Posted: April 24, 2024 | Author: Jasmin Buijs | Filed under: Advertising, Authors, Food, Food Supplements, Health claims, Information, Nutrition claims |

The International Probiotics Association Europe (IPA Europe) is calling for harmonized use of the claim ‘probiotics’ in the EU. Aforementioned term is generally considered an unauthorized health claim under the EU Claims Regulation. Nevertheless, an increasing number of EU member states allows the use of this claim under certain conditions. This blogpost dives into the regulatory status of probiotic claims in different EU member states and the latest developments in this area.

The International Probiotics Association Europe (IPA Europe) is calling for harmonized use of the claim ‘probiotics’ in the EU. Aforementioned term is generally considered an unauthorized health claim under the EU Claims Regulation. Nevertheless, an increasing number of EU member states allows the use of this claim under certain conditions. This blogpost dives into the regulatory status of probiotic claims in different EU member states and the latest developments in this area.

When entering the keyword ‘probiotic’ in the EU Health Claims Register, one is confronted with over 100 rejected health claims. Over the past years, this has led to the question whether the term ‘probiotic’ should be allowed under certain conditions, and has resulted into divergent policies in different EU member states. To protect both the food industry (against unfair competition) and the consumer (against misleading information), these divergent policies are reason for IPA Europe to call for a harmonized framework.

Czech Republic, Northern Ireland and France

Although EU member states generally consider ‘probiotics’ to be an unauthorized health claim under the EU Claims Regulation, some EU member states take a different approach. ‘Probiotics’ is for example considered a nutrition claim in the Czech Republic. Such claim is allowed if the conditions set forth in the EU Claims Regulation are met. This means, amongst others, that the good bacteria in question are present in the food in an amount that, according to generally accepted scientific evidence, causes the claimed beneficial effect. By contrast, in France and Northern Ireland, the term ‘probiotics’ can be used as a general, non-specific health claim that is allowed in combination with the authorized health claim “live cultures in yoghurt or fermented milk improve lactose digestion of the product in individuals who have difficulty digesting lactose”.

Italy

Italy takes the view that the term ‘probiotics’ does not meet the definition of a health claim and therefore falls outside the scope of the EU Claims Regulation. Italy supports this view by EFSA’s conclusion that probiotic colonization in the intestinal flora (without further specification of bacterial species or strains) is insufficient evidence to substantiate a beneficial effect on human health. In other words, no link between probiotics and health can be demonstrated, for which reason ‘probiotics’ cannot be considered a health claim. Aforementioned reasoning is however not a free pass to unconditionally use the term ‘probiotics’ in Italy. Instead, the following conditions must be met if and when using this term: (i) safety for human consumption, (ii) a history of use for the benefit of the intestinal flora, and (iii) presence of the relevant bacteria in the food in live form and in an adequate quantity until end of shelf life.

Denmark and Spain

In Denmark, the term ‘probiotics’ can be used based on a different legal ground, namely as a mandatory category designation under the EU Food Supplements Directive. In France, such is also possible. Indeed, Article 6(3)(a) of the EU Food Supplements Directive requires that the labeling of the food supplement shall bear “the names of the categories of nutrients or substances that characterize the product or an indication of the nature of those nutrients or substances”. In Spain, the claim ‘probiotics’ is allowed thanks to the principle of mutual recognition. Based on this principle, a product lawfully marketed in one EU member state must also be accepted on the market of another EU member state. Since probiotic claims are therefore allowed on the Spanish market for products from other EU member states, banning the term ‘probiotics’ at national level would discriminate against national producers. Therefore, both food products produced within Spain and those produced outside of the country can bear the claim ‘probiotics’.

Netherlands

In the Netherlands – just like in Denmark and France – the term ‘probiotics’ can be used as a category designation for food supplements. This Dutch practice is laid down in the Guideline Document on the EU Claims Regulation by the Dutch Health Advertising Knowledge and Advice Council (in Dutch: Keuringsraad). An earlier version of the Nutrition and Health Claims Manual by the Dutch Food Safety Authority (in Dutch: NVWA Handboek Voedings- en Gezondheidsclaims) also explicitly mentioned this possibility. Such is now longer mentioned in the latest version of the Nutrition and Health Claims Manual, which can be explained by the fact that ‘probiotics’ as a category designation for food supplements is not a nutrition or health claim.

Although claims that further elaborate on the health effect of probiotics (sporadically) occur on the Dutch (online) market, these are not allowed. Whether the expression “increases the good bacteria in the intestinal flora” (without using the term ‘probiotics’) is acceptable in the Netherlands, is yet unclear. Yakult uses this expression to advertise its fermented milk drink. The Dutch Health Advertising Knowledge and Advice Council would not allow this expression in the context of its preventive supervision in the context of food supplements, because this expression in effect creates a link between the food product and health. If the NVWA has however a different opinion on this and does consider aforementioned expression possible, then other food businesses can take advantage of this too. The call for harmonized uses of the term ‘probiotics’ by IPA Europe, about which more below, can possibly contribute to the acceptance of such expression at national level.

”Probiotics’ not a health claim”

As demonstrated above, various EU member states have introduced national rules on the use of the term ‘probiotics’. As a result, IPA Europe believes that the European Commission’s position that ‘probiotics’ implies a health benefit and is therefore a(n unauthorized) health claim no longer holds water. Instead, IPA Europe advocates qualifying the claim ‘contains probiotics’ as a nutrition claim, just like ‘contains vitamins and minerals’ and ‘contains fiber’. Aforementioned substances may have beneficial nutritional properties, but no specific health benefit is claimed. To strengthen its argument that ‘probiotics’ is not a health claim, IPA Europe explains that the term is not sufficiently precise to substantiate the claimed health benefit under reference to an EFSA guidance document published in 2016.

Call for harmonized use of the term ‘probiotics’

According to IPA Europe, ‘probiotics’ is therefore not a health claim and does not require authorization under the EU Claims Regulation. At the same time, it emphasizes the need for clear rules on the use of the claim as this contributes to a fair competitive environment for food businesses and helps consumers to make informed choices. In December 2023, IPA Europe therefore called for a clearly defined framework for the use of the term ‘probiotics’ in the EU. IPA Europe recommends the following four criteria for consistent use thereof:

- characterization of the species level and identification of at strain level;

- the probiotic strain must be safe for the intended use, e.g. based on the QPS list;

- the probiotic status should be scientifically documented; and

- the probiotic strains must be alive in the product and in a sufficient amount up to the end of shelf-life.

Final comment

The EU knows a fragmented regulatory landscape when it comes to the use of the term ‘probiotics’. Despite IPA Europe’s efforts for a harmonized approach throughout the EU, we will need European legislation or a ruling from the European Court of Justice to have the same rules in all EU member states. For now, the term ‘probiotics’ is (fortunately) not completely banned in the Netherlands and neither in quite a few other EU Member States.

This blogpost has also been published in Dutch at VMT.nl.

Posted: December 1, 2022 | Author: Jasmin Buijs | Filed under: Advertising, Enforcement, Food, Food Supplements, Health claims |

Intro

Food businesses operators that make medical claims for their products in the Netherlands can be fined for doing so under food law. However, they also run the risk of being fined under the Dutch Medicines Act (in Dutch: “Geneesmiddelenwet”), in which case much higher fine amounts apply. The latter sometimes provokes surprise and outrage. Based on three recent rulings, we see a positive trend, which is explained below.

Drug definition

In principle, a medicinal product cannot be sold in the Netherlands without an authorization. Advertising a medicinal product that has not been authorized is prohibited as well. If a product is classified as such and sold without a license, the seller risks a hefty fine.

In principle, a medicinal product cannot be sold in the Netherlands without an authorization. Advertising a medicinal product that has not been authorized is prohibited as well. If a product is classified as such and sold without a license, the seller risks a hefty fine.

The legal definition of the term medicinal product and the corresponding authorization requirement can be found in the Dutch Medicines Act, which is based on the European Directive 2001/83/EC (the “Medicinal Product Directive”). The Medicinal Product Directive provides two criteria for the definition of a medicinal product: qualification by presentation and qualification by function. If a product meets one of these two criteria, it is classified as a medicinal product. The aforementioned criteria are further elaborated in case law.

Qualification by function

A product is a medicinal product by function (see the Hecht-Pharma judgment) if it can be administered to cure or prevent disease, diagnose or otherwise affect a person’s bodily functions. Of particular importance here are the composition and properties of the product, the method of use, the extent of distribution of the product, the consumers’ familiarity with the product and the health risks associated with its use.

Qualification by presentation

When applying the presentation criterion (see the Van Bennekom judgment), consideration is – unsurprisingly – given to whether a product should be regarded as a medicinal product on the basis of its presentation. It is not necessary that the product is expressly indicated or recommended as a medicinal product. The presentation criterion is already met if the manner of presentation gives the average consumer the impression that the product has a medicinal effect. The form in which the product is presented may give an indication for this, especially in the case of tablets, pills and capsules.

In particular the presentation criterion poses a risk to food companies. If they (unintentionally) make a medical claim in respect of their product, the presentation criterion may result in this product being classified (also) as a medicinal product by the Dutch Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (“NVWA”). In that case, the NVWA may issue a fine under the Dutch Medicines Act. The starting point for such fine is €150,000, which is then differentiated based on the Policy rules of the Dutch Ministry of Health 2019. Even if the product also falls within the legal definition of food, the Dutch Medicines Act may apply simultaneously. The foregoing follows from the so-called hierarchy provision embodied in article 2.2 of the Medicinal Products Directive, which has been implemented into Dutch law as well. On the basis of this hierarchy principle, the Dutch Medicines Act is applicable if there is any doubt about the applicable product category. The result of this provision is that even a seller of coconut oil can receive a fine under the Dutch Medicines Act.

New trend in enforcement of medical claims?

Dutch case law gives numerous examples of products being classified as medicinal products by courts based on (solely) the presentation criterion. Recently, three court rulings have been rendered which give reason to assume that there is a new trend in case law. These are a ruling of the District Court of Oost-Brabant of March 25, 2022, and two (materially identical) rulings of the District Court of The Hague of June 28, 2022, regarding food supplements and follow-on milk, respectively.

The first case concerns the sale of dietary supplements, for which medical claims were made. The NVWA therefore classifies these supplements as medicinal products based on the presentation criterion and imposes two fines under the Dutch Medicines Act (both for sale and for advertising an unregistered medicinal product). The seller’s defense is that the Dutch Medicines Act should be interpreted in accordance with the Medicinal Product Directive and that it follows from there that the contested decision of the NVWA is based on an incorrect legal basis.

The court agreed with this argumentation, referring to the amendment of the Medicinal Product Directive of 2004. The court deduces from the preamble to the amendment that the Medicinal Product Directive does not apply if there is no doubt that a product clearly exclusively belongs to another product category, such as food or food supplements. The court ruled that this was indeed the case for the specific circumstances that were under discussion. The products clearly fall under the category of food supplements and therefore solely food law applies. The court confirms that the Dutch Medicines Act must, after all, be interpreted in accordance with the Medicinal Product Directive. The court therefore does not proceed testing the medical claims made against the presentation criterion based on drug legislation at all.

The court agreed with this argumentation, referring to the amendment of the Medicinal Product Directive of 2004. The court deduces from the preamble to the amendment that the Medicinal Product Directive does not apply if there is no doubt that a product clearly exclusively belongs to another product category, such as food or food supplements. The court ruled that this was indeed the case for the specific circumstances that were under discussion. The products clearly fall under the category of food supplements and therefore solely food law applies. The court confirms that the Dutch Medicines Act must, after all, be interpreted in accordance with the Medicinal Product Directive. The court therefore does not proceed testing the medical claims made against the presentation criterion based on drug legislation at all.

Clearly food-only

The above ruling raises the question when a product is “clearly exclusively” a food and what aspects of the product are important in this respect. Indications for this can be found in the two recent decisions of the District Court of The Hague regarding specific food products for toddlers, namely follow-on formula. In its assessment of whether the follow-on formula in question could be a medicinal product by presentation, the court determined that such qualification is not obvious with regard to products sold in supermarkets and drugstores. Another factor in this case was that the detailed information about the follow-on formula, on the basis of which the Dutch Ministry of Health (the counterparty in the cases at stake) believed it to be a medicinal product by presentation, could only be found on the seller’s website.

Conclusion

Based on the rulings discussed, we signal a trend that judges are halting the current practice of enforcement of prohibited medical claims for food products based on the Dutch Medicines Act. The discussed rulings make clear that (prohibited) health claims for food supplements and for other food products such as follow-on formula should be assessed on the basis of the Food Information for Consumers Regulation (the “FIC Regulation”), and not via the presentation criterion based on the Dutch Medicines Act. In our opinion this is justified, because since the FIC Regulation became applicable, food law is specifically set up to do so. We are very curious to see whether the trend initiated above will be followed by other courts. Although it follows from a ruling of the District Court of Zeeland-West-Brabant of 21 October, 2022, that this is not yet the case, we trust this will only be a matter of time.

The above does however not mean that food business operators would be allowed to make medical claims for their products. Also, the FIC Regulation contains a ban on medical claims for food products and the Nutrition and Health Claims Regulation sets forth a strict regime for authorized health claims. Having said that, fines following a violation of food legislation are far lower than fines based on the Dutch Medicines Act. On balance, food companies are therefore better off with fines based on food legislation.

This blogpost is written by Max Baltussen, Karin Verzijden and Jasmin Buijs.

The authors want to acknowledge Ebba Hoogenraad and Irene Verheijen for sharing the case law discussed here.

Posted: January 11, 2021 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Enforcement, Food, Food Supplements, Nutrition claims |

Introduction

Introduction

Last week I received a call from an entrepreneur who wanted to know what requirements he had to bear in mind when distributing food supplements from Finland to other EU Member States. I told him about the language requirements for mandatory food information. I also informed him that the allowed level of vitamins and minerals could differ from Member State to Member State. Furthermore, in some countries a so-called notification system for market access has been put in place, whereas in others, no such system applies. Finally, I informed him that there is no harmonised approach on prohibited substances in the EU either. In fact, he was quite surprised to learn about all this, as he thought food supplements to be subject to the principle of free circulation of goods in the internal market. Is not that correct? Yes, it is. However, as follows from the above, a number of exceptions apply to this principle. This blogpost explains what is being done to achieve more harmonisation in the food supplements market.

Food supplements: what are they in fact and what happens in practice?

According to the Food Supplements Directive, food supplements are meant to supplement the normal diet. They are concentrated sources of nutrients or other substances having a nutritional or physiological effect that are mostly sold in the form of pills or powders. While nutrients are vitamins and/or minerals, such other substances are, for example, amino acids, glucosamine or certain substances contained in herbs or plants. What we see in practice, is that more and more consumers use food supplements not only to supplement their diet, but for a targeted health effect. Increasing concentration or improving sport achievements are two examples thereof. Another trend is that a broad number of food supplements is nowadays offered for sale online. As many of them come with striking health claims, it is not always sufficiently clear for consumers what they are actually buying. In these COVID-times, many supplements claimed for example to boost the immune system without meeting the specific requirements for such claim. This may create a dangerous situation if and when dangerous substances are involved.

Food supplements: a boosting market but not without risks

The market of food supplements in the Netherlands alone was valued in 2019 by Neprofarm at € 143 million. In that same year, the Netherlands pharmacovigilance centre Lareb received 165 notifications of adverse reactions regarding food supplements. Even worse, the Netherlands Intoxications Information Centre NVIC reported 891 cases of intoxications through the use of food supplements in 2019. These adverse effects or intoxications may result in stomach complaints, headaches or dizziness, but also in more severe conditions such as hart complaints or even cerebral haemorrhage. It follows from inspection results of the Dutch Food Safety Authority NVWA that only 45 % of the food business operators comply with all applicable food safety requirements. Due to the lack of regulatory harmonisation in this field and the open norm laid down in the General Food Law Regulation (article 14 thereof states “food shall not be placed on the market if it is unsafe”), this makes effective enforcement of food safety for food supplement a complex task.

Dutch initiatives aimed at more EU harmonization for food supplements

In an ideal world, dangerous substances are prohibited on an EU-wide basis. Currently, an initiative is ongoing to add substances to the list of unsafe substances under the Fortification Directive. Furthermore, in February 2020, an initiative was launched by the enforcement authorities of 18 Member States including those of the Netherlands, to draft a joint list of prohibited substances for food supplements. Since both initiatives are not expected to materialize overnight, the Dutch Health Minister has decided, in cooperation with the Dutch Food Safety Authority and the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board CBG amongst others, to draft a national list of unsafe substances. This list will be based on risk evaluations pertaining thereto and the aim is to give this list a statutory basis, by integrating it in the Dutch Commodities Act (“Warenwet”). Furthermore, the Dutch Food Safety Authority has designed a targeted approach of sales of food supplements via the internet. Based on the Dutch polder tradition, this approach is consensus-based, aiming to agree with online marketplaces that they remove from their offerings any food supplements containing prohibited substances. Also, the Dutch Health Minister oversees that the communications to consumers on food supplements by a number of channels, such as the Netherlands Nutrition Centre (“Voedingscentrum”), the Health Inspectorate IGJ and the National Institute for Public Health RIVM, provides proper risk information. Finally, the Health Minister considers introducing a system of prior notification and some level of safety evaluation into the Netherlands as well.

Are these initiatives a good thing or a bad thing?

In order to enhance consumer safety, the above initiatives are certainly a good thing. For food business operators however, they may entail further obstacles to the free circulation of goods in the internal market. Based on the new Official Controls Regulation, enforcement authorities are allowed to do “mystery shopping”, i.e. ordering food supplements without identifying themselves. Once the Dutch national list of dangerous substances will have a statutory basis, the Dutch Food Safety Authority could do online test purchases with EU food business operators that may not be aware of such list. If their products are not in line therewith, they are subject to enforcement measures. As to the intended introduction of the notification requirement of food supplements in the Dutch market, this will certainly make market access less smooth.

On the other hand, in a number of EU countries, such as Belgium and France, a system of prior notification for food supplements is already in place. In practice, we see this can operate as a “safety seal”, meaning that supplements that were allowed on those markets, potentially earn more easily market access in other Member States as well. Furthermore, a new tool is available to food business operators since the new Regulation on mutual recognition became applicable in April 2020. Article 4 thereof offers the possibility to draw up a voluntary declaration to demonstrate to the competent authorities of other Member States that a food product is lawfully marketed, for instance in the Netherlands. The competent authorities in the Member State of destination can only oppose the further marketing thereof based on legitimate public interest, for instance public health. I expect this to be as useful tool for the further circulation of food supplements in the internal market.

Finally, I expect the Dutch national list of unsafe and hence prohibited substances for food supplements also to provide some more clarity in this field, provided that it will also be easily accessible to food business operators abroad. When these food business operators indeed duly inform themselves, this list could facilitate the successful EU-wide launch of food supplements, with less unclarity pre-launch and less surprises after launch. Which is supposed to be a good thing.

The information shared in this blogpost stems from a letter of the Dutch Health Minister to the Dutch House of representatives dated 14 December 2020, which can be viewed here (in Dutch only).

Posted: October 2, 2020 | Author: Jasmin Buijs | Filed under: Authors, cannabidiol, cannabis, Disclosure of information, Enforcement, Food, Food Supplements, Health claims |

Since 1 September 2020, the Dutch Food Safety Authority (NVWA) has been given the power to publish certain inspection results (including identification details of the inspected FBO) faster than before. Prior to that date, the legal basis for disclosure could primarily be found in article 8 of the Dutch Freedom of Information Act (in Dutch: Wet openbaarheid van bestuur). This act creates a duty for the administrative body concerned, for example the NVWA, to publicly provide information when this is in the interest of good and democratic governance. However, article 10 of the Freedom of Information Act requires an individual balancing of interests in order to avoid disproportionate disadvantage for the parties involved as a result of the publication. It also prohibits disclosure of certain sensitive information, such as company and manufacturing data that has been confidentially communicated to the government. This blog post explains what has changed since 1 September 2020, which FBOs are affected and what arguments they can use to prevent disclosure.

Since 1 September 2020, the Dutch Food Safety Authority (NVWA) has been given the power to publish certain inspection results (including identification details of the inspected FBO) faster than before. Prior to that date, the legal basis for disclosure could primarily be found in article 8 of the Dutch Freedom of Information Act (in Dutch: Wet openbaarheid van bestuur). This act creates a duty for the administrative body concerned, for example the NVWA, to publicly provide information when this is in the interest of good and democratic governance. However, article 10 of the Freedom of Information Act requires an individual balancing of interests in order to avoid disproportionate disadvantage for the parties involved as a result of the publication. It also prohibits disclosure of certain sensitive information, such as company and manufacturing data that has been confidentially communicated to the government. This blog post explains what has changed since 1 September 2020, which FBOs are affected and what arguments they can use to prevent disclosure.

Additional basis of disclosure as of 1 September 2020

As of 1 September 2020, the NVWA is additionally bound by the Decree on the Disclosure of Supervision and Implementation Data under the Health and Youth Act (in Dutch: Besluit openbaarmaking toezicht- en uitvoeringsgegevens Gezondheidswet en Jeugdwet, hereinafter: Decree on Disclosure), as further elaborated in the Policy Rule on Active Disclosure of Inspection Data by the NVWA (in Dutch: Beleidsregel omtrent actieve openbaarmaking van inspectiegegevens door de NVWA, hereinafter: Policy Rule on Disclosure). This power of disclosure is based on article 44 of the Dutch Health Act (in Dutch: Gezondheidswet). Disclosure in accordance with the Decree on Disclosure does not require the balancing of interests: disclosure of information will simply take place when indicated in the relevant annex to the Decree on Disclosure. Companies that wish to prevent publication of information related to their business will therefore have to invoke factual criteria, such as that the information to be disclosed contains incorrect information or concerns information that is excluded from disclosure in Article 44(5) of the Health Act.

Required actions when companies disagree with disclosure

The publication of information as based on the Decree on Disclosure has consequences for the way affected companies can stand up to prevent disclosure and the speed with which they will need to object. Where the Freedom of Information Act offers affected companies the possibility to share their opinion (in Dutch: zienswijze) in reaction to the administrative body’s intention to disclose the information in question, this possibility does not exist under the Decree on Disclosure. If and when an affected company does not agree with disclosure on the basis of the latter decree, this company has two weeks to object to the respective administrative body’s intention of disclosure and needs to seek interim relief measures within this time frame in order to actually suspend the disclosure. In addition, under the Decree on Disclosure companies are provided the option to write a short response that will be published together with the information subject to disclosure. In this way, affected companies are given the opportunity to provide the outside world with a substantive (but very summary) response to the information to be made public. The Policy Rule on Disclosure in fact also grants this right of response to information disclosed by the NVWA under the Freedom of Information Act.

Relevant for all FBOs?

The aforementioned additional legal basis for disclosure by the NVWA applies for the time being to a limited number of supervisory areas only, namely the inspection results of the NVWA with regard to (i) fish auctions, (ii) the catering industry, and (iii) project-based studies into the safety of goods other than food and beverages. These areas may be expanded in the future, according to the explanatory notes to the Decree on Disclosure.

However, for companies with so-called borderline products that navigate between different regulatory regimes, it is relevant to know that Dutch Health and Youth Care Inspectorate (IGJ) has broader powers to actively disclose inspection results under the Decree on Disclosure. Since 1 February 2019, the IGJ has already been publishing information on the basis of this decree regarding, amongst other, compliance with the Dutch Medicines Act (in Dutch: Geneesmiddelenwet). This means that when the IGJ takes enforcement measures against a FBO handling food supplements or other foodstuffs that qualify as (unregistered) medicines, it may be obliged to make public the respective supervisory information. The same applies to enforcement under the Dutch Medical Devices Act (in Dutch: Wet op de medische hulpmiddelen) – think diet preparations – and the Opium Act (in Dutch: Opiumwet) – think CBD and other cannabis products.

However, for companies with so-called borderline products that navigate between different regulatory regimes, it is relevant to know that Dutch Health and Youth Care Inspectorate (IGJ) has broader powers to actively disclose inspection results under the Decree on Disclosure. Since 1 February 2019, the IGJ has already been publishing information on the basis of this decree regarding, amongst other, compliance with the Dutch Medicines Act (in Dutch: Geneesmiddelenwet). This means that when the IGJ takes enforcement measures against a FBO handling food supplements or other foodstuffs that qualify as (unregistered) medicines, it may be obliged to make public the respective supervisory information. The same applies to enforcement under the Dutch Medical Devices Act (in Dutch: Wet op de medische hulpmiddelen) – think diet preparations – and the Opium Act (in Dutch: Opiumwet) – think CBD and other cannabis products.

An example: melatonin-containing foodstuff labeled as a medicine

An example: melatonin-containing foodstuff labeled as a medicine

An example of a FBO that was faced with disclosure in accordance with the Decree on Disclosure by the IGJ concerns a company involved in melatonin-containing products. The IGJ intended to publish an inspection report on these products, from which it would follow that the products in question qualify as medicines and that the FBO concerned would therefore illegally place them on the market (namely without the required licenses under the Medicines Act). The FBO at stake applied for a preliminary injunction suspending the publication decree. On 8 July 2020, the preliminary relief judge rendered a judgment in this case.

Possible factual criteria to prevent naming & shaming

Although disclosure under the Decree on Disclosure is obligatory and disclosure decisions thus do not require the balancing of interests, the above-mentioned melatonin case gives good insights into the factual criteria that can nevertheless be invoked to prevent disclosure. In this case, the respective FBO brought forward the following arguments.

The respective inspection report excluded from disclosure

Article 3.1(a) of Part II of the Annex to the Decree on Disclosure excludes certain supervisory information from disclosure, including the results of inspections and investigations established as a result of a notification by a third party. The FBO at stake (hereinafter: “Applicant’) takes the position that the present inspection report was initiated as a result of a notification or enforcement request by a competitor. This would mean that the respective inspection report must not be made public.

The preliminary relief judge cannot agree with this position in the present case and rules that the inspection report is clearly related to an earlier letter from the IGJ to the applicant in which it announced the intensification of supervision of melatonin-containing products. Moreover, the case file was silent on a notification or enforcement request by a competitor.

The preliminary relief judge additionally states that it agrees with the IGJ’s viewpoint that the inspection report does not concern a penalty report (the report was drafted within the context of supervision and only indicates that Applicant will be informed about the to be imposed enforcement measure by separate notice). The fact that Applicant had earlier received a written warning for violation of the Medicines Act has no influence on this. The inspection report is therefore neither excluded from publication pursuant to article 3.1(a)(ii) of Part II of the Annex to the Decree on Disclosure, which makes an exception for “results of inspections and investigations that form the basis of decisions to impose an administrative fine”.

Disclosure in violation of the goal of the Health Law: outdated scientific foundation conclusions IGJ

The purpose of disclosure under the Health Act, in the wording of article 44(1) of that act, is to promote compliance with the regulations, to provide the public with insight into the way in which supervision and implementation of the Decree on Disclosure is carried out and into the results of those operations. Pursuant to Article 44a(9) of the Health Act, information should not be made public where this is or may violate aforementioned purpose of disclosure. Applicant takes the position that publication of the present inspection report does not contribute to improved protection of the public or to better information about the effects of melatonin, as a result of which the report should not be disclosed. More specifically, the applicant complains that the report (i) contains obvious errors and inaccuracies, (ii) gives the impression that it concerns a penalty decision, and (iii) is based on an incorrectly used framework to determine whether the qualification of a medicine is met.

The preliminary relief judge first of all notes that the fact that Applicant does not agree with the conclusions of the inspection report does not mean that the report therefore contains obvious inaccuracies. The preliminary relief judge further summarizes Applicant’s position as follows: (i) the IGJ wrongly took a daily dosage of 0.3 mg melatonin to determine the borderline between foodstuff and medicines; (ii) in doing so, the IGJ did not demonstrate that products with a daily dose of 0.3 mg melatonin actually acts as a medicine; (iii) moreover, the product reviews refer to outdated scientific publications (a more recent study by one of the authors thereof as well as more recent EFSA reports have not been included in the inspection report), whereas the current state of scientific knowledge must be taken into account according to established case-law. For these reasons, the preliminary relief judge agreed with Applicant that the IGJ has not made it sufficiently clear that from a daily dose of melatonin of 0.3 mg or more a ‘significant and beneficial effect on various physiological functions of the body’ occurs scientifically – according to the current state of scientific knowledge – and that products with a daily dose of melatonin of 0.3 mg or more act as a medicine”. Having said that, the preliminary relief judge did not accept Applicant’s statement that disclosure is contrary to the purpose of disclosure under the Health Act. Instead, the preliminary relief judge sought to comply with the so-called principles of sounds administration (in Dutch: algemene beginselen van behoorlijk bestuur) and ruled that the disclosure decision was not diligently prepared and insufficiently substantiated.

Incorrect facts

Applicant claims that the inspection report contains various inaccuracies, including the incorrect information that Applicant would produce melatonin itself. Applicant had already raised these inaccuracies in her response to the draft version of the report, but this had not resulted into adjustments in the final, to be published version of the report. The preliminary relief judge ruled on this matter that the IGJ should further investigate Applicant’s concerns and should amend the report where relevant. After all, the content of the report must be correct and diligently compiled. The mere fact that Applicant was given the opportunity to respond to the draft version of the report and that the IGJ responded to this in its decision to disclose the report does not mean that this requirement is met.

Violation of article 8 ECHR: disclosure has a major impact on Applicant’s image

Applicant claims that the planned disclosure will have a major impact on Applicant’s image and that of the natural person involved in the company. This is in violation of article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) concerning the right to respect for private and family life. The Explanatory Memorandum to the Amendment to the Health and the Youth Care Act (in Dutch: Memorie van Toelichting op de Wijziging van de Gezondheidswet en de Wet op de Jeugdzorg) deals with this in detail. It emphasizes that the disclosure of inspection data does normally not constitute an interference with private life, because the data normally relates to legal persons and not to natural persons. The aforementioned Explanatory Memorandum therefore concludes that article 8 ECHR does not preclude disclosure on the grounds of the Health Act. Nevertheless, the court has at all times the competence to review a disclosure decision in the light of that article, in which case it will in fact have to balance the interests involved. In the present case, preliminary relief judge sees however no reason to assume a violation of article 8 ECHR.

Although the above shows that the preliminary relief judge in the respective melatonin case does not agree with all arguments put forward by Applicant, the request for suspension of publication of the contested inspection report was nevertheless granted thanks to factual criteria that were sufficiently substantiated. In particular the (implicit) argument that the conclusions in the inspection report lack a sufficient factual basis affects the essence of the information to be disclosed.

Conclusion

Rapid action is required to prevent active disclosure of inspection results under the Decree on Disclosure as these will usually be published after two weeks. This is not only relevant for FBOs active in the supervisory areas of the NVWA as designated in the Decree on Disclosure, but also for FBOs that operate at the interface of legal regimes under the supervision of the IGJ. To suspend disclosure, interim relief proceedings will have to be instituted as the Decree on Disclosure no longer provides for the possibility of submitting an opinion prior to publication. Moreover, affected companies cannot invoke the argument of suffering a disproportionate disadvantage as a result of the publication. Publication on the basis of the Decree on Disclosure is namely not subject to an individual balancing of interests (apart from an assessment on the basis of article 8 ECHR, insofar relevant). Although the arguments that companies can bring forward to prevent publication are therefore more limited than in the case of disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act, this does not mean that companies cannot successfully object an intention of disclosure. The melatonin case mentioned above is an example of this: conclusions that are not based on most recent science may not be published without adequate justification. Also, facts that are alleged to be incorrect should be further investigated before disclosure.

Posted: August 24, 2018 | Author: Jasmin Buijs | Filed under: Authors, Food, Food Supplements, Health claims, Information |

Probiotics are known as “beneficial bacteria” that can be found in, amongst others, dairy products and food supplements. They are defined by the joint FAO/WHO expert consultation on probiotics as “live microorganisms that, when administrated in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host”. Since the reference to probiotics implies a health benefit, it comes as no surprise that the statement “contains probiotics” in a commercial communication about a food product constitutes a health claim under the Claims Regulation. Moreover, “contains probiotics”, or “prebiotics”, is explicitly taken as an example of a health claim in the guidance on the implementation of Regulation 1924/2006 of the European Commission’s Standing Committee on the Food Chain and Animal Health. At this moment, no health claims for probiotics have been approved by the European Commission. The Dutch Research institute TNO and the world’s first microbe museum Micropia, located in Amsterdam, are nevertheless convinced of the health benefits of probiotics, in particular to protect against antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD). At the beginning of this month, they launched a so-called National Guide on clinically proven probiotics for use during antibiotic treatment in the scientific journal BMC Gastroenterology

Probiotics are known as “beneficial bacteria” that can be found in, amongst others, dairy products and food supplements. They are defined by the joint FAO/WHO expert consultation on probiotics as “live microorganisms that, when administrated in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host”. Since the reference to probiotics implies a health benefit, it comes as no surprise that the statement “contains probiotics” in a commercial communication about a food product constitutes a health claim under the Claims Regulation. Moreover, “contains probiotics”, or “prebiotics”, is explicitly taken as an example of a health claim in the guidance on the implementation of Regulation 1924/2006 of the European Commission’s Standing Committee on the Food Chain and Animal Health. At this moment, no health claims for probiotics have been approved by the European Commission. The Dutch Research institute TNO and the world’s first microbe museum Micropia, located in Amsterdam, are nevertheless convinced of the health benefits of probiotics, in particular to protect against antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD). At the beginning of this month, they launched a so-called National Guide on clinically proven probiotics for use during antibiotic treatment in the scientific journal BMC Gastroenterology

National Guide

The National Guide is presented as a tool for healthcare professionals, patients and other consumers to recommend or use the probiotic products listed as scientifically proven to prevent diarrhea caused by the use of antibiotics. While antibiotics fight bacterial pathogens, they also have a disruptive effect on the body’s own gut bacteria. One in four adults experiences diarrhea caused by ADD. The National Guide promotes probiotics for their function of protecting the gut flora from the disruptive effects of antibiotic treatment, fostering recovery and reducing the risk of recurring infections.

Science-based approach

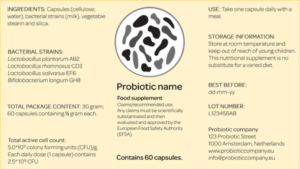

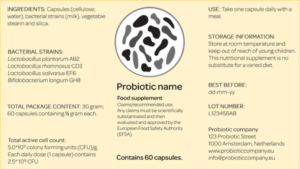

The research behind the Guide involves a literature study of clinical studies that are all based on randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled trials. Moreover, all of the trials clearly define AAD and have a probiotic administration regime for a period no shorter than the antibiotic therapy. 32 of the 128 initially identified clinical studies were selected in line with the aforementioned criteria. After the selection and review process, available probiotic products on the Dutch market were listed to be subsequently matched with the formulations as proven effective in the selected clinical studies. Only eight probiotic dairy products and food supplements marketed in the Netherlands specified on their label the respective probiotic strain(s) and number of colony-forming units (CFUs) and could therefore be used in the research. The listed probiotic products were awarded with one (lowest) to three (highest) stars for their proven effect as demonstrated in at least one to three clinical studies. The strain Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG with a minimal daily dose of 2 × 109 CFU was found in at least three clinical studies and therefore awarded with a three-star recommendation. This strain was found in 2 products, both of which are food supplements. Several multi-strain formulations resulted in a one-star recommendation; 5 food supplements and 1 dairy product matched such a formulation. The multi-strain formulation Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5 and Bifidobacterium lactis BB-12 was present in two clinical studies and therefore assigned with a two-star recommendation. However, none of the listed probiotic products found on the Dutch market contained this formulation.

Plea for the labeling of probiotics

Plea for the labeling of probiotics

The research is not exhaustive as probiotic products other than the eight that were included in the study might also be effective. However, since this was not communicated on the label, they could not be included in the research. To overcome this gap, TNO and Micropia as the initiators of the National Guide call for the labeling of the probiotic strains and number of CFUs on all probiotic products EU-wide. This could also expand the potential of the Guide. At this moment, strain and CFU labeling of probiotic products is not legally mandatory under the Food Information for Consumer Regulation. The initiators also developed a special probiotic label to address this claimed deficiency. The label is based on the probiotic label used in the US as created by the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP). The labels are in line with the information that should be demonstrated on probiotic labels according to the FAO/WHO 2002 Working Group on Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food.

National Guide to circumvent limitations under the Claims Regulation?

The Claims Regulation applies to health (and nutrition) claims made in commercial communications of foods to end consumers. This may be in the labeling, presentation or advertising of the food. Besides information on or about the product itself, also general advertising and promotional campaigns such as those supported in whole or in part by public authorities fall within the scope of the Regulation. Moreover, since the Innova Vital case, we know that (science-based) communications made to healthcare professionals may also be regulated by the Claims regulation. The rationale thereof is that the healthcare professional can promote or recommend the food product at issue by passing the information on to the patient as end consumer. Only non-commercial communications, such as publications that are shared in a purely scientific context, are excluded from the Regulation.

It must be noted that the National Guide is, unlike health claims, not a commercial communication originating from food business operators. This does, however, not necessarily mean that food business operators are free to use the science-based Guide in their communication with (potential) consumers or even with healthcare professionals without any reservation. The Guide, which not only lists the probiotic formulations that are beneficial for the human gut flora, but even the names of products that contain those formulations, could turn commercial when referred to by a food business. Moreover, when shared in such a context, the claims made in the National Guide may even enter the medical domain due to the preventive function assigned to foods containing probiotics.

Conclusion

The history of probiotic health claim applications has shown that EFSA is not easily convinced of the evidence that is correspondingly provided. The National Guide is, however, not subject to approval from the European Commission, backed by a positive opinion from EFSA. The Guide’s publication in the peer-reviewed journal BMC Gastroenterology nevertheless contributes to the verification of its scientific substantiation. The Guide therefore appears as an innovative, science-based alternative for probiotic health claims. At the same time, food business operators should be careful in referring to the National Guide to not act beyond the borders of the Claims Regulation and to stay away from medical claims. As a very minimum however, it seems to be valuable work to be adopted by branch organizations or research exchange platforms, such as the International Probiotics Association.

Posted: December 13, 2017 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Food, Food Supplements, Health claims, Information |

Consumers across all demographics are increasingly concerned about cognitive health and performance. For that reason, Food Matters Live, held in London from 21 – 23 November last, dedicated one of its Seminars to the exploration of new R&D advancing the understanding of nutrition and cognitive health and performance. I was asked to give a presentation on meeting standards for cognitive claims, of which you will find a summary below. You will note that in addition to the system of currently authorised claims, I will explore its flexibility, as well as the options outside its scope.

Consumers across all demographics are increasingly concerned about cognitive health and performance. For that reason, Food Matters Live, held in London from 21 – 23 November last, dedicated one of its Seminars to the exploration of new R&D advancing the understanding of nutrition and cognitive health and performance. I was asked to give a presentation on meeting standards for cognitive claims, of which you will find a summary below. You will note that in addition to the system of currently authorised claims, I will explore its flexibility, as well as the options outside its scope.

FIC Regulation

The general framework for health claims is contained both in the FIC Regulation and in the Claims Regulation. The FIC Regulation embodies the principle of fair information practises. According to this principle food information should not be misleading as to the characteristics of the food, for example by attributing it effects it does not possess. Furthermore, the FIC Regulation prohibits any medical claims to be made in connection with food products. A medical claim is to be understood as any claim targeting the prevention or treatment of a particular disease. It is for instance not permitted to state that a food supplement alleviates the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis.

Claims Regulation

The Claims Regulation lays down the very concept of a health claim, being a voluntary message in any form that states or suggests that a food has particular characteristics. Basically, a health claims conveys the message “What does the product do?” Health claims can only be made with regard to a particular nutrient that has been shown to have a beneficial nutritional of physiological effect. Such nutrient should be present in the end product in a form that is bio available and to such extent that it produces the claimed effect. The scope of the Claims Regulation includes all commercial communications regarding food products to be delivered to the final consumer. Based on the Innova / Vital decision of the ECJ, it was clarified that such final consumer can also be a health care professional.

Legal framework for cognitive claims

Currently, authorised claims for cognition can be linked to iodine, iron and zinc. For all of these compounds, the claim “contributes to the normal cognitive function” can be made. In addition, for iodine the claim “contributes to the normal functioning of the nervous system” is available and for iron a claim specifically targeting children can be made. The conditions of use for these claims are calculated on the reference intake (“RI”) applicable to each mineral. As such, a distinction is being made between solids (15 % RI) and fluids (7.5% RI). For instance, in order to allow a cognition claim linked to iron, the end product should at least contain 2.1 mg iron / 100 g or 1.05 mg / 100 ml. Any claim should refer to a food product ready for consumption, prepared in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Flexibility in wording

In practise, I see that many food business operators try to reword the authorised claims, as they are not considered to be a major add-on. In the Netherlands, this practise has been facilitated by the Council for the Public Advertising of Health Products (Keuringsraad KOAG-KAG), who has published a list of alternative, authorized claims. For instance, for a claim on zinc, the Dutch translation of the wording “contributes to a regular problem-solving ability” is permitted as an alternative. Regarding a claim on iodine, you could think of “plays an important role in mental activity.” Furthermore, it is also permitted to state that a food product containing the required minimum of iron “contributes to regular intelligence”. Now we are talking!

Examples found in practise

An internet search for products targeting cognition revealed that many of them are not linked to the EU authorized claims at all. For instance, the company Flora Health is marketing the food supplement ginkgo biloba, claiming that it “helps to enhance cognitive function and memory in an aging population.” Also, the food supplement Mind Focus containing various vitamins, minerals and green tea extract from the company Bio Fusion was found, which allegedly “improves mind focus and concentration instantly”. Furthermore, the green oat product Neuravena was found, regarding which five clinical studies confirm it benefits to cognitive function. How can this be explained? The first two examples contain claims that in the EU would no doubt qualify as medical claims and as such are prohibited.

Non-EU products and options outside cognitive claims framework

Products that do not comply with EU standards may originate from other countries or territories that are subject to a different regulatory regime than applicable in the EU. Without endorsing any claims made, it was found that the gingko and Mind Focus products originated from Canada and the US respectively. The same is not true for the product Neuravena, as its manufacturer Frutarom claims to be a “global manufacturer of health ingredients backed by the science, and supported with documentation and the regulatory compliance our customers demand.” The difference here is that Neuravena is not advertised on a commercial setting targeting end consumers, but in a scientific portal. The website even contains a disclaimer to that extent. In a non-commercial, purely scientific environment, the Claims Regulation is not applicable. This allows FBO’s, provided that the same website does not contain a click through ordering portal, to communicate on their R&D and cognition even outside the authorised EU framework.

Conclusion

The EU authorised claims for cognition are limited in number and scope. Several EU Member States offer considerable flexibility in wording, which makes the use of claims much more appealing. Furthermore, in a science-based context, the Claims Regulation is not applicable, which allows you plenty of opportunity to communicate your latest R&D on nutrition & cognition, provided that the message is strictly scientific and not commercial.

Posted: July 12, 2017 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Food, Food Supplements, Health claims, novel food | Tags: botanical, market access, medicinal, novel food |

The People’s Republic of China first law on Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicine came into force on the 1st of July 2017. This law encompasses industrial normalization by guaranteeing the quality and safety of herbs in cultivation, collection, storage and processing. Producers of Traditional Chinese Medicine (hereinafter TCM) are not only targeting the Chinese market, but are also looking for access to the European market. With this new legislation in force in China, it is a good time to have a look at the current possibilities for market access of TCM on the European market. The name “TCM” would suggest the product could only be qualified as a medicinal product. However, other product qualifications are possible as well. In this post, it will be investigated how Chinese herbal remedies and products fit into the EU framework.

The People’s Republic of China first law on Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicine came into force on the 1st of July 2017. This law encompasses industrial normalization by guaranteeing the quality and safety of herbs in cultivation, collection, storage and processing. Producers of Traditional Chinese Medicine (hereinafter TCM) are not only targeting the Chinese market, but are also looking for access to the European market. With this new legislation in force in China, it is a good time to have a look at the current possibilities for market access of TCM on the European market. The name “TCM” would suggest the product could only be qualified as a medicinal product. However, other product qualifications are possible as well. In this post, it will be investigated how Chinese herbal remedies and products fit into the EU framework.

Qualification

For market access, product qualification is vital. Qualification of TCM as medicinal products might seem obvious. However, western medicine is mostly focused on curing a certain disease or disorder, whereas TCM is focused on healing the body itself. Healing in short means the body should be strengthened to ‘treat itself’. Many of the traditional herbal remedies have healing properties, such as strengthening the immune system. As an alternative to medicinal products, other qualifications of TCM could be botanicals, so that they could be marketed as food supplements or as other foodstuffs. We previously reported on product qualification in this blog, explaining what legal tools have been developed for this purpose over time in case law. These criteria equally apply to TCM.

Simplified registration procedure for traditional herbal medicinal products

An example of a traditional herbal medicinal product we can mention sweet fennel, which is indicated for symptomatic treatment of mild, spasmodic gastro-intestinal complaints including bloating and flatulence. For this group of traditional herbal medicinal products, just like for TCM, a simplified registration regime can be found in the EU Medicinal Products Regulation. In short, the efficacy of the product containing the herb used in TCM’s can be substantiated with data on usage of the herb. This eliminates the need for costly clinical trails to prove the efficacy of the active ingredient(s) in the product. However, safety and quality of the TCM still need to be substantiated.

Eligibility for simplified registration procedure

To qualify as traditional herbal medicinal product, a number of cumulative criteria should be met, including the following.

- Evidence is available on medicinal use of the product during at least 30 years prior to application for EU market authorization, of which at least 15 years within the EU.

- Such evidence sufficiently demonstrates the product is not harmful in the specified conditions of use and the efficacy is plausible on the basis of longstanding use and experience.

- The product is intended and designed for use without the supervision of a medical practitioner and can only be administrated orally, externally and/or via inhalation.

The presence in the herbal medicinal product of vitamins or minerals for the safety of which there is well-documented evidence shall not prevent the product from being eligible for the simplified registration referred to above. At least, this is the case as the action of the vitamins or minerals is ancillary to that of the herbal active ingredients regarding the specified claimed indication(s). TCM intended and designed to be prescribed by a medical practitioner can enter the EU market, but cannot benefit from the simplified registration procedure for traditional herbal medicinal products.

Foodstuff

Currently the focus of healthcare is shifting from purely curing diseases to prevention thereof. TCM could play an interesting role in such paradigm shift. Although food business operators (hereinafter FBOs) cannot claim a foodstuff can cure a disease, such product can contribute to prevention of a disease. As such, FBOs can inform the public that consumption of a particular foodstuff can support the regular action of particular body functions. An example of a herbal remedy used in TCM and currently on the EU market is cinnamon tea; used in Chinese medicine to prevent and treat the common cold and upper-respiratory congestion. Obviously, the advantage of bringing a foodstuff (for instance, a food supplement) to the market as opposed to a medicinal product is that unless the foodstuff is a Novel Food, you do not need a prior authorization.

Novel Foods

As long as a foodstuff has a history of safe use in the EU dating back prior to 1997, FBOs do not need prior approval for market introduction. If no such history of safe use can be established, both the current and new Novel Food Regulation prescribe that the FBO receives a Novel food authorization. A helpful tool for establishing a history of safe use is the novel foods catalogue, being a non-exhaustive list of products and ingredients and their regulatory status. Another source is Tea Herbal and infusions Europe (hereinafter THIE); the European association representing the interests of manufactures and traders of tea and herbal infusions as well as extracts thereof in the EU. THIE’s Compendium, which should be read in combination with THIE’s inventory list (also non-exhaustive), contains numerous herbs and aqueous extracts thereof, which are used in the EU. Other herbs might not be considered Novel Foods, as long as the FBO can prove a history of safe use in the EU prior to 1997. For instance, the history of safe use of Goji berries has been successfully substantiated.

Traditional foodstuffs from third countries

In previous blogs we already pointed to a new procedure to receive a Novel Food authorization as of 1 January 2018, relating to ‘traditional foods from third countries’. EFSA published a guidance document for FBOs wishing to bring traditional foods to the EU market, enabling them to use data from third counties instead of European data for the substantiation of the safety of the foodstuff. The procedure is a simplified procedure to obtain a Novel Food authorization for a foodstuff, which has been consumed in a third country for at least a period of 25 years. For sure, this is not an easy one, but we have high hopes that such data can be established for TCM being used in Asia. In the affirmative, the FBO can use these data to substantiate the safety of the product and receive a Novel Foods authorization via a 4 months short track procedure, enabling the FBO to market the foodstuff at stake in the EU.

Health claims for herbal products

The EU Claims Regulation provides the legal framework for health and nutrition claims to be used on foodstuffs. In previous blogs we elaborated how such claims can be used for botanicals, being herbs and extracts thereof. So far, no authorized claims for botanicals are available, but their use is nevertheless possible under certain circumstances. In sum, an on-hold claim can be used when the FBO clearly states the conditional character thereof (by stating the number of such on hold claim on this claims spreadsheet. Upon dispute, the FBO should furthermore be able to substantiate that the compound in the final product can have the claimed effect when consumed in reasonable amounts. TCM can take advantage of this current practice, thereby communicating the healing effect thereof, which basically comes down to a contribution to general health. It should be carefully checked though, if the claim for the herbal remedy at stake has not been rejected, as happened to four claims regarding caffeine.

Conclusion

EU market introduction of TCM could take place in various ways, depending on the qualification of the product at stake. Qualification as a regular foodstuff certainly ensures the quickest way to market, as no prior market approval is required. This will be different if the product qualifies as a Novel Food. However, as of 1 January 2018, a fast track authorization procedure will be available for traditional foods from third countries, from which TCM might benefit as well. TCM could furthermore use so-called botanical claims, in order to communicate the healing effects thereof. When the TCM qualifies as a medicinal product, the good news is that for traditional herbal medicinal products, a simplified registration procedure is available under the EU Medicinal Product Directive, provided that certain criteria are met. Registration takes place via the national competent authorities in each Member State, which in the Netherlands is the Medicines Evaluation Board (CBG).

Posted: October 14, 2016 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Enforcement, Food Supplements |

Photo Peter Hilz / HH

As observed in an earlier post, the boundaries between food products and medicinal products are sometimes blurred. However, the qualification of a product as either one or the other may have huge regulatory consequences. In recent litigation in several Dutch Courts the Hecht-Pharma decision from the EU Court of Justice (ECJ) was applied. This series of cases is of interest for food business operators, as it provides a clear message regarding enforcement measures directed against borderline products. The national health authorities should strike a fair balance between the free movement of goods and the optimal protection of public health. Whereas enforcement policies re. borderline products constituting a threat to public health may be justified, this does not entail that each and every food product containing a substance with a physiological effect automatically qualifies as a medicinal product by function.

Red Rice

The facts of the case Hecht-Pharma related to a food supplement with fermented rice that Hecht-Pharma had been marketing in Germany under the name “Red Rice”. The recommendations for use read “as food supplement, 1 capsule, 1 – 3 times a day”. The German authorities had qualified this product as a medicinal product by function, but Hecht-Pharma did not agree. It argued that having regard to the recommended dose, the product at stake could not exert a pharmacological action.

Medicinal product by function

In its request for a preliminary ruling, the Federal Administrative Court aimed to clarify if, after a change of the Medicinal Products Directive, criteria previously developed to establish if a product qualified as a medicinal product by function, still applied. Qualification as a product as a medicinal product by function implies that it is aimed at a change in physiological functions by exerting a pharmacological, immunological or metabolic action. The ECJ confirmed in its Hecht-Pharma decision that previously developed criteria were still in place. As a result, the national authorities must decide on a case-by-case basis, taking into account all the characteristics of the product at stake, in particular its composition and pharmacological properties, the manner in which it is used, the extent of its distribution, its familiarity to consumers and the risks which its use may entail when they decide if a product qualifies as a medicinal product by function. Clearly, a product cannot be regarded as such, when it is incapable of appreciably restoring, correcting or modifying physiological functions in human beings.

Melatonin-based products

The Dutch Court cases related to melatonin-based products, marketed by a number of companies represented by the Dutch foods supplements association NPN (Natuur- en Gezondheidsproducten Nederland). During the period between 2011 and 2014, The Dutch Health Inspectorate (IGZ) and the Dutch Food Safety Authority (NVWA) on the one hand and NPN on the other hand, corresponded on the topic of melatonin-based products. The Dutch authorities thereby took the view that they considered products containing 0,3 mg melatonin or more to be a medicinal product by function. They based their view on literature studies, from which it would follow that a single oral dose of 0,3 mg melatonin produced a pharmacological effect on humans. In view of their public role of safeguarding public health, the authorities intended to launch enforcement measures regarding products containing more than 0,3 mg melatonin, unless the manufacturer at stake had applied for an authorization to market these products as medicinal products.

Enforcement measures and subsequent summary proceedings

Early 2015, IGZ sent a letter to all Dutch manufacturers of melatonin-based products informing that they would require a market authorization for continued marketing of products containing 0.3 mg melatonin or more. Each such manufacturer should inform the authorities prior to 15 March 2015 for which melatonin-based products it would or it had already applied for such authorization, failing which enforcement measures could follow. NGN subsequently initiated summary relief proceedings, claiming inter alia that IGZ should refrain from enforcement measures, unless it had demonstrated with respect to each and every melatonin-based product that it qualified as a medicinal product according to applicable legal criteria as validated in case law. In these proceedings, NPN claimed that IGZ had not sufficiently demonstrated, based on scientific evidence, that products containing 0,3 mg melatonin or more could change physiological functions in the human body, for instance by a pharmacological effect. Furthermore NGN argued that IGZ had neglected to apply the criteria developed in Hecht-Pharma, according to which IGZ should have established with respect to each melatonin-based product that it qualified as a medicinal product, thereby taking into account all relevant circumstances. According to NPN, these products were food supplements, not medicinal products.

Evaluation by the Court in summary proceedings

Based on a very broad interpretation of the definition of medicinal product, as contained in article 1.2 of the Medicinal Products Directive, NGN’s claim was dismissed. According to the Court, assessment of each individual product could be done by the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board or by EMA, upon filing of an application for marketing authorization. It was not necessary for IGZ to proceed to this evaluation at an earlier stage, as the chances that any deviations from the general conclusion would be found, were considered very small. The Court did consider however that IGZ’s communication and application of enforcement measures had not been unambiguous. Even if the manufacturers of the melatonin-based products followed the request to indicate by 15 March 2015 for which products they filed an application for marketing authorization, it would not be clear by when they would know if IGZ – pending such application – would refrain from enforcement measures. This created uncertainty in the market and was considered unlawful vis-à-vis NGN. The Court therefore ordered IGZ to set a term after 15 March 2015 during which the products for which a market authorization had been requested would be tolerated.

Decision reversed on appeal in summary proceedings

On appeal, the discussion was focused on the correct application of Hecht-Pharma. Contrary to the Court in first instance, the Appeal Court held that a public health authority announcing enforcement measures should at that very moment motivate why a product containing > 0,3 mg melatonin qualifies as a medicinal product. A different approach could create unjust market restrictions, for instance regarding products that upon application were not considered medicinal products. Moreover, the requirement to file a market authorization for each and any melatonin-based product containing > 0,3 mg melatonin is not just a formality, but would oblige manufacturers of this type of products to make an important investment in time and resources. Taking into account there were no acute health issues for the continued marketing of melatonin-based products, at least not for those containing a maximum up to 5 mg melatonin, the Appeal Court ordered that public health authorities should apply all criteria developed in Hecht-Pharma when considering enforcement measures against borderline products.

Confirmation in proceedings on the merits

This summer, the District Court of The Hague confirmed in a decision on the merits the appeal decision in summary proceedings discussed above. In short, this Court held that the unconditional qualification of a group of products as medicinal products, without any individual evaluation taking place, was not in line with EU case law. The Court in particular referred to paragraph 68 of the conclusion of the Advocate General. The Advocate General stated, inter alia, that the insidious extension of the scope of the Medicinal Product Directive by including products that do not belong there, would harm the free movement of goods. Therefore, until an individual assessment of a borderline product based on the Hecht-Pharma criteria has taken place, the public health authorities are not allowed to take any enforcement measures. No appeal was filed by IGZ against the present decision of The Hague District Court, but we were informed that where necessary, IGZ will proceed to enforcement in individual cases.

Take home

If and when your company receives a warning letter from IGZ announcing enforcement measures because of its borderline status, please bear in mind the following. Before considering any change in the product like the lowering of its active substance or even its withdrawal from the market, the public authorities should have unconditionally qualified the product at stake as a medicinal product. If and when this situation is not clear, make sure to obtain professional advice to properly deal with the health authorities.

Posted: August 15, 2016 | Author: Karin Verzijden | Filed under: Authors, Food, Food Supplements, Health claims, Information |

In the last post of last year, we reported on the use of health claims for food products directed at weight loss. In essence, the level playing field is pretty limited. The Claims Regulation does not allow using any claims that make reference to the rate or amount of weight loss. Under certain conditions, it is allowed to market a food product stating that its consumption will decrease the sense of hunger or increase the sense of satiety, but that’s about it. Early this summer, the Dutch Advertising Code Committee (Reclame Code Commissie, “RCC”) ruled in a case relating to weight loss, but considered the claims made therein were not inappropriate. What was the background of this case and what type of product was involved? All those who are interested in advertising products targeting weight loss, keep on reading.

Self-regulation of Marketing Food Products in the Netherlands

The RCC is a self-regulatory body of the Dutch Advertising Code Authority, ruling on complaints that can be lodged by both companies and individuals. Rulings are made based on the Dutch Advertising Code and a number of satellite codes, such as The Advertising Code for Food Products and the Code for Advertising directed at Children and Young People. The RCC also bases its Rulings on the advertising provisions contained in the Dutch Civil Code, as well as on particular provisions from the Claims Regulation and the Food Information to Consumers Regulation. Although the RCC Rulings are not legally binding, there is a high degree of compliance (about 96%). This is explained by the fact that the Dutch Advertising Code Authority has been put in place by joint decision of the Dutch advertising companies, whom make a yearly contribution for its operation in proportion to their marketing budget.

Clearance and monitoring services