SUP Directive: Restrictions on plastic food packaging (and other plastic products)

Posted: August 25, 2021 | Author: Jasmin Buijs | Filed under: Authors, Food | Comments Off on SUP Directive: Restrictions on plastic food packaging (and other plastic products) Last month, the European Single Use Plastics (SUP) Directive came into force. The purpose of this Directive is to reduce plastic litter, especially in the sea. Think for example of styrofoam hamburger trays or disposable plastic salad boxes for a meal on the go. The SUP Directive is part of the European action plan towards a circular economy (part of the Green Deal), to which re-use and recycling of products is central. The SUP Directive includes a phased introduction of various measures, with the goal of all plastic packaging being reusable or easily recyclable by 2030.

Last month, the European Single Use Plastics (SUP) Directive came into force. The purpose of this Directive is to reduce plastic litter, especially in the sea. Think for example of styrofoam hamburger trays or disposable plastic salad boxes for a meal on the go. The SUP Directive is part of the European action plan towards a circular economy (part of the Green Deal), to which re-use and recycling of products is central. The SUP Directive includes a phased introduction of various measures, with the goal of all plastic packaging being reusable or easily recyclable by 2030.

Scope SUP Directive

The SUP Directive primarily covers single-use plastic products. This includes packaging and other products that are partially made of plastic, such as cardboard boxes with a plastic coating. Plastics are materials consisting of a polymer, to which additives may have been added. Natural polymers that occur naturally in the environment are excluded from the definition of ‘plastic’. Bio-based and biodegradable plastics (based on natural polymers that have been chemically modified) are instead covered under the Directive. Single-use refers to the situation in which the product is not conceived, designed or placed on the market to accomplish, within its life span, multiple trips or rotations by being returned to a producer for refill or re-sued for the same purpose for which it was conceived. What exactly constitutes a single-use plastic product is further clarified in a guideline issued by the European Commission. Among other things, the composition and potential washability and repairability of the product play a role in this.

In addition to single-use plastic products, the SUP Directive also pays attention to products made of oxo-degradable plastics and fishing gear. Fishing gear is namely responsible for a large percentage of the plastics in marine litter. Oxo-degradable plastics are addressed by the Directive because these plastics have a negative impact on the environment and do not fit within a circular economy. This is because oxo-degradable plastics fragment into tiny particles, which then disappear in the environment.

Restrictions on placing on the market

Since 3 July 2021, the date of application of the SUP Directive, it has been prohibited to market products made of oxo-degradable plastics and the plastic products listed in Part B of the Annex to the SUP Directive. This includes plates, beverage stirrers, certain food containers as well as cups and containers for beverages made of expanded polystyrene (a type of styrofoam), sticks to be attached to and to support balloons, including the mechanisms of such sticks (unless for professional applications) and cotton bud sticks and straws (unless they qualify as medical devices).

The trade ban applies to the above-mentioned packaging and other plastic products placed on the market from 3 July 2021. The term ‘placing on the market’ refers to a product being supplied for distribution, consumption or use on the market of a Member State in the course of a commercial activity, whether in return for payment or free of charge, for the first time. Plastic products that have already become part of the supply chain in a given Member State before the trade ban entered into force, for example because a food business operator purchased such from its supplier prior to the aforementioned date, may therefore continue to be used in that Member State even after the trade ban has become applicable. However, the foregoing does not apply to products that were placed on the market in a certain Member State before 3 July 2021, and that are further distributed in another Member State after that date (in the context of a commercial activity). Thus, if a Dutch food company has in stock food packaging covered by the trade ban that it purchased from its supplier prior to 3 July 2021, it can continue using this packaging for food products to be marketed in the Netherlands. However, the Dutch food company can no longer use this packaging for its food products destined for the Spanish market. Although this seems to go against the internal market principles of the EU, the SUP Directive explicitly refers to placing on the market of a Member State (and not on the EU market).

Disposal instructions for beverage cups

Disposal instructions for beverage cups

Conspicuous, clearly legible and indelible marking on plastic products should, since 3 July 2021, ensure that consumers are aware of how to dispose of these and are aware of the negative impact of littering or other improper means of waste disposal on the environment. The European Commission has established marking specifications for this purpose. These markings may be affixed by means of stickers in case of products placed on the market before 4 July 2022. Thereafter, the markings must be printed on the product itself, or on its packaging. The text of the marking must be in the official language(s) of the Member State(s) where the product is marketed. Where the product is marketed in several Member States, it will usually be necessary to include the text of the markings in several languages. Based on Part D of the Annex to the SUP Directive, the above marking requirements apply to beverage cups and several non-food related plastic products.

Other litter-reducing measures

Other litter-reducing measures

The SUP Directive includes many other rules, such as that caps and lids must remain attached to plastic beverage containers during their entire intended use stage (as of 3 July 2024). In addition, beverage bottles must contain at least 25% recycled plastic from 2025, and at least 30% recycled plastic from 2030. However, the above measures only apply to beverage containers and bottles of up to 3 liters. Furthermore, glass and metal beverage bottles with caps and lids made from plastic are exempt from the above rules, as well as such beverage bottles for food for special medical purposes.

In addition, the SUP Directive calls on Member States to take awareness raising measures to prevent and reduce litter, to ensure the separate collection for recycling, to take the necessary measures to achieve consumption reduction, and to establish extended producer responsibility schemes. The latter means, in short, that ‘the polluter pays’ and that the producer or importer thus pays the cost of cleaning up litter. The Annex to the SUP Directive indicates the plastic products to which the above measures apply.

Measures differ between Member States

Although the SUP Directive was adopted at European level, this does not mean that measures to prevent litter and stimulate a circular economy will be the same in all Member States. To achieve reduction in the consumption of single-use plastics, a Member State may for instance set national targets, take measures to ensure that re-usable alternatives are made available at the point of sale to the final consumer, or ensure that single-use plastic food and beverage containers are no longer provided free of charge to the final consumer. Next to the above-mentioned examples, there are many other possibilities that Member States may exploit.

In the Netherlands, the SUP Directive is implemented in the Single-use Plastic Products Decree (in Dutch: Besluit kunststofproducten voor eenmalig gebruik) and in the Packaging Management Decree 2014 (in Dutch: Besluit beheer verpakkingen 2014). To achieve reduction in the consumption of single-use plastics, the Netherlands is keeping open the possibility of no longer providing food packaging and beverage cups (as defined in article 15d of the Packaging Management Decree 2014) free of charge to the final consumer, having available a re-usable alternative to the final consumer at the point of sale and/or prohibiting the provision of the above-mentioned products to the final consumer at certain locations or occasions. Such measures will apply as per 1 January 2023.

Companies operating in several Member States would do well to become familiar with the national measures relevant to them. For plastic products listed in Part E of the Annex to the SUP Directive (including certain single-use food and beverage containers), the Directive even explicitly requires producers that sell such products in a Member State other than where they are established to appoint an authorized representative in the Member State of sale. The authorized representative is responsible for ensuring that the producer’s obligations in the Member State of sale are met.

Alternatives

Although the SUP Directive appears to be a set of restrictions, it is also meant to encourage the production and use of sustainable alternatives to single-use plastic products. For example, food companies that depend on packaging for the shelf life and quality of their products, or to convey information to consumers, may want to explore their options to switch to reusable packaging, to set up collection and recycling systems, or to use other materials such as paper and cardboard (without plastic coating). Of course, such sustainable initiatives should not come at the expense of food hygiene and food safety.

Conclusion

Plastic products are increasingly being restricted to protect the environment and human health. Food companies using packaging consisting wholly or partly of plastic are advised to check whether the packaging they use is covered by the SUP Directive, what measures apply to it and whether alternatives are available. It should also be borne in mind here that measures under the SUP Directive are introduced gradually and may differ per EU Member State. For entrepreneurs who operate intra-Community, the correct implementation of the new rules will require the necessary efforts. But who does not want to move towards a more liveable world and a sustainable production chain? The reduction of plastic could make a valuable contribution to that purpose.

Personalized nutrition as a medical device

Posted: July 8, 2021 | Author: Jasmin Buijs | Filed under: Authors, Disclosure of information, Food, Health claims, Information, Nutrition claims | Comments Off on Personalized nutrition as a medical device From May 26 this year, the personalized nutrition space has been enriched with a new piece of legislation: the Regulation (EU) 2017/745 on medical devices (hereinafter: “MDR”). The MDR is, generally speaking, applicable to all personalized nutrition (software) products, including apps and algorithms, with a medical intended purpose. Since most personal nutrition services that are currently on the market are lifestyle related, they will not be affected by the MDR. This will however be different for services that offer dietary advice for the prevention, alleviation or treatment of a disease. This blogpost aims to provide an introduction to the new rules on personalized nutrition as a medical device.

From May 26 this year, the personalized nutrition space has been enriched with a new piece of legislation: the Regulation (EU) 2017/745 on medical devices (hereinafter: “MDR”). The MDR is, generally speaking, applicable to all personalized nutrition (software) products, including apps and algorithms, with a medical intended purpose. Since most personal nutrition services that are currently on the market are lifestyle related, they will not be affected by the MDR. This will however be different for services that offer dietary advice for the prevention, alleviation or treatment of a disease. This blogpost aims to provide an introduction to the new rules on personalized nutrition as a medical device.

What is the MDR?

The MDR comprises of a set of rules that governs the full medical devices supply chain from manufacturer to end user in order to ensure the safety and performance of medical devices. It applies to any apparatus, application, software or other article intended by the manufacturer to be used for a medical purpose. This includes, like under the old medical devices legislation, the diagnosis, prevention, monitoring, treatment or alleviation of a disease. Since the application of the MDR, also devices designed for the prediction or prognosis of a disease qualify as a medical device. Genetic testing kits for medical purposes and other medical devices to be used in vitro for the examination of specimens such as blood are covered by the MDR’s sister, Regulation (EU) 2017/746 on in-vitro diagnostic medical devices (hereinafter: “IVDR”). The IVDR applies from May 26 next year.

When does the MDR apply to personalized nutrition software?

The essential question for the MDR’s applicability is thus whether the article or software concerned has a medical purpose or is merely lifestyle or well-being related. For example, an app that provides dietary advice based on the users’ preferences and potential health data is a lifestyle product. But if the same app claims to help address obesity or treat hypertension, then it can be linked to a disease and transforms into a medical device. While the intention of the manufacturer of the device is leading for the application of the MDR, it should be noted that only a statement that a product is not a medical device, or is meant for lifestyle purposes only, does not constitute a reason to escape from this regulation. The intended purpose is inferred from every document and statement that expresses the intended purpose, including advertising and marketing material. Disclaiming a medical intended purpose in the instructions for use but claiming such purpose in marketing materials will still result in a finding of a medical intended purpose. The MDR contains an explicit prohibition on statements that may mislead the end user about the intended purpose or ascribes functions or properties to the device that it does not have, which would be caught in its scope.

Another example of a medical device is the wearable being developed by the Australian start-up Nutromics, which assesses dietary biomarkers to provide dietary advice to minimize users’ risk for lifestyle-related chronic diseases. This device is designed to predict the user’s likelihood of developing a particular disease and to subsequently provide advice to prevent such disease, and will therefore be subject to the MDR when placed on the Union market. On the other hand and as clarified earlier by the European Commission in its borderline manual for medical devices, a home-kit that enables the user to ascertain their blood group in order to determine whether a specific diet should be followed falls outside the medical sphere (as defined in the (old) medical devices legislation). The sidenote should however be made that this decision was not related to following a specific diet for medical purposes.

It is also relevant to state that software may as well qualify partly as a medical device and partly as a non-medical device. Think for example of an app that provides the user with personalized nutritional advice as part of the treatment or alleviation of diabetes, and additionally facilitates online contact with fellow patients. While the software module(s) that provide information on the treatment or alleviation of the disease will be subject to the MDR, the software module that is responsible for the contact amongst patients has no medical purpose and will therefore not be subject to the MDR. The manufacturer of the device is responsible for identifying the boundaries and the interfaces of the medical device and non-medical device modules contained in the software. The Medical Device Coordination Group has pointed out in its guidance on qualification and classification of software (October 2019) that if the medical device modules are intended for use in combination with other modules of the software, the whole combination must be safe and must not impair the specified performances of the modules which are subject to the MDR. This means that also the non-medical devices module(s) may have to be covered in the technical documentation that supports the device’s compliance with the MDR and as further introduced below.

Way to market of personal nutrition software

All medical devices placed on the Union market must in principle have a CE (conformité européenne) marking as proof of compliance with the law. To apply the CE-mark, the manufacturer has to prepare technical documentation and carry out a conformity assessment procedure, including clinical evaluation. The specific procedure that must be followed depends on the risk class of the device. The MDR distinguishes the risk classes I, IIa, IIb and III (from low to high). The higher the risk class of the device, the more stringent requirements for clinical evaluation apply to demonstrate safety, performance and clinical benefits. It could ironically be stated that MDR stands for More Data Required: where an analysis of available clinical data from literature may have been sufficient in the past, the MDR more often requires own clinical investigations to support the device’s safety and performance.

Under the MDR, software as medical device is classified as class IIa when it is intended to provide information which is used to take decisions with diagnosis or therapeutic purposes, or to monitor physiological processes. Translated to personal nutrition services, this would for instance include apps that track burned calories (monitoring of physiological processes) and that provide dietary advice as part of a treatment (therapeutic purposes). Risk increasing factors will however lead to a higher risk class than class IIa. While an app with which food products’ barcodes can be scanned to detect certain ingredients for allergen control purposes would normally be a class IIa device, it will be a class III device when food intake decisions based on the app may cause life-threatening allergic reactions when based on a false negative (safe to eat while it in fact is not safe).

All other software which is not specifically addressed but still has a medical intended purpose in scope of the definition of a medical device, is classed as class I. An example would be an app that provides nutritional support with a view to conception. The risk classification rules for software are new under the MDR, which means that existing medical devices software may be scaled in a higher risk class since 26 May 2021. This is relevant not only with regard to the conformity assessment procedure that must be followed, but also to the question who can perform the required assessment of legal compliance. Manufacturers of devices in a higher class than class I must always engage a so-called notified body in this regard, while class I devices can in principle be self-certified by the manufacturer. An exception exists however for class I devices that have a measurement function, for example by using the lidar of the user’s phone to measure the body as input for the functionality of the app, which also require the engagement of a notified body.

Take away for food businesses

When personal nutrition enters into the medical sphere, the MDR will come into play. This will impact first and foremost the manufacturers, importers and distributors of actual medical devices, including apps and algorithms. Having said that, food businesses that wish to market their food products through medical devices apps are advised to be aware of the implications thereof. This will help them to find a reliable partner and to ensure their interests are contractually protected.

A more elaborate version of this blogpost has been published at Qina in cooperation with Mariette Abrahams.

CBD as a food product: no drug, isn’t it? The interaction between food and opium legislation.

Posted: March 5, 2021 | Author: Jasmin Buijs | Filed under: Authors, cannabidiol, cannabis, Food | Comments Off on CBD as a food product: no drug, isn’t it? The interaction between food and opium legislation. A number of legal developments in the field of cannabidiol (CBD) took place in the last few months of the previous year. For example, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled in November that a member state cannot prohibit the marketing of CBD that was lawfully manufactured and marketed in another member state. Less than a month later, the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) voted on six recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) regarding the reclassification of cannabis in the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (Single Convention). In practice, there appears to be confusion about the meaning of these developments for CBD as a food product. This confusion seems to arise from the interaction between food and opium legislation, both of which are applicable to this product. This article aims to provide clarity on these latest developments.

A number of legal developments in the field of cannabidiol (CBD) took place in the last few months of the previous year. For example, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled in November that a member state cannot prohibit the marketing of CBD that was lawfully manufactured and marketed in another member state. Less than a month later, the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) voted on six recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) regarding the reclassification of cannabis in the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (Single Convention). In practice, there appears to be confusion about the meaning of these developments for CBD as a food product. This confusion seems to arise from the interaction between food and opium legislation, both of which are applicable to this product. This article aims to provide clarity on these latest developments.

CBD is not a narcotic according to the ECJ

On 19 November 2020, the ECJ ruled, in summary, that the free movement of goods entails that when CBD is lawfully manufactured and marketed in one member state, it may, in principle, also be marketed in another member state. This is, however, different when Article 36 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) justifies an exception to the free movement of goods, such as for the protection of health and life of humans. Yet, the trade restricting or prohibiting measure must in such a case be appropriate for securing the attainment of the objective pursued (the protection of health and life of humans) and must not go beyond what is necessary in order to attain it. To reach the aforementioned conclusion, the preliminary question had to be answered whether CBD falls within the scope of the free movement of goods. This principle does namely not apply to narcotics, which are prohibited throughout the Union (with the exception of strictly controlled trade for use for medical and scientific purposes). Based on the Single Convention and the Convention on Psychotropic Substances, the ECJ reasoned that CBD is subject the free movement of goods. Both conventions codify internationally applicable control measures to ensure the availability of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances for medical and scientific purposes and to prevent them from entering illicit channels. The Convention on Psychotropic Substances regulates psychoactive substances, whether natural or synthetic, and natural products listed in the schedules to the Convention, including tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). CBD is not included. The Single Convention applies, inter alia, to cannabis (defined as “the flowering or fruiting tops of the cannabis plant (excluding the seeds and leaves when not accompanied by the tops) from which the resin has not been extracted, by whatever name they may be designated”). Although a literal interpretation of the above provision would lead to the conclusion that CBD (not obtained from the seeds and leaves of the cannabis plant) falls within the definition of cannabis, such an interpretation is not consistent with the purpose of the Single Convention, namely protecting the health and welfare of mankind. Indeed, according to the current state of scientific knowledge, CBD is not a psychoactive substance.

UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs reclassifies cannabis

Shortly after the ECJ ruling regarding, among others, the Single Convention, the CND put six WHO recommendations to vote on 2 December 2020. This voting session would have taken place earlier, though had been postponed so that the voting countries had more time to study the matter and to determine their position. The WHO recommendations dealt with the reclassification, removal and addition of cannabis (substances) in the various schedules (Schedule I, II, III and IV) to the Single Convention. These four schedules represent four categories of narcotics and each category has its own rules. The substances in Schedule VI are  controlled most strictly; they are considered dangerous without relevant medicinal applications. Schedule I concerns the second most strictly controlled category. The substances in this Schedule are subject to a level of control that prevents harm caused by their use while not hindering access and research and development for medical use. The lightest criteria apply to Schedule II and III. For example, Schedule II lists substances normally used for medicinal purposes and with a low risk of abuse.

controlled most strictly; they are considered dangerous without relevant medicinal applications. Schedule I concerns the second most strictly controlled category. The substances in this Schedule are subject to a level of control that prevents harm caused by their use while not hindering access and research and development for medical use. The lightest criteria apply to Schedule II and III. For example, Schedule II lists substances normally used for medicinal purposes and with a low risk of abuse.

Bedrocan (currently the sole supplier of medicinal cannabis to the Dutch government) has summarized these six WHO recommendations as follows:

- Extracts and tinctures are removed from Schedule I.

- THC (dronabinol) is added to Schedule I under the category Cannabis & Resin. Subsequently, THC is removed from Schedule II of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

- THC isomers are added to Schedule I under the category Cannabis & Resin. Subsequently, THC isomer is removed from the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

- Pure CBD and CBD preparations with maximum 0.2 % THC are not included in the international conventions on controlling drugs.

- If they comply with certain criteria, pharmaceutical preparations that contain delta-9-THC should be added to Schedule III, recognizing the unlikelihood of abuse and for which a number of exemptions apply.

- Cannabis and cannabis resin are removed from Schedule IV, the category reserved for the most dangerous substances.

In the end, only the recommendation to remove cannabis from Schedule IV (i.e., recommendation 6) was approved, on the grounds that there are also positive aspects to cannabis. However, this does not mean that cannabis can now be freely traded. Cannabis is still included in Schedule I and is therefore in principle a prohibited substance. Having said that, research and product development for medical purposes is permitted if a country so desires. In the Netherlands, the Dutch Opium Act already allowed for this under certain conditions. The reclassification of cannabis is therefore more symbolic in nature than that it brings about practical changes.

The recommendation to explicitly exclude CBD from the scope of the Single Convention has thus been rejected. The industry considers this a missed opportunity to clarify the (legal) status of CBD with traces of THC. This rejection was on the other hand in line with the viewpoint of the European Commission, which advised its member states that sit on the CND (i.e. Belgium, Germany, France, Hungary, Italy, Croatia, the Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Spain, Czech Republic and Sweden) to vote against this recommendation since more research would be needed. For example, the European Commission takes the position that the proposed THC limit of 0.2 % is not sufficiently supported by scientific evidence. The WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence (ECDD) notes in this regard that medicines without psychoactive effects that are produced as preparations from the cannabis plant will contain traces of THC and provides the example of the CBD preparation Epidiolex as approved for the treatment of childhood-onset epilepsy, which contains no more than 0.15 % THC by weight. At the same time, WHO ECDD recognizes that it may be difficult for some countries to conduct chemical analyses of THC with an accuracy of 0.15%. Hence, it recommends the limit of 0.2 % THC. This limit is already known to food companies from the so-called Novel Food Catalogue of the European Commission, which recalls that in the EU, the cultivation of Cannabis sativa L. varieties is permitted provided they are registered in the EU’s ‘Common Catalogue of Varieties of Agricultural Plant Species’ and the THC content does not exceed 0.2 % (w/w). This does, however, not necessarily mean that products derived from such cannabis varieties can be freely marketed as food.

CBD as food product

With respect to cannabis extracts such as CBD, as well as its synthetic equivalent, no history of safe use has been demonstrated. As a result, these products qualify as novel foods and can only be placed on the EU market after approval by the European Commission. Several food companies such as the Swiss company Cibdol AG, Chanelle McCoy CBD LTD from Ireland and the Czech CBDepot, have already applied for the required novel food authorization. However, the assessment of the relevant dossiers has been paused, presumably because it was still unclear whether CBD qualified as a psychotropic substance and narcotic. Such a qualification would exclude use as a foodstuff. Thanks to the ECJ ruling, this has now been clarified, on the basis of which the European Commission will likely resume the evaluation of the various applications for CBD as a novel food.

CBD under the Dutch Opium Act

A potential approval of CBD as a novel food does, however, not automatically mean that CBD can be sold in the EU without any (legal) obstacles. The Novel Food Catalogue makes this reservation explicit by indicating that specific national legislation, other than food legislation, may restrict the placing on the market of a cannabis product as a food. In practice, it will in particular come down to opium legislation.

Although the ECJ clarified that CBD is not a narcotic, it did not specify how pure CBD must be to fall outside the scope of the Single Convention and to be freely traded. The respective rejected WHO recommendation referred to a THC content of up to 0.2 %. In the Netherlands is, however, only a contamination level of < 0.05 % allowed. This impurity can be caused by traces of THC, but also by the presence of other cannabinoids. Only pure CBD, i.e. with a purity level of > 99.95 %, falls outside the scope of the Dutch Opium Act. Having said that, there is another catch: although the Dutch Opium Act does not cover CBD, this Act is applicable to the cannabis plant (or its parts) from which the CBD is extracted. The production of (natural) CBD can therefore not take place in the Netherlands.

Conclusion

Recent developments in the field of CBD have clarified that CBD is not a narcotic and therefore does not fall under the Single Convention. Food businesses are nevertheless warned to not yet start celebrating. If they want to market CBD as a food, they will still have to go through the novel food procedure, or market a product in accordance with the terms of an already approved CBD product. The latter is possible insofar data protection does not prevent this. Besides this, the purity level of CBD is decisive to stay away from opium legislation. There is still no international agreement on what this level should be. Food businesses operating in different member states are therefore advised to seek local advice when marketing CBD in the EU.

Active disclosure of inspection results: how to prevent naming & shaming?

Posted: October 2, 2020 | Author: Jasmin Buijs | Filed under: Authors, cannabidiol, cannabis, Disclosure of information, Enforcement, Food, Food Supplements, Health claims | Comments Off on Active disclosure of inspection results: how to prevent naming & shaming? Since 1 September 2020, the Dutch Food Safety Authority (NVWA) has been given the power to publish certain inspection results (including identification details of the inspected FBO) faster than before. Prior to that date, the legal basis for disclosure could primarily be found in article 8 of the Dutch Freedom of Information Act (in Dutch: Wet openbaarheid van bestuur). This act creates a duty for the administrative body concerned, for example the NVWA, to publicly provide information when this is in the interest of good and democratic governance. However, article 10 of the Freedom of Information Act requires an individual balancing of interests in order to avoid disproportionate disadvantage for the parties involved as a result of the publication. It also prohibits disclosure of certain sensitive information, such as company and manufacturing data that has been confidentially communicated to the government. This blog post explains what has changed since 1 September 2020, which FBOs are affected and what arguments they can use to prevent disclosure.

Since 1 September 2020, the Dutch Food Safety Authority (NVWA) has been given the power to publish certain inspection results (including identification details of the inspected FBO) faster than before. Prior to that date, the legal basis for disclosure could primarily be found in article 8 of the Dutch Freedom of Information Act (in Dutch: Wet openbaarheid van bestuur). This act creates a duty for the administrative body concerned, for example the NVWA, to publicly provide information when this is in the interest of good and democratic governance. However, article 10 of the Freedom of Information Act requires an individual balancing of interests in order to avoid disproportionate disadvantage for the parties involved as a result of the publication. It also prohibits disclosure of certain sensitive information, such as company and manufacturing data that has been confidentially communicated to the government. This blog post explains what has changed since 1 September 2020, which FBOs are affected and what arguments they can use to prevent disclosure.

Additional basis of disclosure as of 1 September 2020

As of 1 September 2020, the NVWA is additionally bound by the Decree on the Disclosure of Supervision and Implementation Data under the Health and Youth Act (in Dutch: Besluit openbaarmaking toezicht- en uitvoeringsgegevens Gezondheidswet en Jeugdwet, hereinafter: Decree on Disclosure), as further elaborated in the Policy Rule on Active Disclosure of Inspection Data by the NVWA (in Dutch: Beleidsregel omtrent actieve openbaarmaking van inspectiegegevens door de NVWA, hereinafter: Policy Rule on Disclosure). This power of disclosure is based on article 44 of the Dutch Health Act (in Dutch: Gezondheidswet). Disclosure in accordance with the Decree on Disclosure does not require the balancing of interests: disclosure of information will simply take place when indicated in the relevant annex to the Decree on Disclosure. Companies that wish to prevent publication of information related to their business will therefore have to invoke factual criteria, such as that the information to be disclosed contains incorrect information or concerns information that is excluded from disclosure in Article 44(5) of the Health Act.

Required actions when companies disagree with disclosure

The publication of information as based on the Decree on Disclosure has consequences for the way affected companies can stand up to prevent disclosure and the speed with which they will need to object. Where the Freedom of Information Act offers affected companies the possibility to share their opinion (in Dutch: zienswijze) in reaction to the administrative body’s intention to disclose the information in question, this possibility does not exist under the Decree on Disclosure. If and when an affected company does not agree with disclosure on the basis of the latter decree, this company has two weeks to object to the respective administrative body’s intention of disclosure and needs to seek interim relief measures within this time frame in order to actually suspend the disclosure. In addition, under the Decree on Disclosure companies are provided the option to write a short response that will be published together with the information subject to disclosure. In this way, affected companies are given the opportunity to provide the outside world with a substantive (but very summary) response to the information to be made public. The Policy Rule on Disclosure in fact also grants this right of response to information disclosed by the NVWA under the Freedom of Information Act.

Relevant for all FBOs?

The aforementioned additional legal basis for disclosure by the NVWA applies for the time being to a limited number of supervisory areas only, namely the inspection results of the NVWA with regard to (i) fish auctions, (ii) the catering industry, and (iii) project-based studies into the safety of goods other than food and beverages. These areas may be expanded in the future, according to the explanatory notes to the Decree on Disclosure.

However, for companies with so-called borderline products that navigate between different regulatory regimes, it is relevant to know that Dutch Health and Youth Care Inspectorate (IGJ) has broader powers to actively disclose inspection results under the Decree on Disclosure. Since 1 February 2019, the IGJ has already been publishing information on the basis of this decree regarding, amongst other, compliance with the Dutch Medicines Act (in Dutch: Geneesmiddelenwet). This means that when the IGJ takes enforcement measures against a FBO handling food supplements or other foodstuffs that qualify as (unregistered) medicines, it may be obliged to make public the respective supervisory information. The same applies to enforcement under the Dutch Medical Devices Act (in Dutch: Wet op de medische hulpmiddelen) – think diet preparations – and the Opium Act (in Dutch: Opiumwet) – think CBD and other cannabis products.

However, for companies with so-called borderline products that navigate between different regulatory regimes, it is relevant to know that Dutch Health and Youth Care Inspectorate (IGJ) has broader powers to actively disclose inspection results under the Decree on Disclosure. Since 1 February 2019, the IGJ has already been publishing information on the basis of this decree regarding, amongst other, compliance with the Dutch Medicines Act (in Dutch: Geneesmiddelenwet). This means that when the IGJ takes enforcement measures against a FBO handling food supplements or other foodstuffs that qualify as (unregistered) medicines, it may be obliged to make public the respective supervisory information. The same applies to enforcement under the Dutch Medical Devices Act (in Dutch: Wet op de medische hulpmiddelen) – think diet preparations – and the Opium Act (in Dutch: Opiumwet) – think CBD and other cannabis products.

An example: melatonin-containing foodstuff labeled as a medicine

An example: melatonin-containing foodstuff labeled as a medicine

An example of a FBO that was faced with disclosure in accordance with the Decree on Disclosure by the IGJ concerns a company involved in melatonin-containing products. The IGJ intended to publish an inspection report on these products, from which it would follow that the products in question qualify as medicines and that the FBO concerned would therefore illegally place them on the market (namely without the required licenses under the Medicines Act). The FBO at stake applied for a preliminary injunction suspending the publication decree. On 8 July 2020, the preliminary relief judge rendered a judgment in this case.

Possible factual criteria to prevent naming & shaming

Although disclosure under the Decree on Disclosure is obligatory and disclosure decisions thus do not require the balancing of interests, the above-mentioned melatonin case gives good insights into the factual criteria that can nevertheless be invoked to prevent disclosure. In this case, the respective FBO brought forward the following arguments.

The respective inspection report excluded from disclosure

Article 3.1(a) of Part II of the Annex to the Decree on Disclosure excludes certain supervisory information from disclosure, including the results of inspections and investigations established as a result of a notification by a third party. The FBO at stake (hereinafter: “Applicant’) takes the position that the present inspection report was initiated as a result of a notification or enforcement request by a competitor. This would mean that the respective inspection report must not be made public.

The preliminary relief judge cannot agree with this position in the present case and rules that the inspection report is clearly related to an earlier letter from the IGJ to the applicant in which it announced the intensification of supervision of melatonin-containing products. Moreover, the case file was silent on a notification or enforcement request by a competitor.

The preliminary relief judge additionally states that it agrees with the IGJ’s viewpoint that the inspection report does not concern a penalty report (the report was drafted within the context of supervision and only indicates that Applicant will be informed about the to be imposed enforcement measure by separate notice). The fact that Applicant had earlier received a written warning for violation of the Medicines Act has no influence on this. The inspection report is therefore neither excluded from publication pursuant to article 3.1(a)(ii) of Part II of the Annex to the Decree on Disclosure, which makes an exception for “results of inspections and investigations that form the basis of decisions to impose an administrative fine”.

Disclosure in violation of the goal of the Health Law: outdated scientific foundation conclusions IGJ

The purpose of disclosure under the Health Act, in the wording of article 44(1) of that act, is to promote compliance with the regulations, to provide the public with insight into the way in which supervision and implementation of the Decree on Disclosure is carried out and into the results of those operations. Pursuant to Article 44a(9) of the Health Act, information should not be made public where this is or may violate aforementioned purpose of disclosure. Applicant takes the position that publication of the present inspection report does not contribute to improved protection of the public or to better information about the effects of melatonin, as a result of which the report should not be disclosed. More specifically, the applicant complains that the report (i) contains obvious errors and inaccuracies, (ii) gives the impression that it concerns a penalty decision, and (iii) is based on an incorrectly used framework to determine whether the qualification of a medicine is met.

The preliminary relief judge first of all notes that the fact that Applicant does not agree with the conclusions of the inspection report does not mean that the report therefore contains obvious inaccuracies. The preliminary relief judge further summarizes Applicant’s position as follows: (i) the IGJ wrongly took a daily dosage of 0.3 mg melatonin to determine the borderline between foodstuff and medicines; (ii) in doing so, the IGJ did not demonstrate that products with a daily dose of 0.3 mg melatonin actually acts as a medicine; (iii) moreover, the product reviews refer to outdated scientific publications (a more recent study by one of the authors thereof as well as more recent EFSA reports have not been included in the inspection report), whereas the current state of scientific knowledge must be taken into account according to established case-law. For these reasons, the preliminary relief judge agreed with Applicant that the IGJ has not made it sufficiently clear that from a daily dose of melatonin of 0.3 mg or more a ‘significant and beneficial effect on various physiological functions of the body’ occurs scientifically – according to the current state of scientific knowledge – and that products with a daily dose of melatonin of 0.3 mg or more act as a medicine”. Having said that, the preliminary relief judge did not accept Applicant’s statement that disclosure is contrary to the purpose of disclosure under the Health Act. Instead, the preliminary relief judge sought to comply with the so-called principles of sounds administration (in Dutch: algemene beginselen van behoorlijk bestuur) and ruled that the disclosure decision was not diligently prepared and insufficiently substantiated.

Incorrect facts

Applicant claims that the inspection report contains various inaccuracies, including the incorrect information that Applicant would produce melatonin itself. Applicant had already raised these inaccuracies in her response to the draft version of the report, but this had not resulted into adjustments in the final, to be published version of the report. The preliminary relief judge ruled on this matter that the IGJ should further investigate Applicant’s concerns and should amend the report where relevant. After all, the content of the report must be correct and diligently compiled. The mere fact that Applicant was given the opportunity to respond to the draft version of the report and that the IGJ responded to this in its decision to disclose the report does not mean that this requirement is met.

Violation of article 8 ECHR: disclosure has a major impact on Applicant’s image

Applicant claims that the planned disclosure will have a major impact on Applicant’s image and that of the natural person involved in the company. This is in violation of article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) concerning the right to respect for private and family life. The Explanatory Memorandum to the Amendment to the Health and the Youth Care Act (in Dutch: Memorie van Toelichting op de Wijziging van de Gezondheidswet en de Wet op de Jeugdzorg) deals with this in detail. It emphasizes that the disclosure of inspection data does normally not constitute an interference with private life, because the data normally relates to legal persons and not to natural persons. The aforementioned Explanatory Memorandum therefore concludes that article 8 ECHR does not preclude disclosure on the grounds of the Health Act. Nevertheless, the court has at all times the competence to review a disclosure decision in the light of that article, in which case it will in fact have to balance the interests involved. In the present case, preliminary relief judge sees however no reason to assume a violation of article 8 ECHR.

Although the above shows that the preliminary relief judge in the respective melatonin case does not agree with all arguments put forward by Applicant, the request for suspension of publication of the contested inspection report was nevertheless granted thanks to factual criteria that were sufficiently substantiated. In particular the (implicit) argument that the conclusions in the inspection report lack a sufficient factual basis affects the essence of the information to be disclosed.

Conclusion

Rapid action is required to prevent active disclosure of inspection results under the Decree on Disclosure as these will usually be published after two weeks. This is not only relevant for FBOs active in the supervisory areas of the NVWA as designated in the Decree on Disclosure, but also for FBOs that operate at the interface of legal regimes under the supervision of the IGJ. To suspend disclosure, interim relief proceedings will have to be instituted as the Decree on Disclosure no longer provides for the possibility of submitting an opinion prior to publication. Moreover, affected companies cannot invoke the argument of suffering a disproportionate disadvantage as a result of the publication. Publication on the basis of the Decree on Disclosure is namely not subject to an individual balancing of interests (apart from an assessment on the basis of article 8 ECHR, insofar relevant). Although the arguments that companies can bring forward to prevent publication are therefore more limited than in the case of disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act, this does not mean that companies cannot successfully object an intention of disclosure. The melatonin case mentioned above is an example of this: conclusions that are not based on most recent science may not be published without adequate justification. Also, facts that are alleged to be incorrect should be further investigated before disclosure.

Towards 100 % recyclable or re-usable plastic food packaging in 10 years

Posted: May 4, 2020 | Author: Jasmin Buijs | Filed under: Authors, Food, Information | Comments Off on Towards 100 % recyclable or re-usable plastic food packaging in 10 yearsWhat would food be without packaging? And what does packaging mostly consist of? Of course: plastic! To date, only few other materials have proved as reliable for food packaging as plastic. At the same time, we know that plastic has many disadvantages for the environment. Read this blogpost to be informed on the most important initiatives of the food sector and on the legal tools of the European Commission in this field.

The visionary n umber of 2030

umber of 2030

By 2030, all plastic packaging in the EU will be recyclable or re-usable. In other words, all plastic packaging will then be collected and transformed into new packaging materials, or can be used as such more once. This goal follows, amongst others, from the European Strategy for Plastics. It is a worthy endeavor, and for some it is not even ambiguous enough. The signatories of the Plastics Pact aim to achieve this result as early as 2025. Nestlé has also announced its ambition to make 100% of its packaging recyclable or re-usable by 2025. Since this year, Lipton bottles sold in the Netherlands are already made from 100% recycled plastic. The so-called European Single-use plastics Directive (Directive 2019/904) will soon be introduced to further promote recycling of plastics as one of the measures against disposable plastics. In the Netherlands, this Directive will be implemented by means of a General Administrative Order (in Dutch: Algemene Maatregel van Bestuur, or “AMvB”) before the Directive’s date of application on 3 July 2021. In this regard, an internet consultation will be launched this month to invite citizens, companies and institutions to make suggestions to improve the quality and feasibility of the current proposal.

Recycled materials and articles

The encouragement to use recycled materials and articles in the EU for environmental reasons was already expressed in recital 24 of the European framework legislation on food contact materials (Regulation 1935/2004). However, food safety and consumer protection should not be neglected. Therefore, food packaging materials, including recycled plastics, should not endanger human health and not adversely affect the composition of foods or their sensory properties in an unacceptable way. The above-mentioned framework legislation leaves room for detailed rules on specific materials, and priority has been given to rules on recycled plastics. Their use has been increasing for a long time. Indeed, today’s sustainability initiatives cannot be imagined without the recycling of plastic food packaging. Moreover, diverging national legislation on this topic as a consequence of no harmonization at EU level would be highly undesirable.

Specific legislation

Specific rules on recycled plastic materials and articles intended to come into contact with foods can be found in Regulation 282/2008. Such rules are important because plastic packaging waste can be contaminated by residues from previous use, but also by contaminants from misuse and from non-authorized substances. In order to ensure that possible contamination is removed and that recycled plastics therefore do not adversely affect human health and foodstuffs with which they come into contact, an appropriate sorting and recycling process is essential. It should be noted that Regulation 282/2008 refers to mechanical recycling, which does not involve any significant change in the chemical structure of the plastic material. This process is less suitable for composites and multilayered plastics, which means that not all plastics are eligible for recycling under Regulation 282/2008.

Authorization procedure plastic recycling processes in a nutshell

Before a recycling process can be applied to plastics to create food packaging, the process must be approved by the European Commission. Such authorizations are process specific. This means that authorizations cover a specific recycling process used in a specific company by applying specific technologies and process parameters. Authorization holders are of course free to license out the authorized recycling process to other companies. Applications for the approval of recycling processes shall be submitted to the competent authority at Member State level. The European Commission published a list of contact points for competent authorities. In the Netherlands, applications can be submitted to the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport (in Dutch: Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport, or “VWS”) and the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (in Dutch, Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu, or “RIVM”).

As part of the application, a technical dossier is to be provided. This dossier will subsequently be subject to a safety assessment by EFSA, followed by a scientific opinion. In fact, here we very much see the parallel with the safety evaluations EFSA performs regarding for instance Novel Foods and additives. Topics to be covered to evaluate the safety of a particular recycling process include input characterization, description of the recycling process, determination of the decontamination efficiency of the recycling process, output characterization, and intended application in contact with food. For example, the dossier must demonstrate that and how it is ensured that the input material does not contain any chemical substances that could survive the recycling process and migrate to our foods in irresponsible quantities. In order to evaluate potential migration, detailed information on the type of food(s) intended to come into contact with the final product shall be provided. This will also include information on time, temperature and contact surface. Another important aspect concerns single or repeated use of the final product. All of this data serves to exclude possible health hazards and unacceptable influences on foods due to migration of substances. Further details can be found in the guidelines published by EFSA.

After receipt of a valid dossier, EFSA has, in principle, six months to evaluate the dossier. Thereafter, it is up to the European Commission to take an authorization decision. In doing so, it will take into account EFSA’s scientific advice. The final authorization may be subject to conditions and/or restrictions, such as with regard to the plastic input, the recycling process and/or the field of application of the recycled plastic. Authorized recycling processes are listed in a Community register established by the European Commission.

100% R ecyclable

ecyclable

Many companies like to inform consumers that the food packaging they use is made from recycled plastics. However, it is essential that consumers are not misled about, for example, the actual content of recycled plastics used. Companies are therefore advised to follow ISO 14021 on environmental labels and declarations, or equivalent rules. In addition, the Dutch Advertising Code Committee (in Dutch: Reclame Code Commissie, or “RCC”) also explains what is possible and what is not, such as regarding packaging made of recycled plastics being environmentally friendly or friendlier. Environmental claims, i.e. advertisements in which implicit or explicit reference is made to environme ntal aspects associated with the production, distribution, consumption or waste processing of goods or services, must be verifiable. For instance, communicating that an article is “good for nature” because of the material used is perceived as misleading when this statement cannot be checked. It is no problem to use environmental symbols, as long as there is no confusion about the symbol’s origin and meaning. Examples of this include the Mobius Loop accompanied by the percentage of recycled material used in or near the symbol, as well as Lipton’s variation thereof.

ntal aspects associated with the production, distribution, consumption or waste processing of goods or services, must be verifiable. For instance, communicating that an article is “good for nature” because of the material used is perceived as misleading when this statement cannot be checked. It is no problem to use environmental symbols, as long as there is no confusion about the symbol’s origin and meaning. Examples of this include the Mobius Loop accompanied by the percentage of recycled material used in or near the symbol, as well as Lipton’s variation thereof.

Conclusion

While food business operators shall normally not be involved in the recycling of packaging themselves, they are advised to closely follow developments in this regard. Packaging namely plays an essential role in protecting foodstuffs and in providing information about the food it contains. Food business operators will therefore benefit from being aware of sustainable packaging possibilities. Moreover, food business operators can strengthen their legal position by being familiar with the legal requirements of the parties they cooperate with as well as with their own responsibilities set out by law. An example of the latter concerns making verifiable and non-misleading environmental claims, which is not always as easily done as said.

Transparency vs. Confidentiality: EFSA’s new role as from March 2021

Posted: July 31, 2019 | Author: Jasmin Buijs | Filed under: Authors, Food, Information, novel food | Comments Off on Transparency vs. Confidentiality: EFSA’s new role as from March 2021 Last month, the European Council formally adopted the new Regulation on the transparency of the EU risk assessment in the food chain, which will be applicable as of 26 March 2021. As is in the name, the new provisions aim at increased transparency of EU risk assessment, which for a large deal means strengthening the reliability, objectivity and independence of the studies used by European Food Safety Authority (“EFSA”). As EFSA has been accused more than once of conflicts of interest, this is, in principle, a welcome development. For FBOs, the implications are however important – as will be demonstrated below.

Last month, the European Council formally adopted the new Regulation on the transparency of the EU risk assessment in the food chain, which will be applicable as of 26 March 2021. As is in the name, the new provisions aim at increased transparency of EU risk assessment, which for a large deal means strengthening the reliability, objectivity and independence of the studies used by European Food Safety Authority (“EFSA”). As EFSA has been accused more than once of conflicts of interest, this is, in principle, a welcome development. For FBOs, the implications are however important – as will be demonstrated below.

The upcoming changes follow from the Commission Communication on the European Citizens Initiative on glyphosate, in which initiative EU citizens called for more transparency in scientific assessments and decision-making, and build upon the findings of the fitness check of the General Food Law. The new provisions will mainly amend the General Food Law. For reasons of consistency, the new provisions also introduce changes to eight legislative acts dealing with specific sectors of the food chain, including the Novel Food Regulation, the Additives Regulation and the GMO Regulation. Based on the publicly available proposal for the meanwhile adopted provisions on the transparency of EU risk assessment, this blogpost provides an overview of what applicants will be facing in authorization procedures for innovative food products in terms of transparency and confidentiality.

Pre-submission phase: union register of commissioned studies and general advice

Before submitting an authorization application, for instance for a Novel Food like cultured meat or insects or for a new additive, applicants will have to notify EFSA of any study they commissioned to support a future authorization application. These studies will become part of the union register of commissioned studies as managed by EFSA. The submitted studies will be made public only when an actual application follows and insofar the studies do not contain confidential information, regarding which a request for confidential treatment has been granted. The idea behind the union register is that companies (potentially) applying for an authorization submit all related information, which subsequently allows EFSA to cross-check the information on the studies performed. This way, applicants can no longer hold back unfavorable studies. This notification obligation also applies to laboratories in the EU that carry out those studies, but obviously not to non-EU laboratories as they fall outside the scope of new provisions. According to the EC’s fact sheet of 13 June 2019, consequences of non-compliance with the notification obligation shall result in a negative temporary stop in the risk assessment.

At the same time, applicants have the right to request EFSA for advice on the relevant provisions and the required content of the application for authorization in the pre-submission phase. This procedure is a response to industry demand, especially of SMEs, for further support in the preparation of applications. The advice shall, however, be provided without the input of the Scientific Panels that are in charge of the actual scientific assessment and shall not cover the specific design of a study. Furthermore, EFSA’s advice shall be made public. Based on the publicly available proposal for the transparency provisions, it seems that this will be done before an actual authorization application is being submitted.

Submission phase: citizens’ access to studies vs. confidentiality

The default setting under the new provisions is that all scientific data, studies and other information supporting applications for authorizations shall be made public by EFSA. While the new provisions aim at ensuring that stakeholders and the public have access to key safety related information being assessed by EFSA, duly justified confidentiality information shall not be made public. The new rules specify which types of information may be considered as such. As listed in the publicly available proposal, this includes production methods, the quantitative composition of the substance or product at stake, certain commercial relationships and other sensitive business information. It is the responsibility of the applicant to demonstrate that making public the information concerned would significantly harms the (commercial) interests concerned. Only in very limited and exceptional circumstances relating to foreseeable health effects and urgent needs to protect human health, animal health or the environment, confidential information shall be disclosed.

The default setting under the new provisions is that all scientific data, studies and other information supporting applications for authorizations shall be made public by EFSA. While the new provisions aim at ensuring that stakeholders and the public have access to key safety related information being assessed by EFSA, duly justified confidentiality information shall not be made public. The new rules specify which types of information may be considered as such. As listed in the publicly available proposal, this includes production methods, the quantitative composition of the substance or product at stake, certain commercial relationships and other sensitive business information. It is the responsibility of the applicant to demonstrate that making public the information concerned would significantly harms the (commercial) interests concerned. Only in very limited and exceptional circumstances relating to foreseeable health effects and urgent needs to protect human health, animal health or the environment, confidential information shall be disclosed.

Specific sectoral food legislation will also include a list of certain types of information that may be treated confidentially. For example, a proposed change to the GMO Regulation includes the specification that certain DNA sequence information and breeding patterns and strategies may be treated confidentially. Next to the confidentiality rules, existing intellectual property rights, data protection rights and data exclusivity provisions for proprietary data, remain applicable.

When an applicant submits a request for confidentiality, it shall

provide a non-confidential version and a confidential version of the submitted information. If and when EFSA receives the submitted information, for example in case the Commission requires a scientific opinion as part of a novel food procedure, it shall publish the non-confidential version without delay and shall decide on the requested confidentiality within 10 days. Insofar the confidentiality request has not been accepted, EFSA shall subsequently publish the additional information after 2 weeks from the notification of its decision. Applicants that do not agree with EFSA’s decision may, under certain circumstances, challenge the decision before the Court of Justice of the European Union.

Once EFSA has published all the non-confidential information and before it carries out its scientific assessment, EFSA may consult third parties, including citizens, to identify whether other relevant information is available on the substance at stake. This new provision serves to mitigate the public concerns that EFSA’s assessment is primarily based on industry studies, more in particular on studies ordered by the applicant. The results of these consultations shall also be made public, as will be minority opinions to EFSA’s scientific output.

Renewals

In case of a request for the renewal of an authorization, the applicant of the renewal will have the obligation to inform EFSA on its planned studies under the new rules. EFSA shall subsequently consult stakeholders and the public on the planned studies and, taking into account the received comments, provide the applicant with advice on the content of the intended renewal application. The reason behind this pre-submission procedure is to make use of the existing experience and knowledge on the substance or product in question. The European Commission expects that the notification obligation will have a positive effect on the evidence base of EFSA, avoids the unnecessary repetition of studies, and will provide the potential applicant with useful advice. It should, however, be noted that also in this case EFSA’s advice will not stand in the way of the subsequent assessment of the renewal application by the Scientific Panels.

Additional controls on the conduct of studies

The new provisions also include measures to ensure the quality and objectivity of the studies used by EFSA for its risk assessment. First of all, the European Commission will have the right to perform controls, including audits, to verify the compliance of testing facilities with relevant standards. Competent authorities of the Member States will be involved in these controls. Through coordination with OECD GLP auditing programs, the control in non-EU countries will be facilitated as well. Secondly, the European Commission will have the right to request EFSA to commission verification studies. Such action shall only be taken in exceptional circumstances, such as in case of serious controversies or conflicting results, and will be financed by the EU.

Conclusion

The new provisions address public concerns regarding transparency, while on the other hand acknowledge that confidentiality is key to not cut down on incentives for innovation by food businesses. In other words: the new provisions seek to balance transparency and confidentiality. Food businesses are advised to substantively consider their commercial interests when submitting a dossier for authorization, since confidentiality will only be granted upon duly justified requests. Moreover, the union register for submitted studies forces food businesses to carefully plan their studies at an early stage since also studies with less favorable outcomes will in principle be made public and scrutinized on inconsistencies with later studies. At the same time, more guidance is expected from EFSA in the pre-submission phase, possibly speeding up the actual authorization procedure. Given the fact that the new provisions will apply from less than 20 months from now, food businesses may consider speeding up or delaying their application for authorization, depending on their needs.

The Dutch National Probiotic Guide: an innovative alternative for health claims on beneficial bacteria

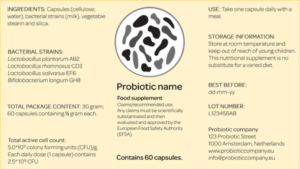

Posted: August 24, 2018 | Author: Jasmin Buijs | Filed under: Authors, Food, Food Supplements, Health claims, Information | Comments Off on The Dutch National Probiotic Guide: an innovative alternative for health claims on beneficial bacteria Probiotics are known as “beneficial bacteria” that can be found in, amongst others, dairy products and food supplements. They are defined by the joint FAO/WHO expert consultation on probiotics as “live microorganisms that, when administrated in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host”. Since the reference to probiotics implies a health benefit, it comes as no surprise that the statement “contains probiotics” in a commercial communication about a food product constitutes a health claim under the Claims Regulation. Moreover, “contains probiotics”, or “prebiotics”, is explicitly taken as an example of a health claim in the guidance on the implementation of Regulation 1924/2006 of the European Commission’s Standing Committee on the Food Chain and Animal Health. At this moment, no health claims for probiotics have been approved by the European Commission. The Dutch Research institute TNO and the world’s first microbe museum Micropia, located in Amsterdam, are nevertheless convinced of the health benefits of probiotics, in particular to protect against antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD). At the beginning of this month, they launched a so-called National Guide on clinically proven probiotics for use during antibiotic treatment in the scientific journal BMC Gastroenterology

Probiotics are known as “beneficial bacteria” that can be found in, amongst others, dairy products and food supplements. They are defined by the joint FAO/WHO expert consultation on probiotics as “live microorganisms that, when administrated in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host”. Since the reference to probiotics implies a health benefit, it comes as no surprise that the statement “contains probiotics” in a commercial communication about a food product constitutes a health claim under the Claims Regulation. Moreover, “contains probiotics”, or “prebiotics”, is explicitly taken as an example of a health claim in the guidance on the implementation of Regulation 1924/2006 of the European Commission’s Standing Committee on the Food Chain and Animal Health. At this moment, no health claims for probiotics have been approved by the European Commission. The Dutch Research institute TNO and the world’s first microbe museum Micropia, located in Amsterdam, are nevertheless convinced of the health benefits of probiotics, in particular to protect against antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD). At the beginning of this month, they launched a so-called National Guide on clinically proven probiotics for use during antibiotic treatment in the scientific journal BMC Gastroenterology

National Guide

The National Guide is presented as a tool for healthcare professionals, patients and other consumers to recommend or use the probiotic products listed as scientifically proven to prevent diarrhea caused by the use of antibiotics. While antibiotics fight bacterial pathogens, they also have a disruptive effect on the body’s own gut bacteria. One in four adults experiences diarrhea caused by ADD. The National Guide promotes probiotics for their function of protecting the gut flora from the disruptive effects of antibiotic treatment, fostering recovery and reducing the risk of recurring infections.

Science-based approach

The research behind the Guide involves a literature study of clinical studies that are all based on randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled trials. Moreover, all of the trials clearly define AAD and have a probiotic administration regime for a period no shorter than the antibiotic therapy. 32 of the 128 initially identified clinical studies were selected in line with the aforementioned criteria. After the selection and review process, available probiotic products on the Dutch market were listed to be subsequently matched with the formulations as proven effective in the selected clinical studies. Only eight probiotic dairy products and food supplements marketed in the Netherlands specified on their label the respective probiotic strain(s) and number of colony-forming units (CFUs) and could therefore be used in the research. The listed probiotic products were awarded with one (lowest) to three (highest) stars for their proven effect as demonstrated in at least one to three clinical studies. The strain Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG with a minimal daily dose of 2 × 109 CFU was found in at least three clinical studies and therefore awarded with a three-star recommendation. This strain was found in 2 products, both of which are food supplements. Several multi-strain formulations resulted in a one-star recommendation; 5 food supplements and 1 dairy product matched such a formulation. The multi-strain formulation Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5 and Bifidobacterium lactis BB-12 was present in two clinical studies and therefore assigned with a two-star recommendation. However, none of the listed probiotic products found on the Dutch market contained this formulation.

Plea for the labeling of probiotics

Plea for the labeling of probiotics

The research is not exhaustive as probiotic products other than the eight that were included in the study might also be effective. However, since this was not communicated on the label, they could not be included in the research. To overcome this gap, TNO and Micropia as the initiators of the National Guide call for the labeling of the probiotic strains and number of CFUs on all probiotic products EU-wide. This could also expand the potential of the Guide. At this moment, strain and CFU labeling of probiotic products is not legally mandatory under the Food Information for Consumer Regulation. The initiators also developed a special probiotic label to address this claimed deficiency. The label is based on the probiotic label used in the US as created by the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP). The labels are in line with the information that should be demonstrated on probiotic labels according to the FAO/WHO 2002 Working Group on Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food.

National Guide to circumvent limitations under the Claims Regulation?

The Claims Regulation applies to health (and nutrition) claims made in commercial communications of foods to end consumers. This may be in the labeling, presentation or advertising of the food. Besides information on or about the product itself, also general advertising and promotional campaigns such as those supported in whole or in part by public authorities fall within the scope of the Regulation. Moreover, since the Innova Vital case, we know that (science-based) communications made to healthcare professionals may also be regulated by the Claims regulation. The rationale thereof is that the healthcare professional can promote or recommend the food product at issue by passing the information on to the patient as end consumer. Only non-commercial communications, such as publications that are shared in a purely scientific context, are excluded from the Regulation.

It must be noted that the National Guide is, unlike health claims, not a commercial communication originating from food business operators. This does, however, not necessarily mean that food business operators are free to use the science-based Guide in their communication with (potential) consumers or even with healthcare professionals without any reservation. The Guide, which not only lists the probiotic formulations that are beneficial for the human gut flora, but even the names of products that contain those formulations, could turn commercial when referred to by a food business. Moreover, when shared in such a context, the claims made in the National Guide may even enter the medical domain due to the preventive function assigned to foods containing probiotics.

Conclusion