Posted: October 23, 2023 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Food, New Genomic Techniques, organic |

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) do not generally receive a warm welcome from the average EU citizen. Possibly this is a case of ‘unknown makes unloved’. But GMOs can also bring positive things, for example, in the field of plant breeding. This summer, the European Commission published a proposal for an NGT Regulation. What exactly does this proposal entail and what are the expected consequences in practice? And how was this proposal received by the European Parliament in its draft report of 16 October last in the first reading of the legislative procedure?

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) do not generally receive a warm welcome from the average EU citizen. Possibly this is a case of ‘unknown makes unloved’. But GMOs can also bring positive things, for example, in the field of plant breeding. This summer, the European Commission published a proposal for an NGT Regulation. What exactly does this proposal entail and what are the expected consequences in practice? And how was this proposal received by the European Parliament in its draft report of 16 October last in the first reading of the legislative procedure?

Potential benefits GMOs and reluctance

GMOs can help develop plants that are more drought tolerant or less susceptible to certain fungi. This reduces the need for pesticides in cultivation, precisely one of the objectives of the EU Farm-to-Fork strategy that the Commission published at the beginning of its mandate in May 2020. At the same time, in the Netherlands the proposal for the NGT Regulation prompted Odin, Demeter, Ekoplaza and Greenpeace, among others, to start a petition calling for “Keep our food genetically modified free.” (in Dutch: Houd ons voedsel gentech vrij). At the time of writing this blogpost, the petition counts 47.709 signatories.

Scope of application NGT Regulation

The intended Regulation applies to NGT plants and to NGT products, meaning food and feed containing or consisting of or produced from NGT plants and other products containing or consisting of such plants. NGT plants are obtained from the following two genomic techniques or a combination thereof:

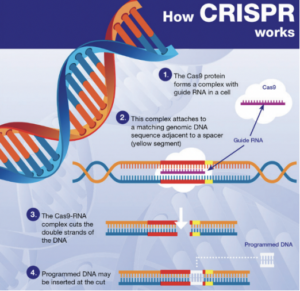

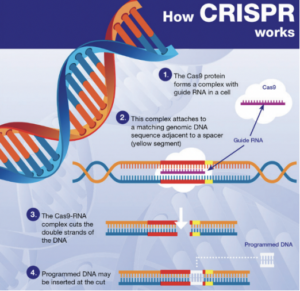

- Targeted mutagenesis: this is a technique that results in changes to the DNA sequence at precise locations in an organism’s genome;

- Cisgenesis: this is a technique that results in the insertion, into the genome of an organism, of genetic material already present in the total genetic information of that organism or another taxonomic species with which it can be crossed.

In essence, NGTs are genomic techniques such as CRISPR-Cas9. These techniques result in more targeted genomic modifications than older genomic techniques, which often involve the introduction of heterologous genetic material. The European Commission therefore recognizes that any risks associated with the use of NGTs are lower than those associated with older genetic techniques. This is what the risk assessment in the draft Regulation specifically addresses.

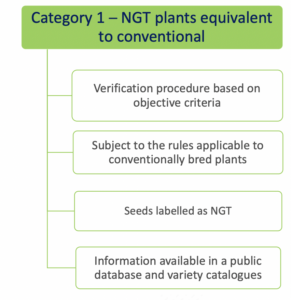

Two specific regulatory regimes for category 1 and category 2 NGT plants

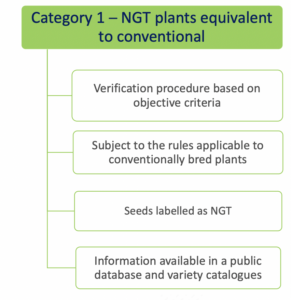

- Category 1 NGT plants: these plants are considered equivalent to conventionally bred plants based on the criteria in Annex I

of the NGT Regulation and as such do not need to undergo complete GMO risk assessment. Instead, a notification to a national GMO authority or to EFSA is sufficient;

of the NGT Regulation and as such do not need to undergo complete GMO risk assessment. Instead, a notification to a national GMO authority or to EFSA is sufficient;

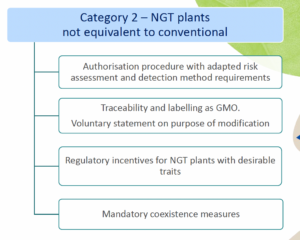

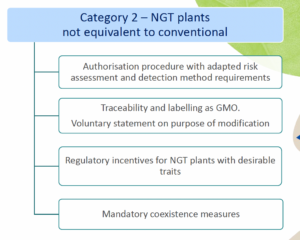

- Category 2 NGT plants: these plants are considered as GMOs and as such are subject to the GMO rules for authorization, traceability and labeling, however according to a modified system of more targeted risk analysis.

In addition to NGT plants, these regulations also apply to NGT products: that includes foods with ingredients made from such plants. This is why this proposed Regulation is so relevant for innovative food business operators.

In addition to NGT plants, these regulations also apply to NGT products: that includes foods with ingredients made from such plants. This is why this proposed Regulation is so relevant for innovative food business operators.

As mentioned above, for category 1 NGT plants, a notification procedure takes place and for category 2 NGT plants a full swing risk assessment. Both procedures involve a substantive assessment of whether plant material produced using targeted genetic techniques complies with the specifically developed rules for risk assessment. It is expected that the procedure for category 1 NGT products can be completed within a year, while the permit process for category 2 NGT foods is actually identical to that for regular GMOs. An innovation is that the NGT Regulation provides certain incentives for specific category 2 NGT foods that should speed up or simplify the assessment process.

Transparency regarding genetic engineering

Producers of organic products and advocacy organizations are concerned that, based on the NGT Regulation, genetically engineered food is walking into stores undetected. But is this concern justified? Based on the current text of this Regulation, both category 2 and even category 1 NGT products are excluded from organic production. Indeed, in the consultation process leading up to the NGT Regulation, the freedom of choice of consumers to buy food containing or not containing GMOs appeared to be an important issue. At the same time, the European Parliament considers the prohibition for organic farmers to use conventional-like category 1 NGT’s neither science-based, nor politically justifiable. It therefore calls in its draft report to create a fair level playing field and to only ban category 2 NGT plant material from organic production.

Category 1 NGT products listed in public database?

Whether or not allowed in organic production, there is no specific labeling requirement for Category 1 NGT products (Q 11 from EC Q&A). However, plant material with Category 1 NGT status must be included in a public database, expected to be similar to the Novel Food consultation database. In the Commisson’s proposal, plant reproduction material with Category 1 NGT status must additionally be labeled as such, with the identification number of the plant from which it is derived. At the level of production, this would provide an extra safeguard for distinguishing between conventionally grown crops and crops in which genetic engineering has been used. The European Parliament is however critical about this additional requirement in its draft report. It considers such discriminatory since category 1 NGT plants are conventional-like. According to the European Parliament, transparency and consumer choice are sufficiently ensured by disclosure in a public database. Therefore, even if the modifications proposed by the European Parliament will stand, there is no reason to believe that foods produced using CRISPR-Cas9 could go completely unnoticed.

Conclusion

With current changes in climate and constraints on available agricultural land with a growing world population, plant harvests will come under increasing pressure. NGTs are expected to meet the need to better equip plants for such challenges. The proposed NGT Regulation aims to simplify and thereby accelerate market access for such technology. For category 1 NGT products, except for a few open ends, this premise seems feasible in practice. A huge improvement with respect to current legislation is that the nature of the genetic change is decisive for risk evaluation, not the technique by which it is produced (product-based vs. process-based approach). For category 2 NGT products, market access is not expected to become much simpler based on the current proposal. Nevertheless, this proposal looks hopeful for plant innovations and thus for our food products of tomorrow. Also, there seems to be sufficient transparency to distinguish between crops produced with and without genetic engineering. My very bald hope would be that based on positive experiences with this regulation, the scope of this regulation will be extended to other fields, such as cellular agriculture and/or fermentation-based products. We will continue to follow closely how this legislation will develop.

Source images

- How CRISPR works: EU Parliament briefing on Plants produced by new genomic techniques

- Category 1 NGT plants: PPT DG Santé on Farm to Fork Strategy presented during EFFL Conference on 19 October 2023.

- Category 2 NGT plants: idem (2)

Thanks to my colleagues Jasmin Buijs and Max Baltussen for their valuable feed-back.

Posted: May 9, 2018 | Author: Jasmin Buijs | Filed under: Authors, Information, organic |

The organic sector has developed from a niche market to one of the most dynamic sectors of EU agriculture. To recall some numbers provided by the European Commission, the amount of land used for organic farming grows at around 400,000 hectares a year. The organic market in the EU is worth around €27 billion, some 125% more than ten years ago. The EU encourages more farmers into the organic sector and aims to increase consumers’ trust in certified organic products to further boost those numbers. For some background on the regulatory framework, we refer to our earlier blogpost on the Organics Regulation. As already announced in that post, the current Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007 needs an update as it is based on practices of over 20 years ago. The first proposal for a new EU Regulation on organic production dates back to 2014. Last month, the European Parliament Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development gave green light to the new Organic Regulation. This new regulation aims to guarantee organic production throughout the supply chain by phasing out the many exemptions that are allowed under the current Regulation, such as the use of non-organic seeds as further covered below. In other words, the new regulation shifts from an à la carte system of exceptions to a set menu of harmonized rules. This contribution sets out the most important changes by answering relevant questions in the light of the new Organic Regulation.

The organic sector has developed from a niche market to one of the most dynamic sectors of EU agriculture. To recall some numbers provided by the European Commission, the amount of land used for organic farming grows at around 400,000 hectares a year. The organic market in the EU is worth around €27 billion, some 125% more than ten years ago. The EU encourages more farmers into the organic sector and aims to increase consumers’ trust in certified organic products to further boost those numbers. For some background on the regulatory framework, we refer to our earlier blogpost on the Organics Regulation. As already announced in that post, the current Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007 needs an update as it is based on practices of over 20 years ago. The first proposal for a new EU Regulation on organic production dates back to 2014. Last month, the European Parliament Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development gave green light to the new Organic Regulation. This new regulation aims to guarantee organic production throughout the supply chain by phasing out the many exemptions that are allowed under the current Regulation, such as the use of non-organic seeds as further covered below. In other words, the new regulation shifts from an à la carte system of exceptions to a set menu of harmonized rules. This contribution sets out the most important changes by answering relevant questions in the light of the new Organic Regulation.

Which products are covered under the new Organic Regulation?

Similar to the current Organic Regulation, the new Organic Regulation applies to live and unprocessed agricultural products, including seeds and other plant reproductive material and processed agricultural products used as food and feed. Processed products can be labelled as organic only if at least 95% by weight of their ingredients of agricultural origin are organic. Unlike the current Organic Regulation, the new Organic Regulation also covers certain other products closely linked to agriculture. Those products are listed in Annex I and include, among others, salt, essential oils, cork, cotton, and wool. Other products may be added in future.

To what extent can non-organic seeds still be used?

Derogations that allow non-organic seeds to be used in organic production will expire in 2035. A couple of measures will be taken to increase the organic seed supply and to help it meet high demands before that time. First of all, Member States shall establish a database of organic plant reproductive material as well as national systems that connect organic farmers with suppliers of organic reproductive material. Secondly, the use non-organic seeds may temporarily remain allowed if the collected data demonstrates insufficient quality and quantity of the organic reproductive material. Also, to meet the demands of organic seeds, organic heterogeneous material is explicitly allowed for in Article 13 of the new Organic Regulation and production criteria for organic varieties are adapted taking into account the specific needs and constraints of organic production. The derogations may be phased out earlier than 2035 or extended based on a report due in 2025, which will examine the situation of plant reproductive material on the market.

Are mixed farms still allowed under the new Organic Regulation?

While the initial proposal of the Commission proposed to ban the production of organic products and conventional products at the same farm, mixed farms continue to exist under the new Organic Regulation. Mixed farms are allowed provided that the two production activities are effectively separated into clearly distinct production units. This means, among others, that inputs for production as well as the final products must be separated to avoid contamination and potential fraud. Also, the two production activities should involve different livestock species and plant varieties.

What measures must be taken to avoid contamination from non-authorized substances?

EU thresholds for conventional products automatically apply to organic ones too. Stricter thresholds for non-authorized substances in organic products are not introduced. This would include high costs, especially for small farmers, to control for example contamination from neighbouring conventional farming. Instead, food business operators are obliged to take precautionary measures to avoid contamination. The responsibility and accountability of organic producers will thus be emphasized. Final products are not allowed to bear the organic label when the contamination was deliberate or caused by irresponsible food business operators that failed to take precautionary measures. Meanwhile, Member States remain at liberty to set specified thresholds for non-authorized substances in organic products, provided that these national rules will not affect the trade of organic products that are legally placed on the market in other Member States. Based on a report due by the end of 2024, anti-contamination rules and national thresholds may be further harmonized in future.

How does the new Organic Regulation ensure the high quality of organic products?

Rather than moving all the control provisions into the regulation on official controls for food and feed, as initially proposed by the Commission, specific rules will apply to the control of organic farming. Organic production refers to the use of production methods that contribute to the protection of the environment, animal welfare, and rural development. Risk-based checks will therefore not be limited to final products but take place along the supply chain to guarantee that organic products are truly organic. Physical on-site checks will take place at least annually; the on-site check may be reduced to once every two years if the food business operator has been fully compliant for three years. In the Netherlands, those inspections are carried out by SKAL as the the designated Control Authority responsible for the inspection and certification of organic companies.

What does the new Organic Regulation mean for products imported into the EU?

Under the current Organic Regulation, organic products produced in third countries are allowed on the EU market when the organic standards of the exporting country are similar to EU rules. This means that organic products are in fact regulated by over 60 different standards. Under the new Organic Regulation, all imported products will have to comply with EU standards. Taking into account the date of application of the new Organic Regulation as well as the transitional period granted for imported products, this rule will only apply as from 2026. Moreover, certain exceptions are introduced to avoid disruptions of supply on the EU market. First of all, the Commission is empowered to grant specific authorization for the use of products and substances in organic production in third countries with specific climatic and local conditions, which therefore cannot comply with the new requirements. This exception also applies to organic production in the EU’s outermost regions, such as the Nordics. Secondly, equivalent production methods in third countries could be recognised under trade agreements.

Conclusion

The new Organic Regulation promises to further boost EU organic production. Measures to increase the supply of organic seeds and animals, allowing mixed farming, and no harmonized thresholds for non-authorized substances aim to attract more farmers into organic production. Meanwhile, measures are taken to increase consumers’ trust in organic products, such as through risk-based checks along the supply chain and the switch from the principle of equivalence to an EU single set of rules for imported products. We expect this to be a major improvement for the algae sector, that suffers unfair competition from Asian countries, where organic standards are not necessarily the same as in the EU.

It takes some more years to see to what extent the Regulation will live up to its promises. While the Regulation itself only becomes applicable from 2021, many rules are subject to further implementation depending on the development of the sector. This illustrates the dynamic character of the organic sector, which creates many opportunities for food business operators active in this field.

Posted: October 4, 2016 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Food, organic |

Algae are in the spotlight as a sustainable source of protein, fibres and fatty acids. A form of sustainability is found in organic production. Besides sustainable, consumers perceive organic products as healthy and safe. Therefore producers of microalgae would like to use the organic logo. We previously reported on this topic in an earlier post this year. This post reports what is new in the regulatory framework. It furthermore elaborates on the legal and practical obstacles that algae producers currently encounter with respect to the use of the organic logo, as regulated here, and it explores potential solutions.

Algae are in the spotlight as a sustainable source of protein, fibres and fatty acids. A form of sustainability is found in organic production. Besides sustainable, consumers perceive organic products as healthy and safe. Therefore producers of microalgae would like to use the organic logo. We previously reported on this topic in an earlier post this year. This post reports what is new in the regulatory framework. It furthermore elaborates on the legal and practical obstacles that algae producers currently encounter with respect to the use of the organic logo, as regulated here, and it explores potential solutions.

Various species of algae

The term “algae” covers both macro- and microalgae. Macroalgae – popularly called seaweed – can be seen with the naked eye. Examples include nori (sushi sheets), sea lettuce and kelp. Microalgae are single-celled organisms up to 50 micrometres in size, and thus not or hardly visible to the naked eye. There are many different species of microalgae, of which Chlorella and Spirulina are the best known. Both species have a history of safe use as application in food for human consumption. This means that the Novel Food legislation does not preclude the use of these algae in foodstuffs.

Organic certification

For a general description of the content of the EU Organic Regulation, we refer to our previous post. In essence, it comprises an overall system from farm to fork for the production of foodstuffs including micro and macroalgae. Furthermore, it provides for the possibility that so-called compliant products imported into the EU from recognized countries may be marketed as organic when certain conditions are met. The bottleneck so far was that the EU Organic Regulation did not provide for specific rules for the production of microalgae. This situation was partly remedied by the so-called Interpretative Note that the Commission published in July 2015. This document accepted the application of private standards recognized or accepted by the Member States, provided that they did not impose additional measures upon products originating from other Member States. Furthermore, it was established that until the moment that detailed production rules for micro algae would be determined, the production of microalgae must comply with the rules applicable to the production of either plants or seaweed. As a consequence, there was no consensus about the exact production standards for organic labelling of microalgae produced in Europe. At the same time it was – and is – possible for organically produced microalgae in third countries to be imported as such in the EU. Because of this situation European microalgae products are one-nil down.

Further regulations

In April this year, the Commission adopted a new Regulation changing the executive provisions of the EU Organic Regulation. In this 2016 Regulation, the Commission stipulates that to date no detailed production rules have been defined for microalgae used as food. Because of this it is still unclear what production rules govern the cultivation of microalgae. Therefore it should be clarified that detailed production rules that apply to the production of seaweed also apply to the production of microalgae for use as foodstuff. This clarification has been obtained by extending the production rules for seaweed applicable to feed, based on an amendment of the executive provisions of the EU Organic Regulation, also to food. The 2016 Regulation will enter into force on May 7, 2017.

Practical problems

Are thus all obstacles removed to organic certification of microalgae produced in the EU? Unfortunately not, because microalgae cannot be compared with seaweed just like that; as seaweed is a macroalgae. Although there are similarities between growing micro and macro algae, the harvest thereof is different. As to the similarities: both macro and micro algae need dissolved minerals and CO2 to grow since they do not break down manure automatically. Therefore, fertilizer and manure derivative products are usually added to the water in order to make the minerals contained in the fertilizers bioavailable to the algae. However, the addition of fertilizer or manure derivative products to an algae culture results into the harmful organisms present therein, such as toxins and heavy metals, to mix with the algae. Products made from algae to which manure or manure derivatives solutions are added, may therefore constitute a very high food safety risk. As to the differences between macro and micro algae: in the harvest of seaweed only the macro algae are harvested. The organisms and bacteria present in the water remain there and the product can be cleaned from harmful substances. However, this is not possible with the harvest of microalgae because of their small diameter. As a result, the bacteria, fungi and other organisms present in the culture are harvested as well and partly end up in the final product. The food safety of such products is questionable.

Risks of open cultivation systems

The vast majority of micro-algae are being cultivated in open ponds. These systems are afflicted by external influences. For that reason, a pond is continuously contaminated with undefined organisms such as bacteria, fungi, aquatic insects, toxins and even faeces. A method to inhibit this unwanted growth is the use of high concentrations of iodine. Algae products from such systems often contain very high concentrations of iodine and they therefore constitute a potential health risk. Nevertheless, third countries other than recognized countries do certify these products as being organic. As a matter of fact, they are marketed outside the system of similar products and recognized countries. This forms a troublesome form of competition for micro algae produced in the EU.

Advantages of closed systems

In closed systems, there are hardly any external influences. In these systems, the entire process of cultivation up to and including harvest can be closely monitored. In the unfortunate situation that any contamination occurs, this can promptly be detected and appropriately responded to. This way of cultivation of algae excludes the risk of unwanted organisms in the final product. However, in order to be able to grow algae under these conditions, the minerals required for the start of growth of the algae have to be added in a different way than in the open nature. Production of microalgae in closed systems therefore usually takes place by the addition of dissolved minerals.

Addition of minerals hinders organic certification

In organic production only a limited number of permitted minerals can be used. When an algae producer uses minerals that are not on the list of permitted substances, he cannot certify his products as being organically grown for the time being. From that perspective, it is important to mention that for some minerals, such as nitrogen and phosphate, there are no suitable natural alternatives or sources available. Mineral salts extracted from mines for instance are not considered safe for use in food. Therefore, currently isolated variants, of which the food safety is guaranteed, are used. Even if an algae producer could apply for admission of these minerals on the list, this has a downside. Normally, these minerals form an integral part of a specific production process containing proprietary information that cannot be disclosed by an algae producer just like that. When filing a request for authorization of minerals in organic production, the probability is low that confidential elements of the relevant production processes remain confidential in such an application.

Possible solutions

We see two possible solutions to the problems identified above. Firstly, we expect that when the confidentiality of so-called proprietary data in an application for authorization of certain minerals in organic production could be ascertained for a minimum period, this would give a big boost to the organic cultivation of microalgae. Such regimes also exist for dossiers to be filed for the authorization of Novel Foods and of health claims, so this is not uncommon in food law. Secondly, a so-called grace period for substances currently used in closed culture systems could provide a solution. This grace period would need to apply until there is an acceptable functional alternative available for the envisaged substances in terms of quality, quantity and price. In both cases, of course, food safety is paramount. This means that the added minerals should be proven to be food-safe. Application of the proposed solutions would enable EU producers of microalgae the opportunity to use the EU organic logo for food-safe algae products. This would be a win-win for consumers and producers.

This post is based on a Dutch article that was co-written by the Dutch algae manufacturer Nutress, belonging to the Phycom group. It was published in the September 2016 issue of VMT, a Dutch magazine for the food business. The picture was kindly provided by Nutress, who owns the copyright thereof.

Posted: January 26, 2016 | Author: Sofie van der Meulen | Filed under: Enforcement, Food, organic |

This contribution aims to provide you with a brief overview of the EU Organic legislation and recent developments. Being able to market products as ‘organic’ could be a plus for the food business operator (FBO) as the demand for sustainable production and organic food increases. This contribution focuses on the EU-system of organic certification of food products and will specifically look at the position of organic microalgae manufactured in the EU. Under the current legislative framework, these could not be marketed as such in the EU. This has changed since an interpretative note of the Commission of last summer. If you are an FBO interested in marketing organic microalgae, this for sure is of interest to you.

This contribution aims to provide you with a brief overview of the EU Organic legislation and recent developments. Being able to market products as ‘organic’ could be a plus for the food business operator (FBO) as the demand for sustainable production and organic food increases. This contribution focuses on the EU-system of organic certification of food products and will specifically look at the position of organic microalgae manufactured in the EU. Under the current legislative framework, these could not be marketed as such in the EU. This has changed since an interpretative note of the Commission of last summer. If you are an FBO interested in marketing organic microalgae, this for sure is of interest to you.

Organics Regulation – scope

First of all, what is ‘organic production’? According to recital 1 of the Organics Regulation organic production is: “(…) an overall system of farm management and food production that combines best environmental practices, a high level of biodiversity, the preservation of natural resources, the application of high animal welfare standards and a production method in line with the preference of certain consumers for products produced using natural substances and processes” (see also the definition in Article 2(a)).

What is covered by the Organics Regulation? Only agricultural plants, seaweed, livestock, aquaculture and animals are regulated under the Organics Regulation. For example, if an FBO wants to produce organic seaweed, all the processes have to be in compliance with the Organics Regulation. This approach is known as the ‘farm to fork approach’, which means every step in the production process throughout the supply chain has to comply with the Organics Regulation.

Organics Regulation – structure

The Organics Regulation has a layered structure. The following three layers of provisions can be found:

- General production rules (articles 1, 7 – 10), which apply to all forms of organic production.

- Production rules for different sectors (articles 11 – 21): general farm production rules and production rules for specific categories of products and production rules for processed feed and food.

- Detailed production rules (article 42).

If there are no production rules for the sector (layer 2), only the general production rules (layer 1) apply.

Organics certificate

Compliance with the Organics Regulation has to be demonstrated by obtaining certificates from a certification body. (See the following link for a list of competent certification bodies in different Member States). In the event a certification body audits the FBO marketing organic products and it encounters violations of the Organics Regulation, it can decide to block certain non-compliant batches of products pending an investigation. Depending on the outcome, the certification body can subsequently decide to withdraw the certificate. If the certificate is withdrawn, the FBO is no longer allowed to market the products as ‘organic’. In case of severe violations, the competent authority may impose a recall of the products. In the Netherlands, Skal Biocontrole is the designated Control Authority responsible for the inspection and certification of organic companies in the Netherlands, within the context of Regulations: (EC) Nr. 834/2007 (Organics Regulation), (EC) Nr. 889/2008 and (EC) Nr. 1235/2008 (import of organic products from third countries). Skal monitors the entire Dutch organic chain on behalf of the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs.

The EU organic logo

The EU logo is regulated in a separate Commission Regulation. The main objective of the European logo is to make organic products easier identifiable by the consumers. Furthermore it gives a visual identity to the organic farming sector and thus contributes to ensure overall coherence and a proper functioning of the internal market in this field. For practical information regarding the EU logo, see this link and this link.

Organic microalgae

Prior to July 2015, FBO’s could not obtain an organic certification for microalgae manufactured within the EU for the use in their food products. FBO’s from third countries (non-EU) could market their products in the EU based on either the import procedure as set out in Article 33 (2) (import from recognised third countries) or the import procedure laid down in Article 33 (3) of the Organics Regulation (import of products certified by recognised control bodies). The strange situation was created where ‘organic’ microalgae could only be imported into the EU and not be produced within the EU.

How come? All agricultural products were considered to fall within one of the different production rules for specific categories of products (layer 2) and microalgae for food production were not included. Furthermore, detailed EU production rules for microalgae were absent (layer 3). (Article 42 (2) Organics Regulation).

The Interpretative note of the European Commission (Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development) of July 2015 opened up the possibility for companies in both EU Member States and third countries to produce microalgae, which can be marketed as ‘organic’ and carry the EU organic logo. Both the existing production rules for plants (Article 12 Organics Regulation) and seaweed (Article 13 Organics Regulation) could be suitable for microalgae.

‘Until an implementing act adopted on the basis of Article 38 (of Regulation 834/2007) has clarified the situation, operators producing organic micro algae (except for use as feed for aquaculture) have therefore to comply with the general production rules, which apply to all forms of organic production (“layer 1”) and with the production rules for the sector of plants or seaweed (“layer 2”).’

The use of microalgae as feed for aquaculture is not covered in the Interpretative note, as microalgae as feed are already subject to the detailed production rules. The rules for the collection and farming of seaweed apply according to Article 6a of Commission Regulation (EC) No 889/2008.

The interpretation opens up the possibility to certify microalgae to be used as food (or as an ingredient in food) as being organic. When an implementing act will be published and enter into force is still unknown. A proposal for a new Regulation repealing the Organics Regulation has been published. On 5 November 2015 a report from the Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development on the proposal was published, introducing 402 amendments. The current status of the proposal is available through this link.

Aside from enforcement by a national control authority in case of non-compliance with the Organics legislation, consumers and other interested parties often also have the possibility to lodge a complaint relating to advertising of organic products. However, advertising of (organic) products is a topic to be covered in another contribution on Food Health Legal. Stay tuned!

This contribution aims to provide you with a brief overview of the EU Organic legislation and recent developments. Being able to market products as ‘organic’ could be a plus for the food business operator (FBO) as the demand for sustainable production and organic food increases. This contribution focuses on the EU-system of organic certification of food products and will specifically look at the position of organic microalgae manufactured in the EU. Under the current legislative framework, these could not be marketed as such in the EU. This has changed since an interpretative note of the Commission of last summer. If you are an FBO interested in marketing organic microalgae, this for sure is of interest to you.

This contribution aims to provide you with a brief overview of the EU Organic legislation and recent developments. Being able to market products as ‘organic’ could be a plus for the food business operator (FBO) as the demand for sustainable production and organic food increases. This contribution focuses on the EU-system of organic certification of food products and will specifically look at the position of organic microalgae manufactured in the EU. Under the current legislative framework, these could not be marketed as such in the EU. This has changed since an interpretative note of the Commission of last summer. If you are an FBO interested in marketing organic microalgae, this for sure is of interest to you.