new Novel Food Regulation provides first of all that these products do not have to be withdrawn from the market. However, for the continued marketing of such food products a request for authorisation should be filed within 24 months after the date of application of the new Novel Food Regulation. This would come down to the following.

- Entry into force of new Novel Foods Regulation: 1 January 2016 (assumption)

- Date of application of new Novel Foods Regulation: 1 January 2018

- Ultimate date for filing authorisation for continued marketing of insects as food: 1 January 2020.

This means that roughly speaking 4 years from now, FBO’s offering insects as food should still obtain a Novel Food authorisation. Assuming that these products have been marketed since the end of 2014 (see for instance the news on the launch of the insect burger sold by Dutch grocery chain JUMBO), this would mean that they were on the market 5 years before. If no safety concern ever arose so far, it would not be unreasonable to request an exemption from this obligation. At any rate, such FBO’s should know that prior to the indicated date of 1 January 2020, they can most likely successfully rebut any enforcement measures by local food safety authorities.

Conclusion

The adoption of the new Novel Foods Regulation has been a process with quite a few hick-ups and some surprising results. Whereas food from cloned animals for a long time had been the cause of delay, it is surprising to see that this Novel Food category nevertheless ended up within the scope of the new Novel Foods Regulation. As to products providing alternative protein, such as insects, we understand that the safety aspects from rearing to consumption should be carefully assessed. However, we note that EFSA does not have any immediate safety concerns per se. Furthermore, it should be stressed that the notion of “safety” in EU food law has only been negatively defined. That is, food is safe as long as it is was not found unsafe. Therefore, we consider that alternative protein products that were marketed for a number of years without any problems reported should not be subject to further barriers. Anyhow, FBO’s should be aware of their rights of continued marketing of such products, at least for four more years to come.

Want to know more about this subject? Do join the Axon Seminar on Alternative Proteins: invitation seminar.

Image: Amsterdam Westerpark, food festival “The Rolling Kitchens“, serving snacks made out of insects, such as fried grasshoppers on a stick or mealworm spring rolls.

Posted: May 15, 2015 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Food, Information, novel food |

On 5 and 6 May 2015, the Vitafoods Europe Conference took place in Geneva. For companies active in the ingredient business, this is the yearly meet up to share the latest ingredients insights, to present new products and to prepare actual or future deals. Axon Lawyers was asked to participate in the Conference Program, which this year was committed to three different steams, being “your business”, “your science” and “your product” respectively. Axon Lawyers presented two topics in the business stream, pertaining to EFSA Claims and Regulatory Issues and to Labelling. Below, some background with respect to these presentations will be provided and the actual presentations will be shared.

On 5 and 6 May 2015, the Vitafoods Europe Conference took place in Geneva. For companies active in the ingredient business, this is the yearly meet up to share the latest ingredients insights, to present new products and to prepare actual or future deals. Axon Lawyers was asked to participate in the Conference Program, which this year was committed to three different steams, being “your business”, “your science” and “your product” respectively. Axon Lawyers presented two topics in the business stream, pertaining to EFSA Claims and Regulatory Issues and to Labelling. Below, some background with respect to these presentations will be provided and the actual presentations will be shared.

WRAP-UP OF NOVEL FOODS PRESENTATION

Rationale of Novel Food legislation for ingredient innovations

Karin Verzijden presented a topic on the status quo of Novel Foods (NF) in the EU under the new Regulation, in which she focused on the rationale of NF legislation for ingredient innovations. As reported earlier, a new NF Regulation was presented by the Commission in December 2013, which was heavily amended based on the input from EP Rapporteur Nicholson. In November 2014, the ENVI Committee accepted draft legislation including most of the Nicholson amendments. This text represents the current status quo of NF legislation and now awaits first reading in the European Parliament (EP). The EP approved text will constitute the final legal framework.

Alternative proteins

Developments in alternative proteins, meaning proteins derived from other than animal sources, was a key trend at Vitafoods, reported FoodIngredientsFirst. Amongst those sources for alternative proteins are algae, insects and duckweed inter alia. In the presentation made at Vitafoods, the importance to know the regulatory status of each of these sources of ingredients was explained (“Begin with the end in mind“). Ingredients that have been marketed as a source of food in the EU prior to 1997 to a significant extent are clearly outside the scope of the Novel Foods Regulation. As a consequence, they are not subject to pre-market authorization, at least not based on the NF requirements. If to the contrary, no valid case for a history of safe use can be made, then it is likely that a NF authorization will have to be obtained.

Regulatory status of algae

Such history of safe use was already established for various algae, like for instance specific types of the Chlorella and Laminaria algae. As a consequence, these ingredients can be used for food products without being subject to NF authorization, both under the current and future legal regime. The same does not apply to for instance the Rhodymenia palmata, regarding which so far only evidence on use as a food supplement is present. Such use can be of support to demonstrate the safety thereof, but as a single source will not be enough to market the product as a NF. For that purpose, it is likely that a NF authorization will have to be obtained.

Regulatory status of insects

Insects are well-known to be a rich source of proteins. Under the current NF legal framework, they are not considered to be Novel Foods, at least not explicitly so. This is likely to change under the new NF Regulation, as one of the new NF product categories reads “Food consisting of, isolated / produced from animals or their parts, including whole animals like insects, except where a history of safe use within the Union can be established”. As pointed out in one of our previous blogposts, this is contrary to the practice in some Members States, where the safety of various insects as a food ingredient has been established. Also, in practice, various insect based products are effectively marketed – examples can be found here and here. It will therefore be interesting to see if those products will be subject to enforcement measures of national health authorities. We believe that the longer those products have been marketed the more difficult this will be based on, amongst others, the principle of legal certainty.

Regulatory status of duckweed

Duckweed is reported to contain, depending on its cultivation procedure, 40 % proteins, whereas it grows much quicker than algae. Therefore this aquatic biomass could be an interesting source of alternative proteins too. Under the current legal framework, it would certainly be an option to investigate if any substantial equivalence to existing foods could be established. As a starting point, the protein RuBisCo, that occurs both in duckweed and in many green plants could be taken. If this is of no avail, it is interesting to know that under the future legal framework, the short cut authorization based on traditional foods from third countries might be available. Such will depend on the outcome of research into duckweed as a source of food in those countries, regarding which in such case a history of safe use for 25 years will have to be demonstrated.

WRAP-UP LABELLING PRESENTATION

Designing clearer labels for consumers

Since the entry into force of the Food Information to Consumers Regulation (“FIC Regulation”) on 13 December 2014, some experience has been gained with the new labelling rules applicable to all food products sold to end consumers. Sofie van der Meulen presented a topic on labelling, explaining the new requirements and how these are applied in practice.

Scope

The FIC Regulation aims to modernize, simplify and clarify the food-labelling scene by recasting the horizontal labelling provisions and merging them into one single Regulation. However, labelling is still not fully harmonised due to language requirements and room for national measures, for example on allergens and additional mandatory information to be stated on the label.

The provisions of the FIC Regulation are supposed to enable consumers to choose a healthy diet and they apply to food business operators (“FBO’s”) in all stages of the food chain who supply food to the final consumer. The FBO under whose name the food is marketed or the importer into the Union market is responsible for compliance. Since a lot of products are sold via the internet nowadays, the FIC Regulation explicitly applies to online sales of food products as well. Consumers’ have to receive particular information in a webshop prior to the purchase of the food product.

Food information

In general, food information shall not be misleading, must be accurate and shall not attribute pharmaceutical characteristics to food. The latter because the food would then be covered by the medicinal products Directive.

Article 9 of the FIC Regulation lists the mandatory particulars to be stated on all labels. Where should the information be stated? With regards to prepacked food, the information should be stated directly on the product or on a label attached thereto. The information should be easily visible and clearly legible. That’s is why detailed legibility requirements are laid down in the FIC Regulation. The minimum font size of the characters should be 1.2 mm or 0.9 mm if the packaging is smaller than 80 cm2. The language used on the label should be a language that is easy understandable in the Member State where the food product is marketed. In practice most FBO’s decide to use the official language of the Member State on their labels, or, as a very minimum, on their website.

Allergens

Declaring the presence of any of the 14 listed allergenic ingredients has been a requirement since 2003. However, under the FIC Regulation the way they should be declared has changed. For prepacked foods allergens must be listed in the list of ingredients with a clear reference to the name of the allergen as listed in Annex II of the Regulation. Furthermore, the presence must be emphasized by using a different typeset that distinguishes them from the rest of the ingredients. This can be achieved by using a different font, style or background colour. The provision of allergen information for non-prepacked foods sold in, inter alia, cafes, canteens and restaurants are subject to national requirements. In the Netherlands this information can be provided orally, but for example in Ireland this information has to be provided in a written format.

Country of Origin Labelling

As of 1 April 2015 Country of Origin Labelling (‘COOL’) has been extended from beef to other unprocessed meats widely consumed in the EU. See this previous blogpost for more information on this particular extension. In the future, mandatory COOL could be further extended under the FIC Regulation and become applicable to other products such as milk and milk products and also to processed meats.

Nutrition declaration and the use of health and nutrition claims

Under the FIC Regulation, a nutrition declaration will become mandatory for most food products as from 13 December 2016. However, if health and nutrition claims are used, including a nutrition declaration on the label is already mandatory.

The nutrition declaration should state the energy value in calories and the amounts of fat, saturates, carbohydrates, sugars, protein and salt. This information should, as a main rule, be expressed per 100 g or 100 ml in order to enable the consumer to compare products and make a choice for a healthy diet. Exceptions apply to food supplements and mineral waters.

Consequences of non-compliance

Non-compliance could give rise to administrative sanctions such as administrative fines. Intended mislabelling could qualify as forgery under criminal law and be prosecuted. A Dutch meat trader was recently sentenced to 2.5 years in prison, as he was found guilty of forgery when horsemeat was not declared on the label of beef products. The Dutch Food Safety Authority currently focuses on misleading information on prepacked foods in 2015.

Conclusion

Both the topic of Novel Foods and Labelling is expected to evolve over time. For Novel Foods this is the case, since the legal framework has not yet been finalized. For labelling, this also applies, as the Commission still has to provide input on specific topics and also at national level, there is some room for manoeuvre. At Food Health Legal, we continue to follow and report these developments. Stay posted and do send us your comments!

Posted: January 9, 2015 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Food, novel food |

Further developments in Brussels took place since we last reported on the new Novel Foods Regulation. Draft legislation was approved in this respect by the ENVI Committee, awaiting the first reading of the European Parliament (EP). The current status quo was published in a Report dated 26 November 2014. Two particular subjects seized most public attention, notably the moratorium proposed on the use of nanomaterials in food and the compulsory labelling of cloned food products. These two items have been covered here and here inter alia and will be shortly touched upon below. Most of all however, this post will focus on the adjusted Novel Food definition. We consider this subject to be of the essence, whereas so far was not highlighted at all.

Further developments in Brussels took place since we last reported on the new Novel Foods Regulation. Draft legislation was approved in this respect by the ENVI Committee, awaiting the first reading of the European Parliament (EP). The current status quo was published in a Report dated 26 November 2014. Two particular subjects seized most public attention, notably the moratorium proposed on the use of nanomaterials in food and the compulsory labelling of cloned food products. These two items have been covered here and here inter alia and will be shortly touched upon below. Most of all however, this post will focus on the adjusted Novel Food definition. We consider this subject to be of the essence, whereas so far was not highlighted at all.

Moratorium nanomaterials and change to nano definition

The legislation takes as a starting point that food production processes involving nanotechnologies require specific risk assessment methods. These methods should have been assessed by EFSA prior to use. Furthermore, an adequate safety assessment on the basis of those methods should have shown that the foods at stake are safe for human consumption. The rationale of all this is the precautionary principle: emerging technologies in food production may have an impact on food safety. On top of that, the definition of nanomaterials was changed, introducing a 10 % nano-particles threshold for a food ingredient to qualify as “nano” instead of a 50 % threshold. This was in line with EFSA recommendations, but it may pose a serious problem to FBO’s currently marketing nano-foods. Using the 10 % threshold would imply that quite a few product currently marketed would, under the new Novel Foods Regulation, qualify as Novel Food whereas it currently does not. This will not benefit to legal certainty.

Compulsory labelling of cloned food products

During the long term discussions on the renewal of the Novel Food Regulation, it was decided that the subject of food from cloned animals would be left out. As a result, the Commission published two separate Directives on food from animal clones and on cloning on certain animal species for farming purposes respectively (the draft “Cloning Directives”) in December 2013. These two proposals have now been turned down by EP, as they did not address the food obtained from clones’s offspring. Until food from cloned animals will be covered by revamped Cloning Directives, cloned meat products have been brought within the scope of the Novel Food Regulation and they should be labeled as such.

Adjusted Novel Foods definition

Contrary to current legislation, the initial draft Novel Food Regulation contained an open product definition, where the listed categories of products merely served as examples. This was heavily criticised by rapporteur James Nicholson. Based on his consultations in the field, such open product definition according to him constituted a source of legal uncertainty. Instead, he suggested re-introducing the former product categories in an updated form in order to make this Resolution future-proof. In fact, this suggestion was followed, but somehow pushed to the extreme. The draft Novel Food definition currently also covers product categories that were never considered as Novel Foods before, such as insects and food obtained from cellular or tissue cultures.

10 categories of Novel Foods

The definition currently proposed for a Novel Food is a food that was not used for human consumption to a significant degree in the Union before 15 May 1997 and that falls under at least one of the ten following categories:

- Food with a new or intentionally modified primary molecular structure;

- Food consisting of, isolated / produced from microorganisms, fungi or algae;

- Food consisting of, isolated / produced from plants, except for plants having a history of safe food use within the Union;

- Food derived from cloned animals and / or their descendants;

- Food containing, consisting of, or obtained from cellular or tissue cultures;

- Food consisting of, isolated / produced from animals or their parts, including whole animals like insects, except where a history of safe use within the Union can be established;

- Food resulting from a new production process not used for food within the Union before 15 May 1997 affecting its nutritional value inter alia;

- Food containing nanoparticles;

- Vitamins and minerals (i) subject to the new production process referred to under (7) or (ii) containing nanoparticles referred to under (8) or (iii) for which a new source of starting material has been used;

- Food used exclusively in food supplements within the Union before 15 May 1997, where it is intended for use in other foods than food supplements.

What’s new actually?

Some of the categories mentioned above were already included in the 1997 Regulation, being those mentioned above under (1), (2), (3) and (7). Others were introduced in the initial Commission proposal for a new Novel Foods Regulation, notably those mentioned above under (8), (9) and (10). Truly new are therefore only the categories consisting of food derived from cloned animals (4), food obtained from cellular or tissue cultures (5) and food produced from whole animals such as insects and from animal parts (6). As explained above, the category consisting of food obtained from cloned animals is likely to be temporary. As soon as specific legislation covering this topic will be in place, such legislation will be applicable to cloned food products instead of the Novel Foods legislation. What are the consequences of the introduction the two other new categories? This will be discussed below.

Food obtained from cellular or tissue cultures are Novel Foods

As a good example of foods obtained from cellular cultures, the in-vitro burger engineered by Prof. Mark Post from the University of Maastricht (see picture from neontommy.com) can be mentioned. This burger was constructed on the basis of a tiny part of meat, using stem cell technology. For this purpose muscle cells harvested from a living cow were fed and nurtured, so that the single strand of cells multiplied to produce numerous new strands. In the end, 20.000 of those strands were assembled and put together in a hamburger. Obviously, the cell production used for this purpose will have to be increased for this technology to become a viable meat production method. However, now that the feasibility of this method in essence has been demonstrated, its application is not inconceivable. When in future, lab-burgers like the one from Maastricht will be marketed as food products, they will need to obtain pre-market authorization based on the current draft for the new Novel Food Regulation. This is understandable, as the use of this technique and starting material for food production is completely new and their safety needs to be established.

Food produced from insects are also Novel Foods

For numerous companies this may come as some surprise. Contrary to the use of cellular tissue for the production of food, the use of insects as food goes back to biblical times. Actually, in various European countries including the Netherlands and Belgium, insects are being offered for sale as food. For instance, Dutch supermarket chain JUMBO offers edible insects for sale as of October 2014. This has incentivised national authorities to investigate the safety of consumption of insects and to formulate basic requirements for rearing facilities. As a result, recommendations were made in the Netherlands that a specific number of insects, such as the mealworm beetle and the locust, should be considered as foods under the General Food Law Regulation (see our previous blogpost for more detailed information also covering other European countries). It should be observed that not all European countries are at the same page here. In Luxemburg for example, the marketing of edible insects, pending an EFSA opinion awaited for July this year, is prohibited.

Discussion

We welcome that the open product definition for Novel Foods has been abandoned, as this increases legal certainty. It is questionable though to what extent it was wise to re-integrate food derived from cloned animals and / or their descendants into the Novel Food Regulation. During previous revision efforts of this Regulation, this topic was exactly the bottleneck why the revision could not be completed. Also, this does not serve as an incentive for the Commission to adjust its previous proposals for the Cloning Directives at short notice. We are more positive with respect to the introduction of the new category of Novel Foods relating to food produced from cellular cultures. This is exactly the type of high tech sustainable food, which in essence is a Novel Food. The same does not apply however with respect to insects. It is striking that up to and including the first Report by Rapporteur James Nicholson, whole animals such as insects never formed part of the Novel Food product definition. We are under the impression that they now landed therein by way of surprise. This is not consistent with current practise of various Member States and will pose a problem for many FBO’s actually marketing food produced from insects. Furthermore, there seems to be a substantial amount of evidence for safe consumption of insects, at least in the Netherlands. Therefore, instead of qualifying whole animals as insects instantly as Novel Foods, as an alternative for providing international industry standards, it could be considered to include a list of recommended edible insects into the Codex Alimentarius.

Conclusion

It is expected that the current draft legislation for the new Novel Foods Regulation will not be the final text. We expect active lobbies from FBO’s marketing nano-foods to oppose the adjusted definiton for nanomaterials. Likewise we expect, and we recommend, that FBO’s marketing insects or food from insects will oppose the fact that food made from whole animals like insects qualify as Novel Foods per se. The chances of success will depend, inter alia, on the expected EFSA report on certain risks of the production and consumption of insects. As of now however, there is already safety evidence which could be relied on pending the final text of the Novel Foods Regulation.

Posted: November 27, 2014 | Author: Sofie van der Meulen | Filed under: Food, novel food |

Do bugs have a place on your dinner plate other than the fly that lands on it or the caterpillar that accidently ended up in your dish, as it happened to live in the cauliflower you prepared for dinner? If you live in Europe you are likely to answer this question with ‘no’ and you might even have a slightly disgusted look on your face right now…

Do bugs have a place on your dinner plate other than the fly that lands on it or the caterpillar that accidently ended up in your dish, as it happened to live in the cauliflower you prepared for dinner? If you live in Europe you are likely to answer this question with ‘no’ and you might even have a slightly disgusted look on your face right now…

FAO and European Commission on insects

In other parts of the world certain insects are part of people’s diet and are sometimes even considered as a delicate and exclusive bite. The call to expand the consumption of edible insects worldwide recently became louder. According to the UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), insects can potentially help solving the increasing demand for animal protein. In 2013 FAO published the report ‘Edible insects’ and in May 2014 the first international conference ‘Insects for food and feed‘ was organized in the Netherlands in collaboration between Wageningen University and FAO. This video provides a summary of the conference. Furthermore, Wageningen University announced the launch of the first scientific journal focussing on this topic in 2015. On 27 November 2013 the Director General for Health and Consumers mentioned edible insects as an interesting alternative source of protein in her speech:

‘Looking to the future, feeding a growing world population will inevitably increase pressure on already limited resources – land, oceans, water and energy. The development of alternative sources of protein will no doubt grow in importance and significance to meet the future protein demand. Such sources include cultured meat, seaweed, beans, fungi and, of course, insects. The greater use of insects is an interesting alternative both for human consumption and animal feed, given the prospect of high protein yields with low environmental impacts.’

Are edible insects Novel Foods?

During the abovementioned conference it became clear that there was an urgent need to develop legislation on edible insects to give the food and feed industry clear guidance on the requirements they have to meet. This discussion paper provides a look at the regulatory frameworks influencing insects as food and feed at international, regional and national levels. This paper, however, is not exhaustive. The European Commission has asked EFSA to deliver a scientific opinion on the risks of insect consumption, but this opinion is expected in 2015 at the earliest. Another question is whether insects should be considered Novel Foods covered by EC Regulation 258/97. According to this Regulation, Novel Foods require pre-market approval in the EU (Do you want to read more about Novel Foods? Check this, this and this post). At this moment the European Commission has not explicitly decided on whether insects should be considered Novel Foods or not. Until a clear position and a harmonization of the novel food status of insects at European level have been adopted, some Member States decide to apply their own ‘rules’ for the placing on the market of insects intended for human consumption.

Belgium

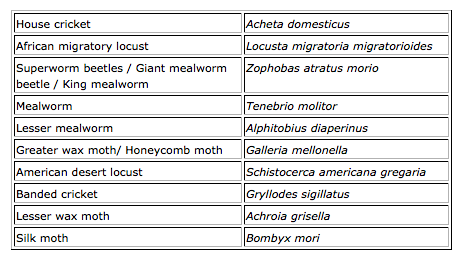

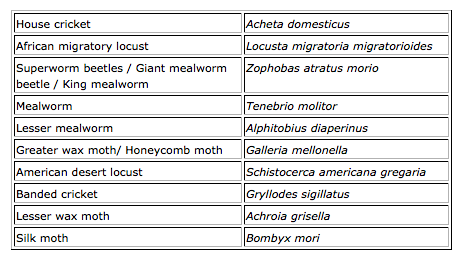

In Belgium the placing on the market of the species included in the table below is tolerated, provided that the requirements of food legislation are met, especially and among others the application of good hygiene practices, traceability, compulsory notification, labelling and organisation of a self-checking system based on the HACCP principles. This tolerance does not apply to food ingredients isolated from insects, such as protein isolates.

Also France and the United Kingdom seem to tolerate the sale of edible insects in their countries. If you have any additional information from your country or region to include in this post, you are cordially invited to share this with us through info@axonlawyers.com.

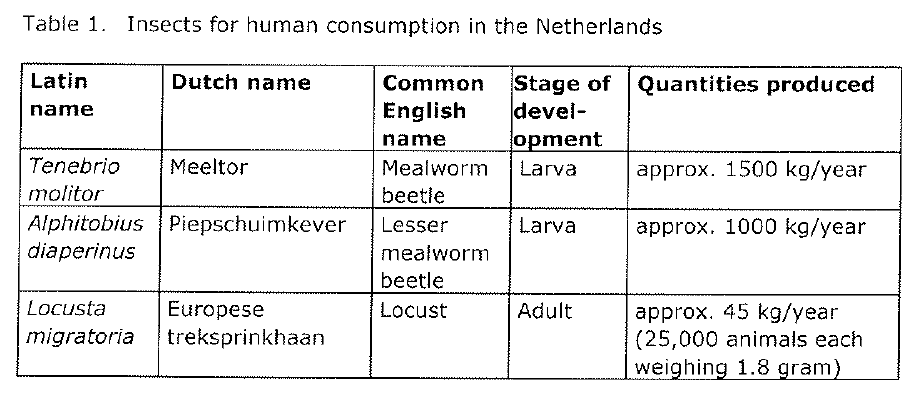

The Netherlands

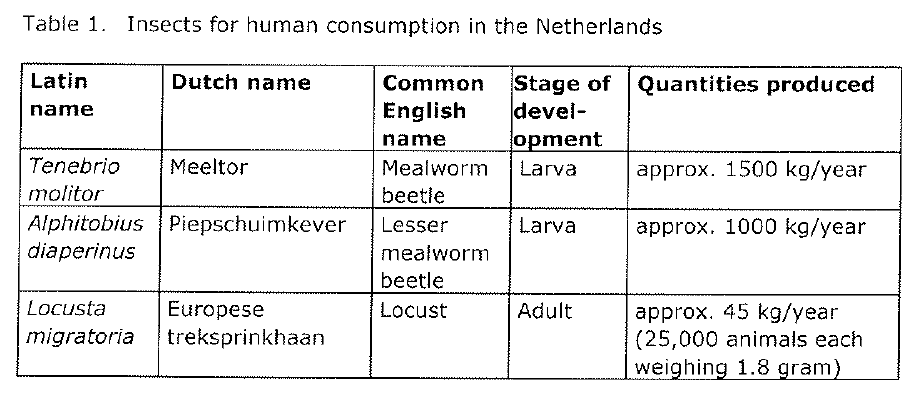

On 15 October 2014 the Dutch Office for Risk Assessment & Research (in Dutch ‘Bureau Risicobeoordeling & onderzoeksprogrammering‘, herinafter: ‘BuRO’) published their advisory report to the Inspector-General of the Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (in Dutch: ‘NVWA’) and the Dutch Ministers of Health Welfare and Sport and Agriculture. According to this report the following insects are currently produced and sold in the Netherlands.

The NVWA asked to assess the chemical, microbiological and parasitological risks of consuming heat-treated and non-heat-treated insects. The risk assessment was limited to the three species mentioned in table 1 above. BuRO recommends the Ministers to treat those insects as foods in the meaning of the General Food Law (Regulation 178/2002) that are required to comply with the hygiene regulations (Regulations 852/2004 and 853/2004) and all other food-related legislation. Those insects are not treated as Novel Foods in the Netherlands.

With regards to food safety, BuRO recommends the NVWA to use the following minimum requirements for rearing facilities:

- Products introduced to the market must have been heated to reduce microbiological risks. The hygiene criteria for processing of raw materials in meat preparations should be used.

- Food safety criteria for insect products: